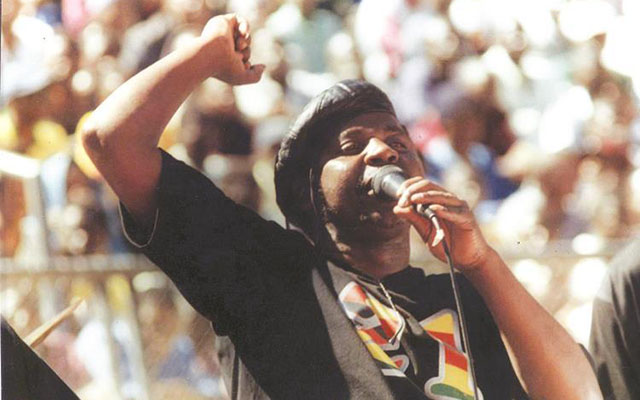

Rodger, Over? A tribute to Cde Chinx

Mhoze Chikowero Correspondent

In March, I spent about four hours in Harare with Cde Chinx together with two of his sons, Chinx was a leading Chimurenga musician and veteran of Zimbabwe’s liberation struggle.I’d spent longer hours previously with the man who addressed me by the name of my great grandfather, Mambo Chiwashira who, like his own great grandfather Mambo Chingaira Makoni, was murdered and decapitated by British colonial forces in the 1890s.

Their heads were delivered to the British queen, and they are still to be returned.

For close to 20 years that I have researched Zimbabwean music, I watched Cde Chinx perform and rehearse, and frequently chatted with him at his house in Chitungwiza, or at places like Liz Bar, a little favourite drinking hole of his along Julius Nyerere Way in H-Town.

We talked about many issues; Cde Chinx was a man of conviction.

He was always jocular, even as he visibly struggled with what he told me was blood cancer, in March.

Two months later, he was hospitalised at the Avenues Clinic.

The images of him bedridden, posted on social media, and when he came out but now incapacitated and wheelchair-bound, were hard to watch.

Has anyone researched the possible “die-forward” effects of Rhodesian biochemical warfare on our liberation fighters and villagers in war zones?

I will have to work with others to fulfil the plans to traverse the guerrilla itineraries through eastern Zimbabwe to Mozambique and Tanzania and back that we had planned in a bid to fully research Zimbabwe’s liberation war history as experienced by the fighters and communities that hosted them, Cde.

It was only yesterday that I watched your recorded “Living Legends” conversation with Masceline Bondamakara, part of her efforts to document brief histories of such great Zimbabweans as yourself. Cde Chingaira, fambai zvakanaka mwana wevhu.

Here is an excerpt of a larger story from my book, African Music, Power and Being in Colonial Zimbabwe, Indiana University Press, 2015, pp.266.

**Explaining his decision to cross into newly-independent Mozambique to become a guerrilla in 1977, Cde Mabhunu Muchapera (interview) credited, inter alia, the freedom songs he listened to on the Voice of Zimbabwe’s Chimurenga Requests programme.

He remembered the songs sung by youths like himself: “Kune Nzira Dzemasoja” (Soldiers’ code of conduct), “Muka, Muka!” (Wake up, wake up!), and a tune punctuated by a rattling AK-47, “Ndiro Gidi” (It is the gun).

Composed by a young female guerrilla, Cde Muchazotida, “Ndiro Gidi” hailed the equalising power of the gun, a tool the colonisers brought to subjugate Africans but which the latter domesticated into a technology of self-liberation.

Each time young Mabhunu Muchapera listened to the militant songs, speeches, didactic dramas, and news updates the programme broadcast, he was overcome with desire to join the action; “Mabhunu Muchapera” is a nom de guerre meaning “Boers, you will surely be wiped out.”

The powerful voices that drew Muchapera and thousands of other youths across the borders also belonged to Cdes Chinx, Murehwa, Sando Muponda, Jack, Mhereyarira MuZimbabwe, Mupasu, George Rutanhire, Max “Esteri” Mapfumo (a former student at Silveira Mission), Vhuu, Serima, and Juliet Xaba, and groups like Zipra’s Light Machine Gun (LMG) and Zanla’s Takawira Choir.

Many youths convinced themselves of the rightness of the cause, crossed into Zambia and Mozambique, and, through song, inspired multitudes to follow suit.

African freedom was now a matter of life or death, the youths sang in such songs as “Somlandela, Somlandela uNkomo, Somlandela Yonke Indawo” (We will follow Nkomo, everywhere he goes) and “Vakomana Vehondo Tinofira Pamwechete” (We will die together as guerrillas) (Dube, interview).

Cde Chinx, who was a great-grandson of a First Chimurenga martyr, Ishe Chingaira Makoni, developed a keen interest in his own troubled history from an early age.

Like other African youngsters, he got the education that mattered from the village dare, the professorial structure that withstood the destructive missionary project [see chapters 1-3], providing a complete reinterpretation of the colonial Rhodesian school accounts that disparaged his ancestor, Chingaira, Nehanda Nyakasikana, Kaguvi Gumboreshumba, Muchecheterwa Chiwashira, and others as “wicked rebels and murderers who were rightly punished for opposing civilisation.”

His account of coming of age conveys the impression that Chinx was a bold young man who took himself very seriously.

Working at a Salisbury engineering firm in the late 1960s, he frequently quarrelled with his employer, one Nichodemus Jacobus Schumann, over the country’s recent history.

“I debated him a lot, standing my ground . . . He would just call people ‘You terrorist, you terrorist!’” Chinx would retort, “You are the terrorist; you came here and colonised us, killing our ancestors. This is our country.”

And Schumann would eventually taunt him into silence: “Go join your fellow terrorists in Mozambique, and come back to fight for your country if you think you can get it back!”

In 1974, Chinx stepped up to the challenge, using a letter of leave that Schumann himself had issued him to go visit his parents in Rusape as his pass to join the guerrillas in the mountains of eastern Zimbabwe.

Writing on the self-legitimating Rhodesian historiography that defined colonial education, Anthony Chennels (2005, 131) observed that Rhodesian history was culled from travel journals like William Charles Baldwin’s African Hunting and Adventure from Natal to the Zambezi (1868), Frederick Selous’ A Hunter’s Wanderings in Africa (1881) and Travel and Adventure in South-East Africa (1893), and subsequent romantic accounts of conquest.

This founding Rhodesian corpus was codified in the journals of Robert Moffat and the Inyati Journals, the Oppenheimer Series, and the Rhodesiana Reprint Library after the Second World War, all these publications helping to constitute a discrete white Rhodesian national identity shaped by its own narratives of heroism and discovery.

Further, as white supremacist notions stiffened in the 1960s–70s, noted Dan Wylie, for a white Rhodesian to “subscribe to [the Rhodesiana Reprint Library felt] like a mild act of patriotism. One could find [therein] unlimited justification for present attitudes” (quoted in Chennels 2005, 132).

These patriotic histories of perceived white invincibility and racial arrogance drove the Rhodesians to take up arms to defend their colonial claim, “Rhodesia the white man’s country,” thus dashing Africans’ expectation of independence at what should have been the “moment of arrival” (Chatterjee 1986, 131).

Like their Zambian and Malawian counterparts, Madzimbabwe had expected independence with the breakup of the Federation in 1963.

In story and song, Africans countered this Rhodesian colonising discourse.

And buoyed by the Communist world’s AK-47, they stood up to challenge colonial certitudes with military force.

Thus, the guerrillas went beyond simply countering the self-justifying imperial Rhodesian history to urge the destruction of the colonial project by armed force.

They outranged the immobilising strictures of the violent state by camping in the pan-African neighbourhood of the independent African states.

From there, they not only attacked, but they also boldly named, taunted, and insulted the enemy in their guerrilla radio broadcasts, songs, and newsletters, engineering a new post-colonial nation-state from exile.

One of Cde Chinx’s first compositions was the blockbuster “Maruza Vapambepfumi” (You have lost the war now, plunderers), which, as he boasted to his mentor, Cde Mhere, he could sing “from Rusape to Harare without repeating a stanza!”

It was simultaneously an elegy to colonialism and a new, ennobling narrative hailing the imminent era of self-determination.

In a double move, the song narrates and celebrates the heroism of African resistance, and similarly narrates and immortalises colonialism as an unforgettably shameful act of European barbarism.

Barney and Mackinlay (2010, 9) note that a counter story, or counter song, contains elements of repudiation, resistance, deconstruction, correction, and redefinition.

In “Maruza Vapambepfumi,” Chinx deconstructs the Rhodesian narrative of a founding white civilisation, pointing out how the colonists, led by spies like Selous (who pretended to be a hunter), deserted their overpopulated and hunger-ravaged Europe and the neo-European slave empire of America to plunder Zimbabwe, the Africans’ land of milk and honey:

Vakauya muZimbabwe

They came into Zimbabwe

Vachibva Bhiriteni

Coming from Britain,

Vachibva kuAmerica

Coming from America,

Vachibva kuFrance

Coming from France,

Vachibva kuGermany

Coming from Germany

Kwavakatandaniswa nenzara

Chased by hunger

Vati nanga-nanga neZimbabwe

They made for Zimbabwe

Havazivi kuti inyika yavatema

But this country belongs to the Blacks

Izere uchi nemukaka

It’s full of honey and milk

Ndezveduka isu vatema

But it’s ours, us Blacks

Vakapinda muZimbabwe vaine gidi

They brought their guns to Zimbabwe

Kekutanga vachiti vanovhima

To hunt, they claimed,

Vodzokera, iko kuri kunyepa

Then go back, the liars!

Through intimidation and dubious treaties, the purported hunters twisted the arms of African leaders and claimed exclusive rights over African lands and minerals, trampling the rights of locals, taxing and enslaving them.

They even spurned the offer of peaceful coexistence, “taxing humans, dogs, chickens, cattle, donkeys, and houses!” So now, through the armed counter-violence of African self-liberation, the colonists were taking their painful lesson.

The comrades were going to hit them hard, driving them all the way back to Britain, sang Cde Chinx.

Chinx deployed the pedagogical tool of orality to “challenge the authority of the [colonising] written word” (Muchemwa 2005, 198). Thanks to the guerrilla movement’s emphasis on history in its intensive political programmes, Chinx was able to reclaim and retell African history from an African perspective to an audience brought up on a starvation diet of white supremacy and fear.

“Maruza Vapambepfumi” belongs to the huge Chimurenga oeuvre that boosted guerrilla recruitment, as Chinx nostalgically recalled in an interview in 2006: “I taught the choir the song during mapungwe and we kept polishing it, hitting it until people went crazy; we then sent it over to Maputo, where every one of my compositions was requested for recording and radio play. And man, what recruitment that song inspired!”

Songs like “Maruza Vapambepfumi” and “Ndiro Gidi” resonated powerfully with Africans both at the war’s front and those listening to the guerrilla radio at home.

They critiqued and put into historical perspective the African predicament as rooted in the original sins of Rhodesia: the “plunder, greed and mendacity” of the settlers that Rhodesian history books extolled as courage, self-sacrifice, and patriotism (Pongweni 1997, 69).

African song traditions are inclusive and participatory. Any member of the musical community can participate in the familiar styles of call and response, the yodelling, makwa clapping, and dance refrains, thereby moulding the song narrative in the performative dariro. Thus, Cde Mhere, who assembled the Takawira Choir with Chinx, added a short preface to the nine-minute song.

He felt that the song’s plot omitted a crucial aspect of the popular understanding of the advent of colonialism and African resistance—Chaminuka’s prophecy.

Chaminuka is believed to have thus prophesied the invasion of the land before he was captured and murdered by the Ndebele in the 19th Century. So, Cde Chinx told me, Cde Mhere sang,

Paivapo nemumwe murume

There was once a man

Zita rake Chaminuka

His name Chaminuka

Waigara muChitungwiza

Who lived in Chitungwiza

Munyika yedu yeZimbabwe

In our country Zimbabwe

Wakataura achiti

He foretold that

Kuchauya vamwe vanhu

There shall come a people

Vachange vasina mabvi

with no knees

Munyika yedu yeZimbabwe.

Into our country Zimbabwe.

Chinx started singing Chimurenga songs as a local mujibha during mapungwe before crossing into Mozambique. He recalled, “I started as a mujibha, right in the mountains of eastern Zimbabwe. I was singing right there . . . when we went to open new bases, raising morari. Such songs as “Sendekera” [Keep pushing; composed by David Kabhachi], I would sing them and keep on embellishing them with my own words, depicting what I would be seeing wherever I patrolled. People liked that so much.” In Mozambique, Chinx’s fame solidified with “Rusununguko MuZimbabwe” (Freedom in Zimbabwe), a composition that used the tune of a Christian hymn, now repurposed to predict the coming not of Jesus but of African freedom, and sooner rather than later. “I was taking those gospel tunes which I used to sing in church with my mother, emptying them of all the words about [the Christian] God and filling them with Chimurenga words.” In this way, the guerrillas domesticated and redeployed the pervasive and often insidious Christian hymn.

Excerpt from Mhoze Chikowero, African Music, Power and Being in Colonial Zimbabwe, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, Nov. 2015, winner of the Kwabena Nketia Book Award for the best book on African music scholarship for the years 2013-2016. Copies of the book are available at the Mbira Centre, Glenara Avenue North, Highlands, Harare. Professor Chikowero is the Director of Research at the Mbira Institute and Associate Professor of African History at the University of California, Santa Barbara. He can be contacted at [email protected].

Comments