Nexus between poverty, child nutrition

Roselyn Sachiti Features Editor

Vimbai Nyandoro (19) is an HIV positive unemployed mother of two, Ngoni aged three and Zvikomborero (nine months). Her husband Tapiwa (46) is also HIV positive and a follower of the Johane Marange apostolic sect. Church doctrine does not permit them to access health facilities for treatment of diseases, modern contraception, pre-natal and post-natal care, so when Vimbai gave birth to both her children, senior women from their church helped her deliver at home.

Because of the home delivery, she missed out on the prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV programme offered by Government and its partners.

Her children do not also go to the local clinic for weighing.

In the Chadereka area of Muzarabani in Zimbabwe’s Mashonaland Central Province where the couple stays, Tapiwa ekes out a living through making tins, dust pans and baking tins for resale in Bindura and sometimes he travels as far as Harare.

Depending on sales, he sometimes makes $60 in a good month, money that is never enough to cater for all the family’s needs.

The $60 is split tactically.

About $30 is used to buy household groceries that include 3kgs sugar, 2 litres of cooking oil, 5kgs flour, 500g tea leaves, 1kg kapenta, salt and 4kgs rice, bath and laundry soaps.

The grocery list also includes an assortment of snacks and sweets that include, Zapnax, Jumbo, Stumbo, bought cheaply in large quantities for the two children.

Since they have harvested eight bags of maize from their small field, they use about $3 per month to pay the miller at their local grinding mill.

The remainder of the money goes towards Tapiwa’s transport fare when he travels to Bindura or to Harare to sale his wares.

As such, their meals from breakfast, lunch to supper consist mainly of starches and junk foods.

If they skip lunch and eat the snacks, their maize meal will last longer.

This has somewhat worked perfectly for them.

Vimbai has developed a routine she religiously follows each day.

First thing each morning, she prepares porridge for her two children, which she sometimes add sugar and salt to give the first meal of the day a better taste.

Afternoon meals, if prepared, comprise sadza and fried or boiled green leafy vegetables and it is the same for dinner.

Ngoni, Vimbai confesses, has eaten fruit only once since he was born, as this can be expensive for her.

In fact, he loves Zapnax or “mazeppie” as she calls them and biscuits and sweets she gives him whenever he complains of hungry.

She, too, does not eat fruit that often, only the God sent wild fruit like masau (ziziphus mauritiana).

For them, masau is like manna from heaven as they harvest the wild fruit from the forest at no cost when in season.

One banana costs 20c, an apple 25c, one orange between 20 and 25c depending on the size, while sweets like stumbo cost 10c each, and snacks like Zapnacks and Jumbo cost 10c per packet.

A packet of loose biscuits can ask for as little as 50c depending on the brand.

When she does not have money, Vimbai gets the sweets, biscuits and snacks on credit from a neighbour who vends at the nearby school.

“I cannot afford fruit which is scarce here and sometimes I just give them (children) ‘ma zappie’,” said Vimbai. “But every morning, I make sure they eat a lot of porridge and also sometimes feed them sadza or samp for lunch.

“I am also feeding Zvikomborero the same food because my breast milk is no longer adequate for her any more. The situation was worse last season because of the drought. Zvikomborero cried all the time and I believe it was because of hunger.”

For four years, Vimbai seemed oblivious that Ngoni looked quite smaller than other children his age.

She says like his late paternal grandfather Sekuru Nyandoro, Ngoni has a small body frame, further describing her son as a “ndonda” (weak person).

Just recently, Ngoni developed pneumonia and Vimbai travelled to her sister’s home in Hatcliffe, Harare, to seek medical help, far away from the prying eyes of other church members.

Where they live, gossip travels like a veld fire and can be too hot to handle, so when she left, Vimbai said she was going to nurse her ailing sister’s husband.

This at least would starve the rumour mill and also save their relationship with their church.

“In Harare, my sister accompanied me to a clinic and nurses said Ngoni was malnourished and stunted,” said Vimbai. “They also performed an HIV test which came out positive. Zviko is also positive.”

When she returns home sometime next week, Vimbai will stop going to church and take her children to the local hospital so that they access paediatric ART and also start feeding them a balanced diet.

“I am not prepared to lose any of my children,” said Vimbai, who dropped out of school after writing Grade 7 final examinations.

“I will look for a job as a maid so that I also earn money and be able to feed my kids a proper diet.

“If my husband wants to remain in his church, he can do so. My children are both HIV positive and stunted. What have I done wrong? I pray every day, why is God punishing me?”

Malnutrition is the lack of proper nutrition, caused by not having enough food or not eating enough food containing substances necessary for growth and health.

Poor feeding practices are a concern in many low and middle income countries like Zimbabwe where malnutrition is a public health concern.

In Zimbabwe, children, especially under fives, both HIV positive and those negative are affected by malnutrition and stunting.

Statistics suggest a higher burden of malnutrition among children in rural communities than in urban areas.

This is a result of poverty rates which are highest among the rural areas and the same applies to food security.

However, intra-urban poverty exists with some urban communities having very high poverty and food insecurity.

Responding to questions sent by The Herald, Director Family Health in the Ministry of Health and Child Care Dr Bernard Madzima said in Zimbabwe, nutrition is an underlying issue in terms of morbidity and mortality in children under five.

“While causes of death mainly are pneumonia, diarrhoea, newborn, HIV and malaria, the nutritional issues become important as those with these conditions become susceptible to malnutrition as well,” he said. “So, it’s cross cutting.”

Dr Madzima said stunting is a form of malnutrition which then results in the individual suffering from physical and mental growth retardation.

“In the last MICS of 2014, stunting was measured at 27,6 percent,” he said. “This is a very high number which means one in four of our children will suffer some form of decreased mental capacity in their adult life.”

Dr Madzima said under nutrition affects a child’s development and IQ to a very large extent.

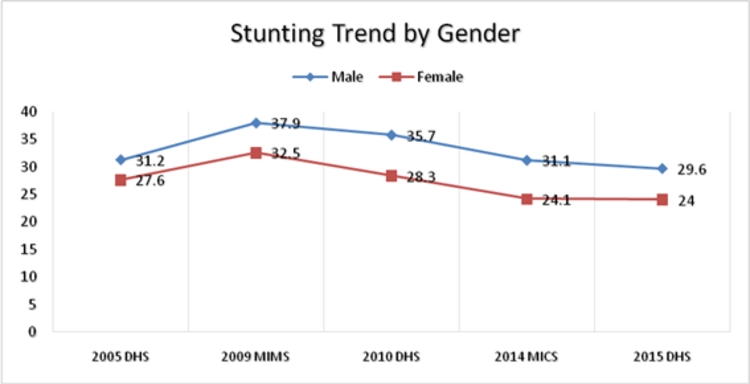

According to Dr Madzima, 30 percent of boys in Zimbabwe are stunted, while 24 percent girls face the same challenge.

He said 22 percent urban children were stunted, with 29 percent of rural children also stunted.

Dr Madzima said child under nutrition and under-five mortality were closely correlated.

“Malnutrition is at the background or is the underlying factor in child mortality,” he said.

Dr Madzima said after six months, a child can have breast milk with appropriate complementary feeding, with right proportions of carbohydrates, proteins, fats and micro-nutrients.

United Nations Children’s Fund Nutrition manager, Dr Ismael Teta, said in Zimbabwe, determinants of malnutrition were varied and generally revolve around health and socio-economic factors.

“This includes a health status (particularly HIV status), family’s socio-economic status, food security and dietary diversity; and other factors such as the mother’s age, level of education, religious beliefs, number of young children in the household, etc,” said Dr Teta.

He said malnutrition implied both under-nutrition and over-nutrition.

“Traditionally, the most prevalent problem has been of under-nutrition and thus malnutrition became synonymous with under-nutrition in the African context,” he said. “Malnutrition can be acute (classified as wasting or underweight) or chronic (termed stunting).”

According to the 2015 ZDHS, stunting is at 26,8 percent. It is essential to note that the burden of stunting is different between boys and girls.

Dr Teta said a compromised nutrition status, especially during the first two years of life caused irreversible damage and had been associated with early onset of metabolic syndromes (eg obesity, diabetes and hypertension).

“During the first two years of life, the child’s body is still undergoing cellular programming, i.e. the body is still learning and teaching itself how to process and utilise available resources (nutrients) and deficiencies during this early stage results in some undesirable metabolic characteristics that lead to early onset of the prior mentioned metabolic conditions,” said Dr Teta.

In Zimbabwe, young children below the age of five are the ones most affected by malnutrition.

These children mainly start to suffer at the age of six months when other foods begin to be introduced.

“Most of the foods used in complementary feeding are mainly starch in nature and do not provide much in terms of other nutrients,” said Dr Teta. “Therefore, the young children are most affected as they wholly depend on the caregivers unlike the slightly older children who sometimes can serve and feed themselves.”

Dr Teta said with respect to wasting and underweight, there was very little difference between boys and girls.

“However, in terms of stunting, boys have a very significantly higher burden compared to girls and little is known as to why this exists in the country,” he said.

“However, this is one of the key research questions expected to be answered by a proposed research into determinants of malnutrition in the country.”

Dr Teta concurred with Dr Madzima that children from rural communities were more susceptible to malnutrition than their urban counterparts.

“Poverty rates are highest among the rural areas and the same applies to food security,” he said. “However, intra-urban poverty exists with some urban communities having very high poverty and food insecurity.

“Analysis traditionally generalised the comparison between urban and rural, without making comparisons within these two groups to identify the most affected communities.”

Dr Teta said almost half the deaths of children under the age of five in Africa had been attributed to malnutrition.

“Poor nutrition has become a major killer, more than malaria and HIV,” he said. “Malnutrition is often inherited from poor maternal nutrition both prior to and during pregnancy, leading to low birth weight infants (9,5 percent according to 2015 ZDHS),” he said.

Nutrition programmes in Zimbabwe are being funded by DFID, as part of its efforts to support in the humanitarian response to the 2015-2016 El-Nino induced drought which resulted in up to 6,189 children between 6-59 months being treated for severe malnutrition in the most affected 20 districts, which recorded high global acute malnutrition levels of five percent and above.

Through funding from the United Kingdom’s Department for International Development (DFID), which has so far contributed the most to the emergency response, UNICEF has been able to provide life-saving nutrition treatment and preventive care to affected populations living in 10 of the 20 districts most affected by the drought.

Over $9 million contribution from DFID will go towards critical life-saving nutrition and WASH interventions, and preventive care to vulnerable children and women.

There is, therefore, need for proper nutrition so that children like Zvikomborero enjoy their first 1 000 days of life.

Feedback – [email protected] or [email protected]

Twitter @RoselyneSachiti.

Comments