Presidentialism, Parliamentarism, Patronage and Profiteering

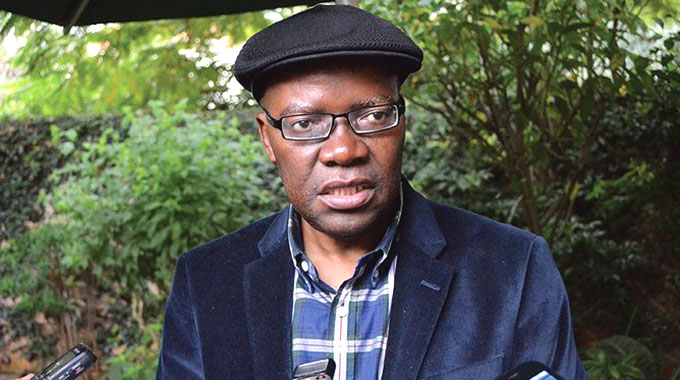

Reason Wafawarova on Thursday

IT is important that the continent’s intellectual community becomes honest and competent enough to make comprehensive analyses of the impact leadership has had in post-colonial Africa. We have seen the rise of both informal and formal politics in Africa, and like in the Chinese Communist Party, where leadership has always been dealt with as an informal structure that is neither explicitly written in the party’s charter nor in any other document, informal power politics have played a central role in shaping the structures of African liberation movements and their respective political parties, as well as in the post-independence political parties.

What is important in African politics is not necessarily the holding of the top formal posts within political parties.

Rather, the most important thing is how close one is to the central leadership — that core team that exercises political power ahead of everyone else. Formal leadership has its many layers that need to be examined, and the predetermining motivation behind formal leadership is the need to appear to be adherents to perceived international standards of democratisation.

We have seen a lot of pretentious posturing disguised as principle in regards to this effort, but surely the intellectual community must not be fooled. The mentality behind the politics of Africa today is that political leaders primarily hold, control and distribute power and resources.

We inherited a colonial legacy where the ruling minority relied on holding, controlling and distributing power and resources with the supremacist aim of marginalising the majority of our masses.

It is now 60 years since we reclaimed our political independence from the colonialists, but our leadership has failed to divorce itself from the deadly effects of this colonial legacy.

As if in betrayal of the Pan-Africanist unity that helped us to destroy the pillars of coloniality, we have our leadership so massively constrained by political and economic instabilities within our own borders.

We can look at how Nigeria is burning now, how South Sudan is fast defining itself in war terms, and we can also take a look back into history in revisiting the murderous Cold War civil wars of Angola, Zaire and Mozambique.

All that can be seen in these conflicts is a continent smitten by the zeal of novices — political leaders who do not look beyond power politics.

We as a nation are not the best example of economic stability at the moment, and there is probably no greater threat to national security than a plummeting economy.

Although things are slowly changing for the better for the African woman, leadership on the continent largely remains neo-patrimonial. There is a masculine tint in the African political culture that comes at the expense of policy depth, and that has significantly contributed to the marginalisation of women in our political processes.

Much to the detriment of the development of democratic institutions, we have seen this ubiquitous entrenchment in the politics of titles, be it presidentialism, parliamentarism or any of the other titles that come with control and distribution of political power.

There is an ominous neglect of developmental politics in favour of clientelism, and we have seen African governments systematically gravitating towards the use of state institutional resources in pursuit of centralisation of power.

Legitimised by the narcissistic doctrine of the founder mentality, or by the legacy of liberation struggles, we have seen the rise of personalised, if not autocratic political power within our political parties across Africa, and needless to say, this trend has often extended itself right into state operations.

Many people have singled out leaders like Jose Dos Santos of Angola, Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo of Equatorial Guinea and our own President Mugabe for unabated criticism over the issue of “stayism”, given that each of them has exceeded three decades at the helm of their respective countries.

What I find lacking in this highly politicised but legitimate criticism is the lack of any meaningful analyses of why these veteran politicians have stayed this long in political leadership.

We have to scrutinise this simplistic deduction that it all has to do with personal greed for power, nothing more, nothing less.

We can start by looking at Zanu-PF in broad terms. The party is a liberation movement with surviving intact relations with its wartime leadership, including, but not limited to President Mugabe.

All the three people in the presidium derive their legitimacy and credentials from the respective roles they played in wartime leadership of both Zanu and Zapu.

Every other person that has been part of the presidium since 1980 has owed their legitimacy to wartime leadership roles, and this must inform us that the reasons for the time President Mugabe has served as the Head of State and Government may not be as personal as his critics would like to quickly proclaim. We have to look at the political culture within Zanu-PF itself, and only then can we distinguish between collective traits and those personal.

There is a political culture in Zanu-PF that rewards, more than anything else, a proven track record in the liberation struggle.

Ousted Didymus Mutasa’s political career is even older than Zanu-PF itself, having been around for 57 years, a good six years before Zanu was formed.

Does the man want to stay longer?

Not only does he want to stay longer, but he is prepared fight his life away so he can get back to extend his stay, even after close to six decades in leadership.

Ousted Joice Mujuru has been part of Zanu-PF for 41 years, and she has faced disastrous political calamities of late, losing her 10-year-old VP post in a rather unceremonious manner.

Does she think she has played her part for both the party and the country? Well, she has not come out in the open about her future plans, save to say she has indicated that she “will die Zanu-PF”.

Even the often-hailed Nathan Shamuyarira did not relinquish political power at party level right to his death, although he made history by announcing retirement from serving the nation at Government level in the mid-1990s.

Before drawing any conclusions on Zanu-PF, we have to take a look at the political culture in post-independence opposition parties, the often wrongly named “pro-democracy movements,” together with their allies in the civic sector.

Morgan Tsvangirai cannot denounce “stayism” without making a huge fool of himself, and the same applies to Welshman Ncube, and even Lovemore Madhuku.

The MDC was formed in 1999 and Tsvangirai has clung to whatever is left of the party as the leader for 16 years now, and like the “long staying African leaders’’ he would love so much to criticise, his lame explanation has always been “the people still want me there.”

The “MDC people” love Tsvangirai so much that they have not only violated their own constitution to get him to stay on, but they have also endowed him with supreme powers to appoint 36 out of 54 members of his party’s National Executive Council, the equivalent of Zanu-PF’s Central Committee.

The man he loves to vilify across the divide appoints only 10 of the 300-member Zanu-PF Central Committee, from which he also appoints about 25 members to the party’s Politburo.

So obsessed with presidentialism is Tsvangirai that he gets his subordinates to address him as “president Tsvangirai,” even at a time the nation had awarded him with a legitimate Prime Minister position.

Welshman Ncube’s 10 years as the leader of the breakaway MDC formation will be up this year, and the man has a brilliant plan to stay in his position. He will simply coin something called a coalition with the other breakaway MDC formation led by Tendai Biti and Sekai Holland.

So Bingo! Welsh can claim a new political set up and extend his leadership beyond the mandated 10 years. After all that is what Nelson Chamisa told us in 2009 when Tsvangirai faced the 10-year limit inconvenience, and people were asking questions.

Chamisa reminded us that the MDC had only been formed in 2006, since the old party had ceased to exist in August 2005 when the party split into two.

Essentially the spirit of “stayism” is part of the DNA of African politics, and clearly founder members of organisation will often always have what they believe to be a legitimate sense of entitlement, if not ownership of the organisations they lead.

We have to break this unhealthy link between Presidentialism and Parliamentarism to patronage and profiteering, and that way the future of African politics can only get better.

Zimbabwe we are one and together we will overcome. It is homeland or death!

REASON WAFAWAROVA is a political writer based in SYDNEY, Australia.

Comments