PRESERVING INDIGENOUS KNOWLEDGE SYSTEMS

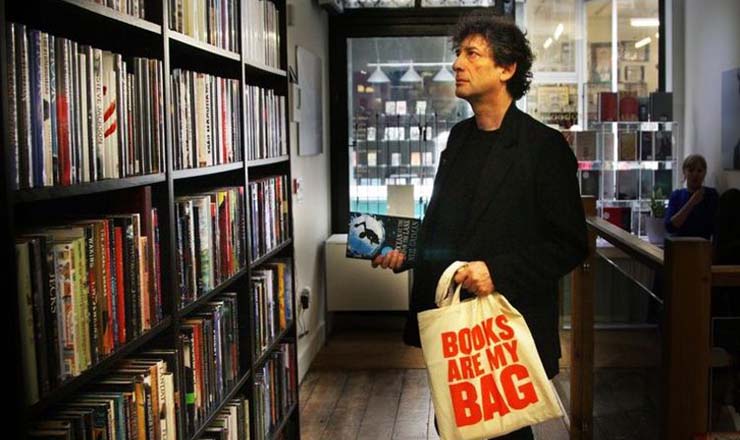

Researchers recommend that libraries can make use of indigenous knowledge experts, such as traditioal healers (above) and village elders to engage in talk shows as a way of getting and acquiring indigenous knowledge from the knowledge holders. Libraries (below) can then acquire the materials and ensure that they are available as part of their collections

Librarians play a significant role in the acquisition, preservation and dissemination of indigenous knowledge (IK). However, in order to execute this more efficiently, there is need for a coordinated approach of IK management at a national level among Government authorities, IK holders, collecting institutions, researchers, and libraries.Working together would enable the establishment of a database which is usable by people with limited experience of computers. The database would provide access to different types of users governed by different access rights to ensure that community engagement programmes are carried out.

Authors Josiline Chigwada and Blessing Chiparausha, both librarians from Bindura University of Science and Education, in their recent presentation recommended the formation and/or resuscitation of the Zimbabwe Resource Centre for Indigenous Knowledge, so that it can work with Government in acquiring, preserving and disseminating IK.

Librarians should also be continuously trained so that they are able to identify, acquire, preserve and disseminate IK in this digital era, the two authors recommend.

Since indigenous knowledge is communally owned sometimes, an online database for Zimbabwe showcasing the different IK that is available can help to disseminate the knowledge, Chigwada and Chiparausha suggest.

Indigenous knowledge is regarded as local knowledge of a particular culture or society, which is in danger of becoming extinct. Indigenous knowledge exist as stories, songs, folklore, proverbs, cultural values, norms, beliefs, rituals, local languages and agricultural practices.

Chemhuru and Masaka (2010) added that taboos, myths and legends such as totems are used to prohibit and restrict some activities which can be detrimental to society.

Chisita and Mugwisi (2011) state that there are more than 25 totems that can be identified in Zimbabwe and taboos and totems help to nurture sustainable use of natural resources.

Indigenous knowledge is regarded as undocumented tacit knowledge that exists in the minds of community people which is passed from one generation to the other by word of mouth (Ebijuwa, 2015).

Adeniyi (2013) notes that African indigenous knowledge is poorly managed and some ideas vanish once the custodians die. In light of the above, libraries can act as repositories of indigenous knowledge to ensure that it is accessible and usable in enhancing sustainable development in a country. It is another rich source of reading materials in different sectors including schools, communities and government institutions.

The two authors conducted a literature review to establish what libraries are doing as repositories of indigenous knowledge and what was being implemented in Zimbabwe.

Forty-two librarians in selected libraries including special, public, school, and academic libraries were interviewed in an attempt to establish whether their collection includes indigenous knowledge.

Chigwada and Chiparausha’s findings indicate that indigenous knowledge is mainly preserved in school and public libraries in the form of poetry, folklore and drama; special libraries in the arts and culture sector display and exhibit artefacts and live demonstrations of traditional dances and recorded live sessions on compact disks and digital versatile disks; while academic libraries have print and electronic information resources on indigenous knowledge.

They argue that libraries are best suited to house indigenous knowledge since the information professionals and librarians are well-versed in the process of acquiring, preserving and disseminating any kind of information resource.

It was also discovered that librarians have the capacity to tap the knowledge from the holders of indigenous knowledge so that it can be accessible.

The authors recommend that librarians and information professionals should be incorporated when dealing with the preservation of indigenous knowledge since they play a major role in ensuring that the existence of the knowledge is safeguarded.

The two authors submit that indigenous knowledge has a role to play in the implementation of sustainable development goals (SDGs) in developing countries.

They cite that the International Federation of Library Associations recommends that libraries should collect, preserve and disseminate indigenous knowledge as a way of showcasing its value and importance. In the process, there is need to recognise intellectual property to ensure that indigenous knowledge is protected in order to encourage the knowledge holders to contribute towards the development of indigenous knowledge repositories.

Libraries in Zimbabwe range from school, academic, special, public, community and national libraries.

Libraries help in facilitating access to indigenous knowledge by acquiring IK, preserving it and then organising it for dissemination.

All the types of libraries have a mandate to house indigenous knowledge collections that depict what is done around the community where the library is located. The public library, for example, is regarded as a local centre which provides access to all kinds of knowledge and information according to the UNESCO Public Library Manifesto (1994).

In terms of academic libraries, former South African president Thabo Mbeki (2005) states that higher education has a role to play in the economic, social, cultural and political renaissance of Africa and in the drive for the development of Indigenous Knowledge systems.

As a result, academic libraries should be reorienting their services to meet the needs of the indigenous people.

Training institutions, the authors found, are also offering indigenous knowledge systems as a course to strengthen the capacity of librarians on issues that pertain to the management of IK. For example, at the National University of Science and Technology, the course is offered at post-graduate diploma and master’s degree levels.

Acquisition of

indigenous knowledge

Okore (2009) recommends that libraries can make use of indigenous knowledge experts and village elders to engage in talk shows as a way of getting and acquiring indigenous knowledge from the knowledge holders.

In public and school libraries for example, storytelling sessions can be held whereby elders and experts are invited for storytelling, audio and videotaping. This can be accomplished when libraries identify potential sources of indigenous knowledge and then tap the knowledge from these people to ensure that it is accessible.

Librarians can also go into the field and interview indigenous knowledge holders and then with the holders’ consent, record them on audio or video tape while they are explaining their knowledge, beliefs and practices.

Indigenous knowledge practitioners can also be encouraged to write books on practices within their communities (Ramanan, 2015).

This is done to ensure that indigenous knowledge holders independently record their own IK in the context of their unique knowledge systems.

But also, librarians and writers can partner to provide training sessions on how IK holders can undertake this exercise. This would help in retaining confidence in terms of ownership and can encourage the holders to contribute their knowledge.

Libraries can then acquire the materials and ensure that they are available as part of their collections.

Researchers should also be encouraged to research on indigenous knowledge of various communities to ensure that IK is documented and made retrievable when needed.

Acquisition of indigenous knowledge can also be conducted through attendance of social events involving intangible cultural heritage and practices to record peculiar parts and entities on digital devices.

Some IK holders also want to keep what they know for fear of losing their intellectual property rights. As a result, there is need to enlighten and assist IK holders on intellectual property issues so that they can patent their property and thus avoid losing it.

Preservation of

indigenous knowledge

Libraries can create institutional repositories where acquired IK can be preserved. Okore (2009) argues that librarians are not owners of IK but custodians who can dialogue with community members through the social spaces. As a result, libraries should promote community publishing so that communities document their own IK, for example, the Ulwazi project in Durban, South Africa, whereby people in the community contribute in the population of the database.

In Murehwa, for example, there is the Murehwa Culture Centre, which was established to tap into the IK of the surrounding communities. Academic libraries have a mandate of preserving the research output of the institution. Librarians should collaborate with researchers in higher and tertiary institutions in conducting research in IK and then deposit the research output in institutional repositories to preserve it.

Dissemination of

indigenous knowledge

Libraries have a role to play in facilitating the dissemination of indigenous knowledge. The establishment of digital libraries of indigenous knowledge would encourage researchers to study and improve the indigenous knowledge. This would also guarantee the existence of such valuable and unique facets of local communities.

Web portals would increase the visibility and access to endangered elements of cultural heritage. — Panorama.

Comments