Rejecting totems in praise of Jesus

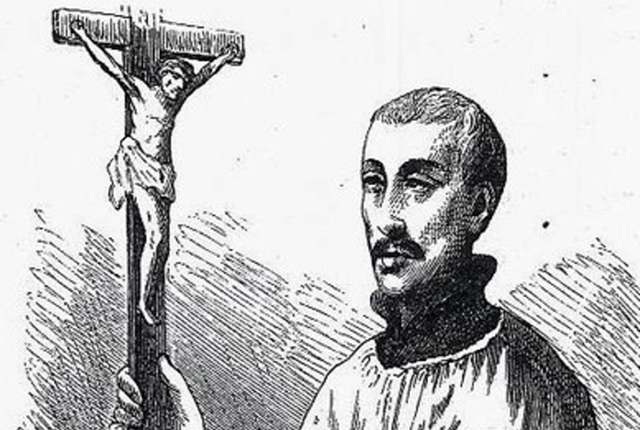

Father Gonzalo da Silveira, a Portuguese Jesuit missionary, arrived at the court of the Munhumutapa around Christmas time in 1556

Sekai Nzenza On Wednesday

“Hatina mutupo. Mutupo wedu ndi Jesu (We have no totem. Our totem is Jesus).” These were the words of my niece’s aunt, Mai Magumbo, when she arrived at our village around 10am on Saturday morning. We had never met her before. But family relationships had forced us to meet for the roora or bride price payment for my niece Varaidzo who lives in the Diaspora.

Varaidzo met a nice guy from Zvimba near Chinhoyi. We had already established that Varaidzo’s new husband was of the Gushungo Tsiwo totem. Growing up in the village, we were taught not to marry a person from the same totem to avoid a kind of miscegenation.

Totems are closely connected to a people’s specific identity, with a unique social, economic, or historical background and past. It is a common uniting factor which binds together individuals, families and clans. Therefore, it is taboo to marry a man or a woman from your totem because in such relationships, chances are your lineage is the same and you may have shared a common ancestor not too far away in history. Avoidance of sexual relationship with a person from your totem also helps stop miscegenation or giving birth to children with disabilities.

Gushungo is the chidawo for the totem. The Gushungo people are found in all parts of the country but many are in Zvimba, Chinhoyi and Makonde in Mashonaland West Province. Tsiwo Gushungo belongs to the main Shumba Gushungo Lion totem. They do not eat lion meat, because it’s taboo to do so.

Since we belong to the VaHera Eland totem, we can marry into any other totem except ours. So, when Mai Magumbo arrived, it was best we clearly established our totems so we knew how to relate to each other.

If she had said her husband belonged to the Nyati or Buffalo totem, then I would have immediately greeted him as my uncle, brother or nephew to my mother who was of the Buffalo totem.

When our new visitors declared that they have no totem except Jesus, there was silence among the elders who had gathered for the lobola ceremony.My cousin Piri broke the silence.

“Shall I show you around the village homestead?” she said. The visitors agreed and Piri took them to the vegetable garden so they could admire rows of ripe tomatoes. My cousin Reuben turned to the three elders around, including Mbuya Gambiza, my mother’s friend who is staying with us, and said, “Mbuya, kana munhu achiti haana mutupo, tomuchingamidza tichiti chii?” How do we greet and welcome a person with no totem?

Mbuya Gambiza said such statements were not new. These days, the people who follow various religious movements want to forget their past lineages.

“Why is that?” Reuben asked.

“Our totems give us identity. If we throw them away, what do we become?”

“Ah, what do we become? Varungu ka,” said Mbuya, meaning we become Europeans.

“But who said Europeans do not have mutupo? They may not mention elands, buffaloes, lions and other animals as totems, but they do not throw away their ancestors like that. They go to the graves of their ancestors to place flowers and make silent prayers. They gather on memorial days to honour the dead who died in various wars,” said Reuben.

Then Reuben told us about the day he attended the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps day or ANZAC on April 25 when he was living in Australia. He accompanied a friend whose great grandfather was a soldier in the Australian army.

This day commemorates all New Zealanders killed in war and also gives honour and respect to those who survived the war and are called returned servicemen and women. This date also recognises the anniversary of the arrival of New Zealand and Australian soldiers on the Gallipoli Peninsula in 1915, during the Ottoman First World War. For eight months, Australia and New Zealand suffered heavy casualties from the Ottoman Turkish soldiers. They lost more than 8 000 Australian soldiers and many Australians and New Zealanders remember their ancestors on April 25 each year. They go to the war memorial at dawn for prayers.

“My friend’s parents even travelled to Gallipoli to collect the soil from there. They came back and held a ceremony at the family cemetery and buried the soil from Gallipoli. So, shall we stand back and say the Westerners do not appreciate ancestors?” Reuben asked.

“When Europeans first came here, we resisted Christianity because it took away our identity,” I added, recalling what history has taught us.

The Roman Catholic missionaries were the first to arrive in Southern Africa.

They penetrated deeper inland and came to Zimbabwe. Father Gonzalo da Silveira, a Portuguese Jesuit missionary, arrived at the court of the Munhumutapa around Christmas time of 1556. He was welcomed at the court of Munhumutapa and met Negomo “who received him warmly”.

Within 25 days, Negomo was baptised by Gonzalo da Silveira together with his mother and many others. But this upset the Muslim traders who feared the spread of Portuguese commercial influence in the Munhumutapa Empire. They accused Gonzalo da Silveira of being a spy and a witch. Negomo believed the Muslim traders’ story and ordered the murder of Gonzalo da Silveira.

A dozen Catholic churches were built after Gonzalo da Silveira’s death. But these had disappeared by 1667. Some years later, Silveira was canonised as a martyr by the Roman Catholic Church. There was no trace of Christianity in the Munhumutapa kingdom until the wave of Protestant missions in the 19th century.

Because there was so much resistance to Christian influence, it took a very long time for the missionaries to return to present day Zimbabwe. In 1879, three Jesuit priests arrived to evangelise Matabeleland. Lobengula received them well and “granted them a free passage through his dominions and allowed them to train his subjects in habits of industry but not to preach the Gospel of Christ which, as he well knew, would lead to drastic changes, not only in the domestic life of his people, but in his whole system of government”. Although the missionaries stayed for a whole 14 years without converting anyone, they helped prepare the ground for the signing of colonial treaties in what was to become Southern Rhodesia.

In a book titled Memories of Mashonaland by B. G. W. H. Knight-Bruce, Bishop of Mashonaland, published in 1895, we get a view of the missionary perception of Africans. He wrote: “When, some nine years ago, I was looking about for some untouched country, Mashonaland, as I wandered in imagination over the country to the north, presented itself . . . The Matabele were then in the heyday of their power; magnificently, one might say almost painfully, arrogant, believing, I think, honestly that there were no people like them in the world . . . Their placid brute courage was very perfect.”

As Christianity continues to spread in Zimbabwe today, we are witnessing little resistance or questioning of what it means to worship and how this affects our history and identity as a people.

When Mai Magumbo came back with Piri, we waited for our in-laws to arrive. The full kuroora or bride price ceremony was done as per tradition, with everyone addressing each other by their totem. Then the groceries from the in laws were placed in front of us. Mbuya Gambiza started the praise poetry of the Gushungo clan, forgetting that such recitation was no longer acceptable to our Christian relatives. Mbuya Gambiza´s clapping and sign of respect were impossible to translate:

Maita Gushungo,

VokwaNzungunhokotoko,

Muchero waNegondo,

Maita Tsiwo,

Vambwerambwetete,

Kugara pasi kusimuka zvinohwira vhu,

Tatenda varidzi venyika,

Vakabva Guruuswa,

Maita vokwaZvimba,

Vomutupo weGushungo,

Vari Chipata naMaringohwe.

Aiwa mwana waZvimba,

Zvaitwa vaNgonya

Many of us now belong to various churches and proudly announce to new relatives that our totem is Jesus. We must wonder and question if we are continuously and perhaps unknowingly being colonised spiritually, as if we have no ancestral past.

This historical past may not be written, but it is well and truly buried in the way we relate to each other by using totems. Surely we can drink wine at Holy Communion and still call each other by totems.

Dr Sekai Nzenza is a writer and cultural critic.

Comments