Recognising cartoon codes

If for example a man is stout and smokes a big, fat cigar, the cartoonist may want to provide an impression powerful politician

Knowledge Mushohwe Correspondent

Editorial cartoons are developed for a newspaper’s general readership and as such, require a minimal amount of skill and knowledge to interpret, or decode them. In order to make their drawings more effective and therefore better understood, cartoonists generally opt for a conventional code, namely symbols.

If a combination of signs or symbols are arranged in such a way that they convey a meaning, they become a visual, signifying code.

Techniques used to unite components of an image to enable them to convey meaning jointly may be described as codes of content.

This is also referred to as the visual mode of the composition in still images.

In editorial cartoons, people, furniture, scenery, buildings, streets or any identifiable object created by the cartoonist and within the composition fall into this category collectively forming the content of the image.

Codes exist only in and through the way people use them.

Editorial cartoonists may use satire for example, but it is only a technique with no physical appearance. They are also culture and context-based.

The use of the colour red brings out so many different meanings across the world, meanings that are not always shared by these communities.

Additionally, codes function intertextually — one can only learn to understand and interpret a code through other codes used elsewhere.

Another character of the code is that it is dynamic — it has the ability to change.

However, some codes have been used repeatedly by cartoonists across the world and their meaning has become universal.

If for example a man is stout and smokes a big, fat cigar, the cartoonist may want to provide an impression powerful politician.

The cartoonist’s use of these symbols is enough to get the message across without words. Similarly, if a character is depicted as small, the cartoonist probably wants to indicate that the character is weak or insignificant.

To understand a cartoon’s message properly, a reader has to identify the codes inherent in it and interpret them correctly.

Cartoonists also use another set of codes, termed rhetorical devices.

These are methods that mix pieces of current affairs to produce a desired comic effect.

Being able to recognise these devices is another useful skill for decoding a cartoon.

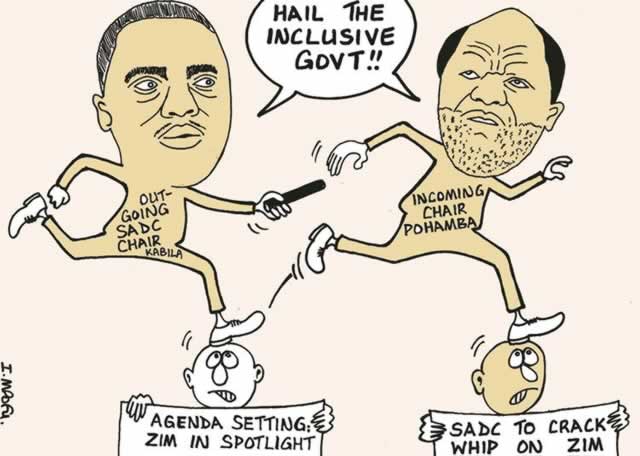

These rhetorical devices include opposition, in which a complex situation is reduced to a struggle between two characters or situations, such as comparing presidential candidates in an election.

Condensation, in which disconnected events are compressed into a common frame, as is the case when political events are likened to a boxing match is another vital rhetoric device employed by cartoonists.

Combination refers to the deliberate juxtaposition of elements or ideas with different meanings, whereas in domestication, a news event is depicted using familiar or even folkloric cultural references.

In other words, determining the type of device at work may help the reader appreciate what is meant by an editorial cartoon.

The work of a cartoonist is based to a large degree on the references of his society and his time.

That is why trying to understand cartoons from the past may seem like trying to read a newspaper from a foreign country — a reader may experience difficulties in understand it if the context is not apparent.

The characters portrayed in a cartoon are often hard to identify, especially if the drawing goes back to a time that a reader may not have had experience of.

Additionally, there may be all the social conventions, such as street lingo, and all the customs of another age that may now been lost.

For example, well before the words ‘bhebhi’, ‘chimoko’ or ‘simbi’ were used in reference to a girl, 1980s folk used the word, ‘chukaz’, one that may mean anything to the young generation of today.

In many cases, a cartoon that made people laugh at one time will not even get a smile out of someone who looks at it with no knowledge of the context, who doesn’t have the cultural references required to read it.

On the other hand, cartoons may regain its relevance when they are put in their historical context.

As commentaries on a specific moment in time, they quickly become dated, but interest in them can be revived by reconstructing the situation in which they were created.

A cartoon is an editorial statement on some aspect of current affairs.

Cartooning requires both creativity and critical judgment on the part of the artist. When a cartoon is put in its historical context, the political leanings of the cartoonist can be determined.

What is the cartoonist’s view of the situation?

What does the drawing tell us about his opinions, beliefs, prejudices?

Even an old cartoon can spark a real debate today between those who find it funny and those who simply find it offensive.

Critical judgment is therefore another quality needed for reading a cartoon.

Comments