Re-framing beauty, power of the short story

Stanely Mushava Literature

TodayBook: Writing Africa in the Short Story

Editor: Ernest N. Emenyonu

Publisher: James Currey (2013)

A fresh stimulus is in the line for the reception of the short story as a wholesome and independent genre. “Writing Africa in the Short Story” comes across as a graphic compendium on African short fiction, invoking the beauty and potency of the genre for full scale appreciation.

The short story has long been sidelined into a peripheral genre, assigned with second fiddle functions as a prelude, footnote or afterthought to the novel. Critics have often diminished the genre into foregrounding template for later exploitation the same way a transient news report is regarded as a first draft of history.

However, multi-pronged efforts have been fermenting over the years to do away with the skewed stratification of genres and secure the celebration of short story as an autonomous social engine.

Artists and an increasing number of midwives have committed to the proliferation of the short story, with lump sum incentives like the Caine Prize for African Writing being dangled to sustain the momentum.

This timely offering from the African Literature Today series swells the hype and escalates critical engagement with the genre. The critical essays do not initiate, but articulate a revolt that is coming full circle, short-circuiting the nominal valuation of the short story and underscoring its peculiar edges.

Ama Ata Aidoo, that grand matriarch of African literature, bemoans the ostracism of the short story, with the qualification of her multi-disciplinary credentials.

She said: “I think the short story is unfortunately rather misrepresented. As somebody who has also worked with that other ‘brief’ genre, poetry, I have found that African scholars and teachers have paid attention only to the novel. This is to be lamented.”

Having dabbled with three novels and three plays as high school set-texts, with no short stories and poems to talk of, I can readily second Aidoo’s concerns on this institutional aversion to the “brief” genres. Teachers and critics have categorised African literature into an Orwellian superstructure where the novel is ostensibly the highest creative form. While short fiction and poetry share the base of the pyramid, the short story is apparently the worst-affected casualty.

Poetry and drama maintain their exclusive domains, but the short story is erroneously subjugated into the apprentice novelist’s lot.

When one considers what the short story is capable of on its own, this presumption can be dully reworked.

Off-hand, I can single out Leo Tolstoy’s short story “What Men Live By” as the greatest literary accomplishment of all time. Against this background, whether ascribed to personal taste or critical conclusion, I find it a methodical fallacy to circumscribe the potency of the short story.

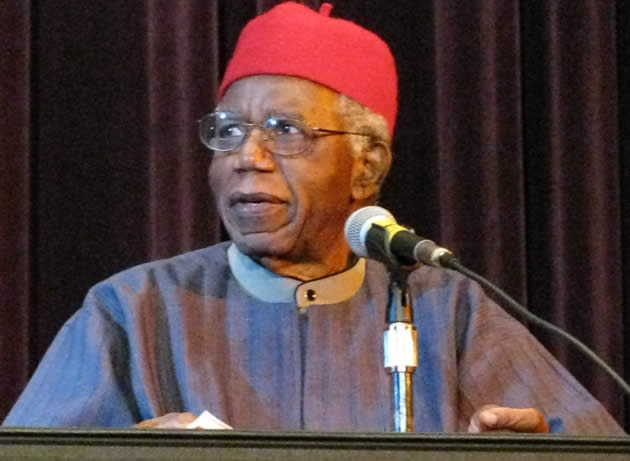

This volume, dedicated to pioneer duo Chinua Achebe, who died on March 21 last year, and Kofi Awoonor, who was killed during the Nairobi’s Westgate Mall shootings on September 21 last year, straddles across the successive generations of the African short story from the trailblazers to emergent phenomena.

Twenty-two years ago, Charles Nnolim lamented: “We all have, up to now, neglected the short story as a genre worthy of critical attention, even though there is already a respectable body of short stories written by our most celebrated writers. Whatever the case may be, our critics must be reminded that the short story as a genre is still stillborn on the African literary scene.

“To deliver this baby, to ensure the healthy birth of the short story (through vigorous response) into the mainstream of the African literary scene is a major challenge facing critics of African literature,” he noted.

Emenyonu reiterates the call, decrying how little has changed in the lapse of the two decades since Nnolim made the observation. At the centre of literature’s social engine function is the ability to capture time while retaining the essence and currency of experience and conversation. While history and kindred disciplines are often framed down to sterile narratives, distilled of life and colour in the quest for certified versions, literature retains for posterity the freshness, novelty and urgency of its snapshots.

Vassily Novikov contends that literature develops with life as a reflection of the writer’s response to the challenges of his time and as a medium of discourse for the future. The short story is a potent instrument in this regard, compensating for its brevity with the benefit of concentration.

The consignment of the genre to a second fiddle domain, therefore, unduly lifts from the critic the burden of engagement with pertinent issues captured through the genre’s peculiar by virtue of the genre’s strengths.

Artists are often averse to the pressure assigning a higher tag on one of their works at the expense of the rest. Achebe argues in his preface to the revised “Arrow of God” that doing so is tantamount to preferring one child above others, which disposition no father worth of his salt will indulge.

Can critics then be justified in paying scant attention to one genre without risking the forfeiture and oblivion of its individual merits?

The combative coterie of critics featured in this volume escalates the fight to abolish the superstructure of genres.

The volume rethinks the African short story as championed by its more accomplished exponents including Aidoo, Charles Mungoshi, Alex La Guma, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and Bessie Head.

The critics engage with the short story to “re-define its own peculiar pedigree, chart its trajectory, critique its present state and examine its creative possibilities. They examine how the short story and the novel complement each other, or exist in contradistinction, within the context of culture and politics, history and public memory, legends, myths and folklore”.

“Real Africa/Which Africa,” Eve Eisenberg’s appraisal of Adichie’s short stories, probes the plausibility of canonising a body of authentic African literature. The assumption of a normative canon is demonstrated in the deification of Achebe as the model writer whose craft has become a master-template for contemporaries.

Adichie’s “Jumping Monkey Hill” relates this quest for critical consensus thus: “They agreed that Dambudzo Marechera was astonishing, that Alan Paton was patronising, that Isak Dinesen was unforgivable . . . The Zimbabwean said Achebe was boring and did nothing with style and the Kenyan said that was sacrilege . . . ”

Tinashe Mushakavanhu, the only featured Zimbabwean critic, celebrates the resilience of the local short story from notables such as Stanley Nyamfukudza, David Mungoshi, Shimmer Chinodya and Yvonne Vera, to relatively new entries such as Brian Chikwava and NoViolet Bulawayo in his entry “Locating a Genre”.

Mushakavanhu, however, decries the prevalence of the story that panders to CNN and BBC frames and lenses.

The decline of literary magazine culture is also lamented as a death-knell to creativity and discourse.

On the whole, “Writing Africa in the Short Story” is a comprehensive range of conversations poised to inject an impetus in the growing fascination with the short story.

Comments