Lessons from Ugandan oil experience

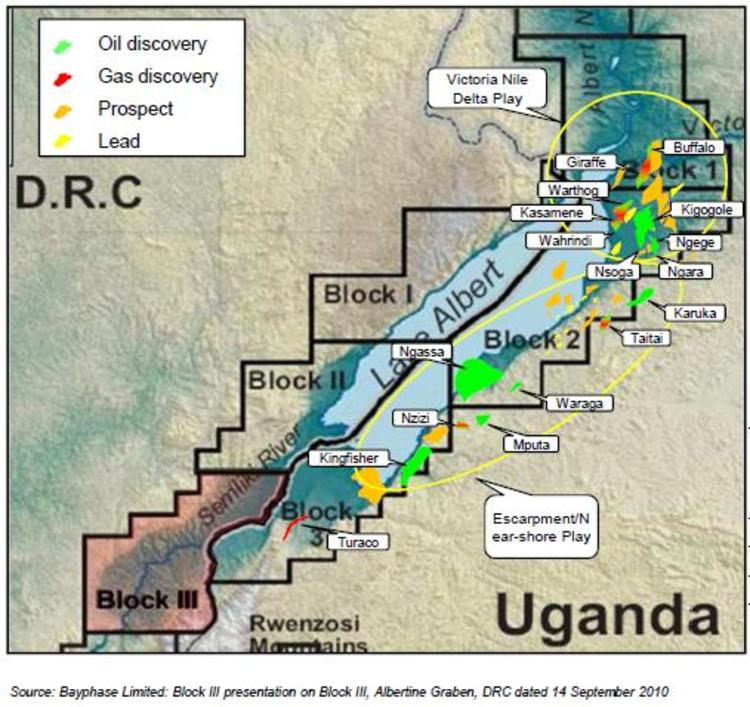

The Albertine Graben region stretches from the border with Sudan in the North to Lake Edward in the South covering an area of 24 000 square kilometres and extending into the DRC

E Doro and U Kufakurinani

Often it is critical to begin things right from the outset to prepare for a better eventuality rather than start something on a wrong footing. African governments are ill-equipped to deal with discoveries of precious resources and they begin with so much try and errors that only serve to compromise efficient and effective exploitation of resources that could otherwise be deployed to address pressing developmental needs.

The manner in which resources are governed and the institutions put in place often lead to a somewhat disappointing outcome. The importance of institutions in the effective and efficient co-option natural resources can never be overemphasised. The quality of institutions can determine whether a resource is a curse or a blessing and abundant resources in an economy can be lucratively exploited if institutions are functional.

Parliaments, for example, are critical institutions in the governance of resources. They can contribute to the enactment of laws which regulate the extractive industry and the engagement with stakeholders in the creation of an arena of national dialogue and involvement in policy making within the natural resource sector. Democratic governance requires parliament to serve three purposes, representing citizens, making or shaping laws and policies and overseeing the executive.

In the management of natural resources, legislators bear responsibility for ensuring that policy and regulatory frameworks support sustainable use and exploitation and that government appropriately allocate and account for revenue.

Ugandan experience with their discovery of oil is quite illuminating. Oil exploration was first done in the Albertine Graben in the 1920s. In 2006 the Ugandan government confirmed the existence of commercially viable deposits. The Albertine Graben region stretches from the border with Sudan in the North to Lake Edward in the South covering an area of 24 000 square kilometres and extending into the DRC. In 2006, the government of Uganda confirmed the existence of commercially viable oil deposits with estimated reserves worth about 2,5 billion barrels.

The country has the potential to become a middle oil producer like such countries as Chad, DRC and Gabon. The current national oil reserves are estimated to have the potential to generate $2 billion in annual revenue for more than 20 years. A World Bank Report estimates that Uganda’s oil has the potential to double revenue between 6-10 years and to constitute 10-15 percent of Gross Domestic Product. Uganda’s oil is however difficult to access and it will require large investments amounting to 10 billion dollars for optimal developments of the oil fields to be realised.

Full scale production was tabled for 2016 as the country grappled with the upstream aspects of oil production which includes licensing, exploration and transportation.

Weak governance institutions including the parliament have, however, allowed for the emergence of an opaque terrain where gross corrupt deals and under hand transactions are processed. The result of such has been to negatively impact the effective co-option of the resources into the national development agenda.

Admittedly, the Ugandan parliament has frantically tried to niche out space for national dialogue on the governance and control of the natural resources by advocating transparent mechanisms in compensation of local communities displaced by exploitation of the resources, granting of licenses, extraction and revenue receipts. However, these efforts have met with serious challenges emanating partly from the limited power that it holds.

More often than not, the presence of resources in Africa has sparked greed and the construction of African politics along prebendalism, patronage, crony-ism and what Bayart(1993) terms “politics of the belly”. It is within this context that we must appreciate the challenges that the Ugandan parliament has faced in effort to meaningfully benefit from oil resources.

The absence of a comprehensive legal framework to deal with oil exploration led to the promulgation of a National Oil and Gas Policy in 2008 by the government as an ad hoc governance framework pending the enactment of comprehensive legislation.

The 2008 Oil and Gas Policy espouses as some of its objectives the efficient and effective management of Uganda’s oil and gas resources; encouragement of transparency in the management of the industry; and ensuring that revenues from the oil and gas sectors are properly managed and utilised to create wealth.

Amongst its principles, the policy highlights efficient resource management; and the need to insulate the economy from shocks of oil prices by creating a Ugandan Petroleum Fund.

It emphasises other key issues like transparency and sustainability, conflict resolution and meeting the needs and demands of the local communities.

It also envisages specific roles for various government departments involved in oil and gas, such as the Ministry of Energy, the National Oil Company and the National Petroleum Authority. Section 7.2.1 of the policy provides that Parliament should be in charge of monitoring performance in the petroleum sector through policy statements, annual budgets review and the creation of an oversight committee on the oil and gas sector.

However, the National Oil and Gas Policy did not provide an adequate framework for effective governance. It left undefined several key fundamental governance issues relating to effective oversight, such as ensuring that a cogent legislative framework to regulate oil exploration and production was in place.

Meanwhile, despite the apparent absence of the laws to regulate the oil and gas sectors, government had already actively begun handing out contracts to oil companies without the approval or ratification of parliament. The situation promoted the emergence of an opaque oil-governance terrain, which could be manipulated by corrupt state officials for personal gain.

This dynamic, of primitive accumulation by state officials in an environment of systematic opacity and governance disruption, is a key feature in most oil rich African countries.

Corruption and bad governance construct a pervasive political economy of appropriation, which facilitates leakages and deprives the state of resources which could otherwise be allocated to productive human development and poverty alleviation.

In an attempt to control the industry and the public capture of revenue, Parliament in Uganda initially used the common means of passing motions, initiating questions, conducting public hearing and summoning ministers before Committees; but without much success.

The absence of a comprehensive legal framework within the oil sector compelled Parliament to challenge government in a more ‘forceful’ way over how oil exploration was being undertaken.

In October 2011, parliament moved a resolution to convene a special session which implored government to submit all the necessary bills for the development of the oil sector for consideration within 30 days from the date of resolution.

Parliament also declared a moratorium on the granting of new oil exploration licences in October 2011, until specific conditions had been fulfilled by the government including: the passage of all the necessary laws; the review of all the Production Sharing Agreements (PSAs) by government; accountability of revenue so far received from the sector covering license fees, signature bonuses, taxes and royalties; and the removal and desisting from executing contracts within the oil industries with confidentiality clauses. However, perhaps predictably, this moratorium was ignored by the executive, which went on to award two oil producing agreements with an Anglo-Irish firm Tullow Oil on February 3, 2012.

The 30 days to bring laws governing the petroleum sector, granted to the executive by parliament, expired without any bills being tabled before the house. However, on February 8 and 15, 2013, the government tabled two petroleum bills before parliament, the Petroleum Expropriation, Development and Production Bill; and the Petroleum Gas Processing and Conversion, Transportation and Storage Bill. Both were intended to give effect to Article 244 of the constitution. The former was to regulate petroleum refining; gas processing and conversion; transportation and storage of petroleum; promoting policy formulation; and coordination and management of petroleum refining, gas processing and conversion.

The latter was to regulate petroleum exploration, development and production; to establish the Petroleum Authority of Uganda, to provide for the National Oil Company; and to regulate the licensing, amongst other things.

The Petroleum Expropriation, Development and Production Bill stirred a lot of controversy and debate in the house with regards to certain provisions within it. Specifically, Clause 6 was viewed as giving a monopoly of powers over the allocation, approval and revocation of exploration licenses to the Minister of Energy and Mineral Development.

Opposition MPs and some from the ruling party virulently opposed the passage of the Bill and called for the repeal of Clause 6. Civil society organisations also protested that there should be established a Public Interest Accountability Committee to provide executive oversight, as was the case in Ghana.

The dominant party in government, the National Resistance Movement (NRM), was eventually able to use its majority in parliament to force the bill through on December 7, 2012, without taking on board the proposed amendments.

The controversial Bill established the Petroleum Authority of Uganda to monitor and regulate exploration, production process, transporting and storage of petroleum in the country.

A global Witness Report of 2010 states that although the bill provides for the independence of the Authority, it also empowers the minister to give policy directives to the Authority and requires compliance with those directives.

The Report further criticises the bill for making the appointment of key figures in the petroleum industry fall outside the purview of Parliament. The Minister of Petroleum was a presidential appointee and who had the absolute powers to appoint key positions in the National Petroleum Authority outside Parliamentary oversight.

As the report notes, “this creates the risk that the oversight function of parliament over the Petroleum Authority is negated and positions could be given on the basis of personal connections and loyalties rather than merit.” Clause 6 had the potential to allow the minister to initiate deals behind closed doors with no public scrutiny which at worst was likely to promote corruption; and at best certainly did nothing to limit it.

Despite robust engagements by parliament, the frenetic efforts of the legislature in bringing reforms into key natural resource governance has achieved very little.

The legislative environment is highly constrained and skewed much in favour of the powerful political elites who most often have a stake in the perpetuation of an unsanitary and opaque terrain where they can loot and fund their own agenda.

The abilities of parliament is thus curtailed by the limits imposed upon it by its constitutional mandate which relegates them into playing mere watch dog roles and raising issues on what they perceive as violations of the principles of good governance without playing an active part in redressing or enforcement of recommendations.

If a resource curse is to emerge in this scenario, is will be largely a reflection of a governance deficit than a resource abundance crisis.

Countries such as US, Botswana and Norway, which have developed and evolved efficient systems of checks and balances, have managed to mitigate the resource curse dilemma. (Based on a research done by E Doro and U Kufakurinani, “Dilemmas and Uncertainties in Resource Governance”, forthcoming)

- E Doro is a researcher in the Parliament of Zimbabwe and a PhD candidate with Stellenbosch University, South Africa.

- Ushehwedu Kufakurinani is an Economic Historian by training based at the University of Zimbabwe. He is the current national coordinator for Economic Thinkers (ET) — ZimChapter, a local group affiliated to Rethinking Economics ([email protected])

Comments