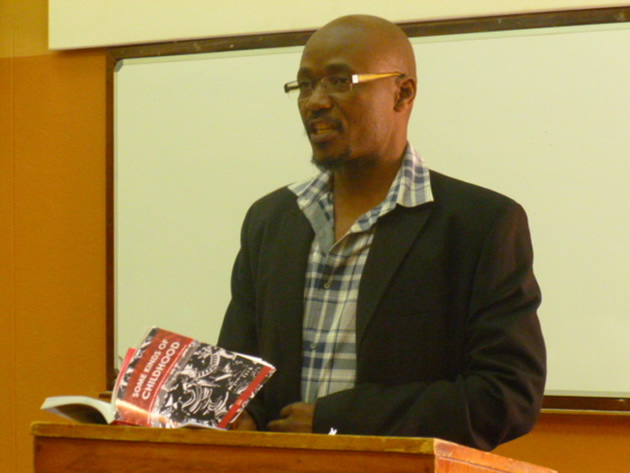

Literary criticism nourishes: Muponde

Beaven Tapureta Bookshelf

Many a time the job of a literary critic has been met with mixed feelings in the world of books but it seems critics are unstoppable, especially when a book is thrown into their territory.

The same question about the role of literary criticism came up at a session held between literary critic and academic Professor Robert Muponde and members of a newly formed creative writing and press club at the University of Zimbabwe.

Professor Muponde had launched his new book “Some Kinds of Childhood: Images of History and Resistance in Zimbabwean Literature” (2015, Africa World Press) the previous evening at the Zimbabwe-Germany Society in Harare. Stories from friends who attended the book launch tell of a well-spent evening with one of Zimbabwe’s academics following in the footsteps of exemplary critics like Professor George Kahari.

The writers club, composed of mainly students from the Department of English and led by Brian Madongonda, could not let Muponde fly back to South Africa where he is based without also giving them a taste of his new book as well as discuss certain issues that trouble them as budding writers. Hence, the overnight decision to ‘‘arrest’’ the Professor!

Never wanting to disappoint the students, Muponde comes panting into the office of his contemporary Memory Chirere in the Department of English at the University of Zimbabwe. It is nearly past lunch hour. There is little time to rest again as Chirere advises him that the venue has changed because the writers club has invited their friends from various departments. He is astonished. He had anticipated a group of less than 15 or 20 students. He immediately abandons the method of presentation he had planned and quickly adopts a new one. Him only knows what he will tell the inquisitive students.

Focus is put on the session. The students swarm into the conference room. The club has not only invited other students from two departments, but their lecturers also, and one of them happened to be Dr Vimbai Chivaura, known for his demand for ‘‘clarity’’ in any matters to do with culture or cultural politics.

On the programme, there is another speaker, Obi Egbuna Jr,. an analyst who runs a column in The Herald. In the audience also sits published writers and poets such as UK-based Spiwe Mahachi, Tinashe Muchuri, Dr Ruby Magosvongwe, Josephine Muganiwa and members of the media. Here is a full-package about to illuminate the room with literary discourse of a certain kind.

Muponde is the first to present. As if he knows the questions already waiting in the heads of young academics, he starts with his background.

For the past 15 years, he has been on what he calls an “intellectual mission”.

“What I have been doing since 2009 or 2000 was to work like a patriot in the sense of establishing what I consider the critical infrastructure necessary for the mind to flourish.”

He pauses. As a lecturer or Professor, he is learned enough to drive home his point.

“As academics, we need to nourish the life of the mind, there’s no part-time thinking. The books that I have so far published are essentially to establish that (critical) infrastructure so that research could be carried out at a higher level to avoid triteness which I see in a number of books and articles written about Zimbabwe.”

Muponde says what he wants to continue to do is also to increase the pleasures of thinking. His interest in childhood, he warns, must not be interpreted as a psychological obsession; it is simply a fascination with the political uses of childhood in literature, in culture, and so forth.

“I was trying to trace our literature’s growth, the contours of its thought, the feeling of its philosophy, and the touch of its imagination,” says Muponde.

“Some Kinds of Childhood” is a book the author describes as a critical biography of the literature itself from 1972 to 2013. It is divided into five parts with topics “Spaces of Memory”, “Children of Resistance”, “Girlhoods”, “Dystopic Childhoods” and “The Postnational as Postchildhood”.

In this book, Muponde discusses childhood as portrayed in about 10 selected Zimbabwean books which include NoViolet Bulawayo’s “We Need New Names”, Christopher Mlalazi’s “Running with Mother”, Memory Chirere’s “Somewhere In This Country”, and Tsitsi Dangarembga’s “Nervous Conditions”.

Muponde chooses to read two extracts from his book to demonstrate how one can bring a number of disciplines to the understanding of a certain text which may be a single sentence or paragraph in a work of poetry or fiction.

The first extract he reads is from the essay critiquing Tsitsi Dangarembga’s “Nervous Conditions”. The essay is titled “Girlhood as a Gift from Death”.

Later he reads a second extract from an essay “Postnational childhood-Postcolonial Postchildhood?” which explores childhood in the book “We Need New Names”.

It was interesting for students to note how Muponde looked at the first sentence in “Nervous Conditions” from a number of angles to understand the narrator/main character, Tambu. “I was not sorry when my brother died,” begins the award-winning novel “Nervous Conditions”.

According to Muponde, just by examining that sentence helps to open new pathways for critical debate. This critical look, this examining, is lacking in literary studies, he says.

“What I think is lacking in literary studies is the engagement with textuality itself, we tend to just comment on ideology, we avoid engaging with the word,” explains Muponde.

The extract indeed demonstrated a multiplicity of perspectives from which he looked at Dangarembga’s novel. Muponde actually says in his analysis of the novel’s first sentence, he brings in jurisprudence, philosophy of war, death studies, other post-disciplinary perspectives and literary philosophies.

His next extract then adds to the intellectual load he has already put on the students. He dwells on “We Need New Names” and also touches Dambudzo Marechera’s “House of Hunger” and “Bones” by Chenjerai Hove while analysing how these books make use of the ‘‘toilet’’ motif.

Muponde says that with these selected texts he tries to see the ways in which Zimbabwean writers have dealt with the issue of ‘open defecation’ as a trope or literary metaphor that helps to understand the condition of a society.

The two extracts were enough for the audience to see for themselves the joyful labour and yet complex faith, which literary critics have to go through. But likening the pain of giving birth to a country to the pain of relieving oneself after eating guavas (a scene in “We Need New Names”) really makes a few hands shoot up at the Professor during open discussion.

“Why is it that writers who write begging about Zimbabwe are the ones who get awards?” asks Dr Vimbai Chivaura. And then comes the declaration from Newten Maidza, a lecturer, about the first sentence analysis: “Critics confuse the people. Why do critics mystify straightforward things? I don’t think that helps communication.” A student Elizabeth Dakwa, adds, “How does criticising other people’s works help us to be practical. We are living in a world that now demands practice than theory.”

It comes back to the role of the critic. What values do critics propagate? In his answers, Muponde says more investment should be made in critical awareness because for any society to develop it requires criticism.

“In literature, criticism does not mean fault-finding, rather it is the deepening of insight so that we develop a higher level of understanding. Criticism is progressive,” says Muponde.

Do critics mystify? Muponde says, “They clarify, they don’t mystify. In any case language is semantically, symbolically loaded. It’s never a transparent kind of communication. It still needs an interpreter. Even in church, you need someone to interpret a certain Bible verse so that more meanings are generated.”

The second speaker, Obi Egbuna Jr is an aggressive orator. He spoke about the need for strategic investment in the information industry and therefore the creation of a UZ creative writing and press club is worthwhile. Egbuna Jr gave a profound analysis of the links that exist between African history and African-American history.

It was an afternoon of debate which never was resolved as some questions were left hanging due to the limitation of time. Dr Chivaura and others would have been happy to debate the decolonisation and imperialistic camps that seem to differentiate literature, especially African literature.

At events such as this, spoken word is a spice that eases tempers and Rufaro Chinyangu and his colleague Munyaradzi performed their narrative poetry with Munyaradzi playing mbira in the background. If given a chance, Chinyangu says he aims to take spoken word to another level in Zimbabwe through his group known as Tungenyika.

Robert Muponde is Associate Professor of English in the School of Languages, Literature and Media at the University of Witwatersrand in South Africa. He has widely published his literary criticism in books such as “Sign and Taboo: Perspectives on the Poetic Fiction of Yvonne Vera”, “Versions of Zimbabwe: New Approaches to Literature and Culture”, and “Manning the Nation: Father Figures in Zimbabwean Literature and Society”. Muponde also features in “No More Plastic Balls: New Voices in Zimbabwean Short Story” which was published in 2000 by College Press.

Comments