SA’s landless blacks: Why does the impasse continue?

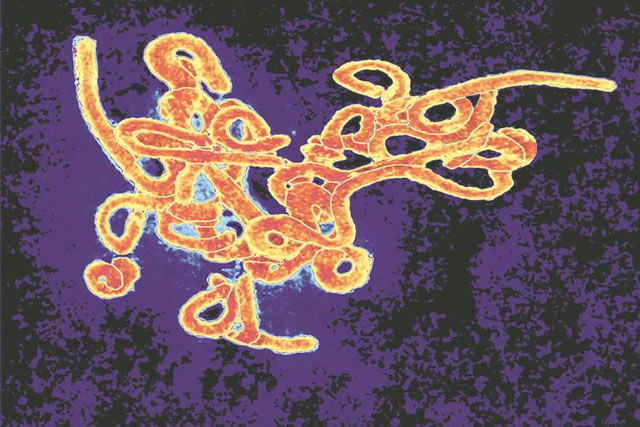

Squatter camps, like the Mandela squatter camp which was in Diepkloof and later moved to Durban Deep near Roodepoort on the West Rand, are clear evidence that South Africa is in need of a land redistribution exercise to right the wrongs of apartheid

Pusch Commey

IT was in 1652 when people of European descent began to systematically drive Africans in South Africa off their resource rich ancestral land, through force of arms, falsification of history, pseudo science, religion, the myth of white superiority and legal skulduggery.Yet for over 1 000 years before the Dutch arrived at the Cape of Good Hope, Africans were already accomplished farmers on their lands. By 1913, the settlers had dug in — deeply. The most brazen act of greed and racial oppression was the Natives Land Act of 1913 which was enacted and enforced by a consolidated white settler regime to deprive nearly 90 percent of blacks of 93 percent of their land. The 7 percent of barren land allocated to them was later increased to 13 percent. It did not end there.

79 percent of the land is still in the possession of white people

The indigenous owners of the land were forced to render neo-slave labour to the new comers for a pittance. But 360 years after the whites landed, not much has changed for the black majority in their quest to land ownership, although in June this year the Restitution of Land Rights Amendment Bill was signed into law by President Jacob Zuma.

The legislation notably reopens the restitution claims process that closed at the end of 1998 and gives claimants five years (up to 30 June 2019) to lodge fresh land claims.

But the devil is in the detail — in the form of the erasure of history, lack of education, lengthy procedures and legal complications, amidst a growing outcry for a permanent and satisfactory resolution of the land issue.

Indeed nothing can sum up the pain, deprivation and suffering South Africans have gone through over the years of both colonialism and apartheid. It is simply immeasurable. But a classic example of the plight of blacks and how they were driven out of their land is poignantly captured by the eminent writer Sol Plaatje, who wrote about the plight of Kgobadi, a black farmer who was summarily evicted from his ancestral land in 1913.

His land was allocated free of charge to a white man, who offered him 30 shillings (about $150 today) to work for him on his former land. Prior to that, Kgobadi had been earning handsomely and been able to feed himself and his family from his surplus crops on the same farm. But when his land was possessed despite his protestations, he was forcibly chased away with his family like vermin. His family never repossessed their land and died in impoverishment.

Neither has the party done something more tangible for the over-70 percent of black people who in 2014 still do not have access to land despite being free from colonial and apartheid oppression. The true and generally accepted realisation is that colonialism, apartheid, racial oppression and factional exploitation, all had an economic motive. And the foundation they were built on was the access to and ownership of land. After all, over 90% of all wars in history have been fought over land and resources. Access to and ownership of land gives impetus to economic resources.

Tellingly, the ANC’s multiracial freedom charter of 1955 called for the redistribution of land. One of its tenets is categorical: “The people shall share in the country’s wealth.” Clearly to have their share, the people need to have access to or own the land.

Yet the compromises that led to the transition to black majority rule in 1994 opted for a different open market approach to land distribution in South Africa, called the Willing Seller/Willing Buyer (WSWB). Effectively the government would simply purchase available land on the open market and redistribute it to landless blacks.

Access to land will empower black people economically

The first Restitution of Land Rights Act was in 1994 and had a deadline for claims until 1998, a period in which black South Africans could lodge claims to their ancestral land. However, it is largely accepted that after 20 years of democracy, the WSWB and the Restitution of Land Rights Act has failed to resolve the historical wrong of land deprivation, for various reasons, including greedy collusions between blacks and whites as well as frustration of the law. A recent land audit found that 79 percent of the land was still in the possession of whites, with government ownership at 14 percent. Some of the ownership of land could not be accounted for.

As illustrated by Kgobadi’s story, the intergenerational suppression of black farming skills and their channelling into cheap pools of unskilled labour to water white prosperity has also meant that prospective black farmers still struggle in the present day.

In addition, self-serving white associations and institutions, including some white political parties, are doing everything in their power to defend their ill-gotten gains.

There has also been the question of what lies beneath the land. Large parcels of land and rights have historically been cornered by white people and housed in their companies. And embedded in them are the natural resources of the country. Then there is other land-related wealth, among other forms, game parks, rivers, flora and fauna, and land for real estate. Within that historical structure is the cheap pool of black labour, encamped in the squalor of squatter camps.

Prior to the transfer of power by the white regime to black democratic rule in 1994, there had been a massive transfer of equity worth millions, in state-run enterprises and government land, to white people — for next to nothing. Many observers conclude this is why white prosperity is no mystery even in the “new” South Africa. Legal challenges within the framework of a neo-liberal constitution have also largely helped to maintain the status quo.

The land trail

In 1996, two years after the end of apartheid, some 60 000 white commercial farmers owned almost 70 percent of land classified as agricultural, and leased a further 19 percent. The ANC pledged to redistribute 30% of white-owned agricultural land to black farmers by 1999, and to return property lost as a result of racist legislation. By 2012, about 8 million hectares had been transferred, which was only about a third of the 24.6 million originally targeted. Only about 80 000 land-restitution claims were lodged by the deadline of 1998 and it is estimated that there are up to five times as many valid cases that can be brought by victims of apartheid-era forced removals.

Moreover, the WSWB open market approach has led to the inflation and over-valuation of lands targeted for redistribution. And an expropriation bill signed into law also makes it possible for government to expropriate land in accordance with the constitution if it is just and equitable to do so.

However, what has recently rattled the hornet’s nest is a draft proposal by the minister of land reform and rural development, Gugile Nkwinti. The draft policy, titled Strengthening Relative Rights of People Working the Land, is an attempt to protect farm workers from eviction, as experienced by Kgobadi, a plight which has continued in various forms, even in a democracy that is guided by the rule of law. The policy proposes a 50 percent equity share scheme for long-term farm dwellers.

The State will pay for the 50 percent portion, but the money will not go to farmers but to a development and investment trust “jointly owned by the parties constituting the new ownership regime”. The document proposes that farm labourers assume ownership of half the land on which they are employed.

The official opposition, the Democratic Alliance (DA) has warned that it will be a recipe for disaster. “It will exacerbate insecurity, destroy jobs, escalate the already catastrophic exodus of farming expertise from the industry, and have dire implications for food security in the medium term,” DA leader Helen Zille told journalists in parliament.

The DA had started experimenting with it in the Western Cape Province where it rules. Zille questioned why the government appeared to have abandoned the NDP model in favour of Nkwinti’s latest proposals. “Why aren’t we giving the NDP model a chance?” she asked. “We will oppose any legislation emerging from the minister’s proposals in their current form,” she said.

When Virgin boss Richard Branson purchased large tracts of land in the Western Cape, the EFF posted him a letter warning him that he was buying stolen property, and that one day the chickens will come home to roost. The EFF has been singing the song of a coming revolution, of black South Africans’ economic emancipation.

In the early 1990s, a diverse group of South Africans sat at a roundtable conference called CODESA, to help resolve the political problems that translated into the nation that is the South Africa of today. As pundits now regularly point out, it could have easily gone the way of Syria, Libya, Egypt or the Iraq of today. But cool and sensible heads ensured that, despite considerable tensions, the country did not descend into the violence and chaos that have befallen these countries.

However, unless the issue of landless blacks is resolved to help empower them economically, there will always be cautious pragmatism about South Africa’s “economic success” because economic inequality is a ticking timebomb.

Pusch Commey is a Barrister of the High Court of South Africa, Award winning writer and associate editor of New African Magazine since 1999. He is based in Johannesburg South Africa. This article is reproduced from NewAfrican.

Comments