Mbira masters and Rhodie gatekeepers

Stanely Mushava Literature Today

Zimbabwe’s mbira sound is spiritual tender in world music. The mbira, perhaps the Southern African country’s flagship culture export, is a defining influence on the country’s hit parade, spiritual landscape and social memory. Zimbabwean musicians who have made international headway, particularly Oliver Mtukudzi, Thomas Mapfumo, Chiwoniso Maraire,

The Bhundu Boys and Four Brothers, have ridden on the mbira sound, live or reimagined in jit riffs.

Lately, biographers, historians and journalists have been building a rich ethnomusicology trove from the country’s foremost mbira repertoire.

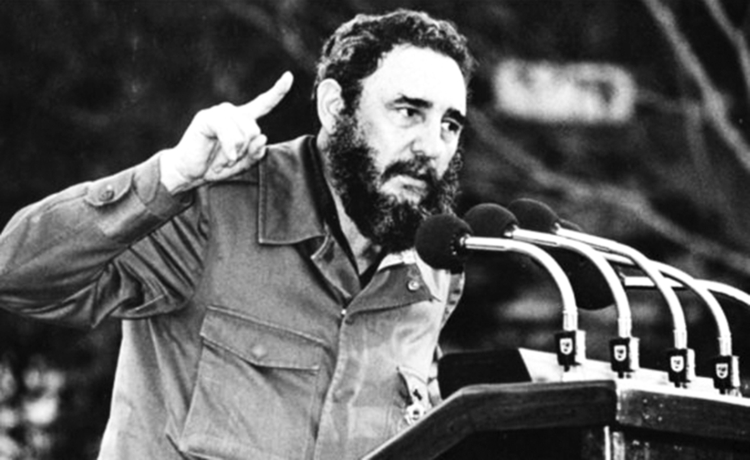

Mapfumo, the Chimurenga artiste whose music became the default soundtrack of the liberation struggle, spearheaded a mbira renaissance, and chanted down barriers to equality in both Rhodesia and Zimbabwe, is a recurring interest in these books.

On November 11, the Society for Ethnomusicology Stanely Mushava Literature Today

(SEM) gave a nod to these efforts by jointly awarding the Kwabena Nketia Book Prize for 2016 to Mhoze Chikowero for “African Music, Power, and Being in Colonial Zimbabwe” (Indiana University Press, 2015) and Banning Eyre for “Lion Songs: Thomas Mapfumo and the Songs that Made Zimbabwe” (Duke University Press, 2015). Announcing the prizes at the annual SEM meeting in Washington DC, ethnomusicologist Jean Kidula noted that both books are “compelling historical works on the working of music in Zimbabwe’s contemporary national and social politics”.

The panel’s choices for the best ethnomusicology titles not only converge on the subject of Zimbabwean music. Both books were conceived outside the discipline of ethnomusicology. Chikowero is a historian and Eyre is a biographer.

The writers, who have previously collaborated course around their vast spans of research with freewheeling lyrical facility and a confessional attachment to the world of the Shona.

Kidula said Eyre’s book cast the spell of an unputdownable novel on his crew. “Banning’s writing is engaging and poetic, carefully utilising storytelling, biographies and detailed descriptions as well as analyses of sonic and extrasonic elements.”

Although Mbira Month was a low-key affair, barely mentioned outside official arrangements, with citizens carried along by new waves of urban culture, what Zimbabweans cannot do in September, Chikowero and Eyre did with their bubbly and riotous books on Zimbabwean music.

Chikowero, the Assistant Professor of African History at the University of California (Buffalo), puts out in “African Music, Power and Being in Colonial Zimbabwe” an endearing homage to indigenous music and ethnomusicological masterstroke.

He rewinds an aural archive spanning over seven decades, from British colonisation to the liberation struggle, to show the mbira’s domain-straddling cultural influence.

Today, the mbira may assure the country a distinctive category in world music but to get there, it had to survive repression by Rhodesian gatekeepers.

In telling the story of Rhodesian’s sustained assault on indigenous ways of being, Chikowero drags missionaries into the dock for doubling up as the colonial state’s incestuous liaisons.

Missionaries are as much part of the narrative as musicians. But Chikowero shreds their collars, taking issue not only with their complicity with but their participation in Rhodesia’s extractive regime. Besides driving out every relic of indigenous culture, including traditional music, missionaries administered taxes, destocking, forced labour and issued edicts for church and state.

Chikowero’s exhaustive scholarship, feverish passion for music, confessional reading of indigenous belief systems and free-spirited verbal facility bring about an at once incisive and involved ethnomusicological project.

The author traverses Harare’s nightlife and unwinds the spool of great Zimbabwean traditions to capture the spiritual and cultural strivings of a longsuffering people. Crucially, music in Chikowero’s book is not just a vastly diverting affair but a programme of social change and, inseparably, the alphabet of the human spirit.

Mbirapocalypse, the conspired demise of the Shona thumb piano, was a bastard policy of Rhodesian incest between church and state.

The State sought to repress Shona spirituality, of which mbira, horn, drum and drum, were connectivity devices, because the First Chimurenga (1896 Shona-Ndebele) had been waged under the charismatic leadership of spirit mediums invoking God against their colonisers.

Its iconoclastic project, designed to sweep away every last cultural residue of the uprising, found willing agents in the mainline Christian denominations whose mission had been also impeded by the indigenous belief system.

Politics and spirituality in music also run the thread of Eyre’s “Lion Songs”. The biography was an easy pick for an ethnomusicology award thanks to its immersion in the subject.

Casting aside the faintest semblance, Eyre shares marijuana and performs with Thomas Mapfumo’s Blacks Unlimited, even borrowing the latter’s Murehwa totem as his stage name, over an endearing friendship of 25 years.

Zimbabwe’s music connoisseur Fred Zindi, veteran journalist Geoff Nyarota, literary notables Chenjerai Hove and Alexander Kanengoni, promoters and Blacks Unlimited guitarists Jonah Sithole, Joshua Dube and other sources reveal the many faces of Mapfumo.

Branching out of an artistic family tree including Marshall Munhumumwe, the jit thoroughbred and Four Brothers frontman; Bernard Chidzero, the novelist and finance minister infamous for ushering in structural adjustment programme; and literary notable Musaemura Zimunya, Mapfumo’s profile in Zimbabwe’s showbiz circuit merited him the title Lion of Zimbabwe.

Mapfumo’s foremost revolution in Zimbabwean music is not only his wartime lyrical confrontation of Rhodesia and post-colonial abuses but, crucially, his resuscitation of the mbira mix. His militant repertoire merits the name Chimurenga music on both scores.

Chikowero and Eyre’s books intersect in the turbulent 1970s when Mapfumo and contemporaries, notably Zimbabwe’s superstar Oliver Mtukudzi and yesteryear icon Zexie Manatsa, locate semiotic resonance for the war effort in repressed canon of the children of tribulation.

But none of the artistes cutting away from the Western covers popular at the time to appropriate the Shona canon for the condition go further than Mapfumo, not least because he is the first to capture the spiritually charged mbira sound into a revolution-themed set.

“Ngoma Yarira”, composed during Mapfumo’s stint with Hallelujah Chicken Run Band, initiates the meeting of mbira and guitar, where the mbira sound is transposed in guitar riffs, facilitating its appearance on the arena of popular culture decades after its suppression by Rhodesian administrators and their clerical instruments.

The Lion of Zimbabwe, then a war-like cub, keeps up with the decolonisation effort “Pfumvu Paruzevha”, “Pamuromo Chete” and “Vana Kuhondo” while Zexie Manatsa was not far behind with “Nyoka Yendara”, “Hangaiwa” and “Tipeiwo Ndege”.

Both rode on metaphors that could lend themselves to ambiguity to evade censorship but the defiance was not lost on the children of tribulation and Mapfumo’s mbira soundtrack is a protest apart.

However, Mapfumo only takes up the mbira itself well into Independence after the umpteenth fallout with legendary guitarist Jonah Sithole who had, for years, commandeered the guitar into a mbira medium. Mapfumo is currently in self-imposed exile in the US. Eyre believes that the Lion of Zimbabwe was “certainly compromised, if not ruined by his move to America”.

It was a bad business decision that may have cut him off the everyday strivings of his people which inspired timeless offerings like “Varombo Kuvarombo”, “Corruption”, “Chipatapata” and “Vanhu Vatema”. Whatever the case, he has been less inspired lately.

Although he is still recording, he is a figure but no longer a force on Zimbabwe’s hit parade. New artistes, including Zimbabwe’s foremost young artiste Jah Prayzah, will sustain his mbira experiment, though none has stepped into his political mantle as yet.

Eyre picks up “Lion Songs” around where Chikowero finishes “African Music, Power and Being in Colonial Zimbabwe” but the magnitude of Chimurenga experiment which is his keynote narrative can only be fully appreciated in light of Chikowero’s book.

Although written apart, the books are mutually code-breaking in the manner doomsday preppers find Daniel and Revelation cross-pollinated. There are few other recent books on Zimbabwean music but “Lion Songs” and “African Music” are a league apart both for rigour and fervour.

“Tuku Backstage” should have been a preferred reference, given Mtukudzi’s stature but can be put down to an extended tabloid, sometimes given to undermining rather than understanding the artiste.

Comments