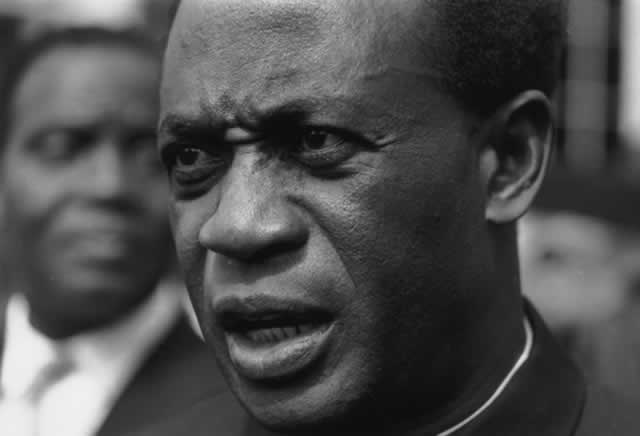

Nkrumah: The man in a hurry?

Stanely Mushava Literature Today

The failure of Nkrumah’s vision for unification and empowerment during his own time does not suggest that these ideals were a blind alley.

Kwame Nkrumah is perhaps the closest personification of pan-Africanism.

A charismatic statesman and prolific philosopher, his name is often invoked like a letterhead in most discussions on African unity and black empowerment.

As Africa turns in affectionate hindsight to its formative ideals, Nkrumah continues to command respect for his vision and labour of love for Africa.

His credentials as a revolutionary effigy are secure.

He is an ideological mainstay for a continent long in travail, coming to terms with the need for unity and economic self-determination, ideals curtailed by leaders who lack the political will to navigate the course from rhetoric to reality.

With a climate of discontent defining the politics of the day, the mood is current to situate pan-Africanist icons, eminently Nkrumah, in romanticised retrospect and deploy their ideas as a blueprint for the continent’s dream dispensation.

Amilcar Cabral said, in moving homage to the great leader: “Nobody can tell us that Nkrumah died of a cancer of the throat or some other ailment. No, Nkrumah was killed by the cancer of betrayal.”

The assertion stands up in light of the ordeal meted on Nkrumah by his presidential contemporaries who were brazenly opposed to his vision for a united Africa, erroneously assessing it in terms of Nkrumah’s personal ambition instead of a valid African cause.

“For us, the best homage we Africans can render to the immortal memory of Kwame Nkrumah is to strengthen vigilance at all levels of the struggle, to intensify it, and to liberate the whole of Africa,” Cabral said.

At a time when Africa remains the surrogate of Western capital, benefiting less than 10 percent the value of its resources, Nkrumah is vindicated.

It is once again fashionable to abstract his name as an inspirational emblem towards the maximisation of Africa’s interests.

However, biographer David Rooney urges us to slow down and make a few considerations.

Having given it up to Nkrumah as a matchless champion of the African cause, Rooney cautions in his book, “Kwame Nkrumah: Vision and Tragedy”, that the veneration of Nkrumah as a faultless visionary is a potent source of problems.

Nkrumah, for all his visionary radiance, also made costly mistakes.

If his memory is to reward the continent, then we must reroute from oversimplication of his legacy to a more objective assessment.

Relevant lessons for our day are to be gleaned neither by his deification in juxtaposition with Western capital nor by his demonisation in juxtaposition with normative statecraft.

They are to be gleaned by humanising him; approaching him as a flawed mortal who had prodigious aspirations but also made grave mistakes.

“Nkrumah will be seen as a man of vision whose achievements were undermined by the inadequacy of his administration,” Rooney points out in the introduction to his biography.

Rooney captures Nkrumah’s vision to three principal components, chiefly, the total liberation and unity of Africa and its non-alignment to superpowers; economic transformation, not merely in terms of growth but in sustained and autonomous development of both society and the economy; and national unity, taking precedence over regionalism and ethnocentrism.

This is, without controversy, the course Africa must take and is need to summon our will and take another go at the total attainment of these ideals.

Wisdom is vindicated by her children and every statesman and scholar of pan-Africanist orientation gives it up to Nkrumah for his able propagation of these ideals.

Most works directed at chanting down imperialist capital acknowledge Nkrumah’s special place, as did liberation movements at home and the civil rights movement in the African Diaspora.

Rooney also acknowledges this but goes on to take the less travelled thoroughfare.

Instead of overlooking the less palatable aspects, as the case is in the posthumous euphoria for the exceptional leader, Rooney underscores them, arguing that they must be considered well so as not to be repeated.

An approach of this kind is significant in that Nkrumah’s administration is a pilot project in the quest for the grand design for Africa.

His successes are therefore as important as his failures.

Mistakes are perhaps the most expensive segment of history. Making them is inevitable but wasting them is inexcusable.

For those who do, retribution is sure.

The failure of Nkrumah’s vision for unification and empowerment during his own time does not suggest that these ideals were a blind alley.

Rather, that they are lessons to be utilised from his troubled tenure.

One simplistic approach is to exclusively blame external meddlers.

There is proof which cannot be gainsaid to this end but it is naïve, even self-deprecating, to suggest that Africa is wholly remote-controlled by Western imperialists and to deny domestic agency in the interaction of Africa’s promises and perils.

As Africa leaders merit credit for their accomplishments, they must also admit censure for their mistakes.

We must expunge the black hole by which leaders are allowed to outsource accountability thereby allowing a free course and indefinite cycle for their mistakes.

This is part of Rooney’s motivation in humanising the legend.

His biography draws from a voluminous range, people who knew Nkrumah personally and hitherto inaccessible files.

Dispatching his homage for the pan-Africanist icon, an Africa-American academic, calls Nkrumah “the Black Caesar”.

An interesting comparison given the towering importance, unwitting vulnerability and ultimate tragedy shared by the icons.

For Rooney, the trouble with Nkrumah was that he was given to urgency.

Lack of capacity for execution rendered his intellectual exuberance a file too large to retrieve.

“Nkrumah, always a man in a hurry, allowed haste to dominate his judgments,” Rooney says.

Rooney notes that Nkrumah’s contribution to the failure of his own vision of scientific socialism was indifference to pragmatic administration.

Nkrumah, says Rooney, “conjured up one brilliant scheme after another” but had “neither the ability nor the patience to think through all the implications of cost, staffing and commercial viability”.

Indifference to financial issues and refusal to demand honest accounting which opened the “floodgates to corruption on every level”, a vice he ironically tolerated, were the undoing of his vision.

Nkrumah was also intolerant and was increasingly tyrannical in the lead-up to his deposition.

This cost him the sympathy of those who counted his a progressive third world leader.

His construction of a $10 million prestige project, Jobs 600, to house the OAU at a time when his people were desperately queueing for food, sent a wrong message about his priorities.

He was perceived as basking in the fanfare of the world stage instead of taking advantage of his country’s rich resource base to maximise the welfare of his people.

The death of a longtime political rival in prison, the dismissal of his Chief Justice for passing a verdict which he did not like and subversion, with the help of Eastern power blocs, of countries opposed to his agenda in the OAU, lost him strategic support at home and abroad.

Noted pan-Africanist writer CLR James, among those shocked by the new climate of terror:

“Perhaps Nkrumah’s greatest weakness, and the greatest warning to his successors, is that although he had a brilliant vision, many of his fantasies bore little relation to stern reality,” Rooney points out.

“While he preached endlessly about the evils of neo-colonialism and exploitation, he presided over one of the greatest swindlers’ bonanzas the world has ever seen.

“He became renowned as a soft touch by sharp businessmen, ne’er-do-wells, and by crooks and diamond smugglers…

“While he preached about socialism, his corrupt minions sold Ghana’s future to greedy flocks of entrepreneurs, and every wasted pound was largely paid for by the sweat of the overburdened cocoa farmer.”

While Nkrumah’s legacy will always be of a visionary who was ahead of his time, uncompromising in his quest for the African unity and generous in his sacrifices for the liberation of African states, his darker attributes are also pertinent lessons for today’s leaders.

Comments