Is scrapping Shakespeare a sound option?

Literature Today With Stanely Mushava

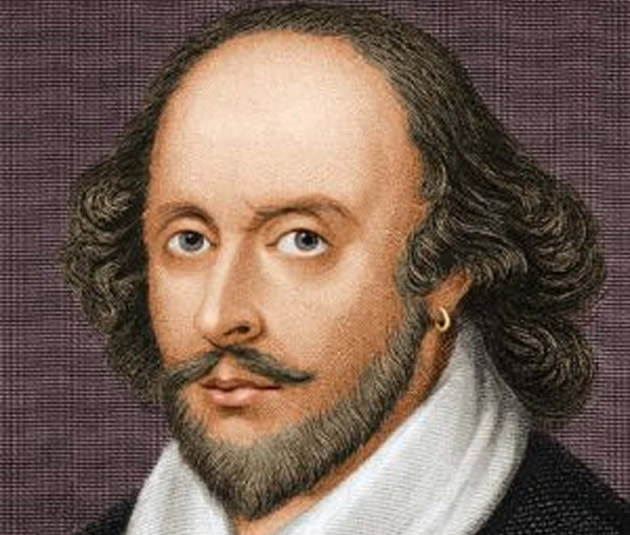

William Shakespeare is not new to posthumous conspiracy. Latter-day men of letters such as G.B Shaw and Leo Tolstoy have questioned the universal acclamation with which Shakespeare is read.

For them, the world is too generous in its estimation of the man whose work Swinburne calls “the crowning glory of genius, the final miracle and transcendent gift of poetry.”

Tolstoy, whose scruples are rich ground for controversy, claims to have found in Shakespeare no delight, but revulsion and boredom.

The same work Tolstoy acknowledges to be universally subscribed as “the summit of perfection,” he dismisses as “trivial and positively bad.”

Other sacrileges against Shakespeare’s estate include charges levelled to question the authorship of his masterpieces and to impugn his personality.

More contemporary objections to Shakespeare rest on his alleged irrelevance to or incompatibility with certain classes and cultures.

The most recent of such is the appeal to our parliamentarians by Zimbabwe’s former ambassador to Mozambique, ex-combatant and writer, Retired Brigadier-General Agrippa Mutambara, to scrap Shakespeare out of our school curriculum and make way for liberation war chronicles.

“This history is a record of the past and must be passed through generations, and through you MPs I am making a plea that let us flush out Shakespeare from the school curriculum now and not later,” Ambassador Mutambara was quoted by a local daily.

Speaking at the launch of his autobiography, “The Rebel in Me,” at Parliament building last week, Ambassador Mutambara also called for the scrapping of Chinua Achebe, ostensibly for his lack of immediacy to the Zimbabwean cause.

“We have literature of our glorious struggle, but we have had writers like Chinua Achebe’s fictional literature studied in our schools,” Ambassador Mutambara said.

“However, we can do better than that by embracing our literature which is of real-life experiences and true history.

“If use of language is what attracts us to Shakespeare and Achebe, then we should use that rich language to write our true life experiences. Chinua Achebe is a very good writer, but of what value is it to our culture and systems?” Ambassador Mutambara said.

Ambassador Mutambara’s appeal is, in my opinion, a wrong prescription for the accurate diagnosis.

For a summative response, I will argue that we must flush out Shakespeare from our school curriculum neither now nor later but never.

First though, I will acknowledge the setting for the appeal.

To his credit, Mutambara is alive to the very present danger of lapsing out of touch with chronicles of our own experiences as a people.

Quite clearly, there is a void in our culture industry — one that negates claims of identity and responsibility.

There is the real danger of ceding significant strands of our history to oblivion.

But this we should fault on our leaders and icons’ reluctance to document their experiences instead of the exposure to creative best practice within other cultures. Biography is a rich site for engagement with history.

While memoirs are often prone to issues of authenticity, having a varied canon of them is desirable as it allows us to corroborate or fault one narrative against another towards a fuller understanding of our history.

It is the case Ambassador Mutambara is bent to champion.

His graveside eulogy for Major-General Elijah Bandama at the National Shrine last year featured an impassioned appeal to that effect.

“Most importantly, I think our leadership should realise, but if that history does not filter into our school system, people will not get to hear about it,” Ambassador Mutambara added.

“Government should recognise our efforts and ensure that this literature we write gets into our schools than reading about Shakespeare which has got no relevance to our culture,” he said.

I agree with Ambassador Mutambara to the extent that he faults the gaping deficit that we have of our own stories.

We have also been making humble endeavours in these columns to urge the nation to touch base and reconnect with itself as the only credible basis for claiming the future.

One such submission, “SOS for literature in indigenous languages,” penned around this time last year was taken by local anthropologist Taazara Munhumutema to Zimbabwe Heritage Trust whom he said promised to buy rights to some of the indigenous titles from publishers.

The problem is really not being occupied by offshore cultural products but failing to preserve and value our own.

We have often pointed with indignation to the irony that while the Greeks, the Romans and the English have fortified their successive poetic ages against the wear of centuries, Zimbabweans cannot account for its own defining creations.

Brilliant first generation novelists and historians like Stanelake Samkange are ignored and out of circulation. No one seems to care.

Our arena, which used to host prolific writers, has been vastly downgraded but for a few resilient exceptions who write not so much for commercial incentives but for the love of culture.

Is it not a debilitating symptom that an American newcomer like Veronica Roth makes US$50 million from her three books between 2011 and 2014 while a Zimbabwean thoroughbred like Aaron Chiundura Moyo makes US$400 from his 14 books between 2000 and 2014?

Somebody may raise the issue of language. But no one should promote our languages on our behalf.

We should do so by supporting our creative industry. The Nigerians are a sterling example.

As Moyo said, it is telling enough that we now have words like “igwe” in our daily lexicon whereas Yoruba do not have words like “hwereshenga” in theirs.

Ambassador Mutambara is right in this regard.

However, there are serious problems with his prescription.

When it comes to legislating literature, however, I stand on the clear and unequivocal view that Parliament has no business deciding what we can read or what we cannot read.

Literature, being an open domain for ideas, needs to run autonomously without puritanical, protectionist or parochial interference.

If we do not like other people’s books we should write our own, as Achebe said, instead of gagging them.

“Things for Apart” is juxtaposed with incomparable credit to “Heart of Darkness.” There will never arise a need to ban Conrad’s crass title as long as there is Achebe’s response.

That is because the study of books must never be meant to nurture ideological automatons but free, conscious, critical thinkers capable of conscious engagement with texts from any world-view.

To circumscribe literature to the eulogisation of the struggle is to make liberation a stand-alone and self-sufficient end.

That, for me, erroneously presupposes that millions like us were born after the end of history.

Writings from other cultures, notably Ghana and China, served as an ideological engine for the liberation struggle.

Liberation fighters were exposed to a range of ideas but consciously inclined themselves towards what could be appropriated for the affirmation of the native.

For a practical demonstration, Shakespearean literature in the current curriculum is not mutually exclusive with our own narratives.

“Antony and Cleopatra,” though lacking in other elements of proximity, is by no means insignificant in its handling of universal phenomena like love and loyalty.

When we studied it in high school five years ago, it was along with “And Now the Poets Speak,” an anthology of poetry inspired by Zimbabwe’s liberation struggle.

Shakespeare’s occupation with Roman opulence and Egyptian decadence did not detach us from the Povo-oriented poems of Carlos Chombo, Charles Mungoshi and Chenjerai Hove.

It was also concurrent with Mozambican writer Louis Benardo-Honwana’s “We Killed Mangy-Dog,” no mean feat as far as indictment of colonialism are concerned.

Nigerian novelist Chimamanda Ngozi-Adichie’s “Purple Hibiscus,” took a different, all the same significant, strand, with respect to the pursuit for freedom.

It would be superfluous for us to defend the relevance of Chinua Achebe.

The inaugural installment for this space, “Achebe and the African Rennaisance” demonstrates how this Igbo cockerel, whose crowing awakened Africa, cannot be gainsaid.

To buttress the foregoing, for titles to his first two novels, Achebe references Yeats’s “The Second Coming” and Eliot’s “The Journey of the Magi.”

Foreign allusion can be hardly said to compromise Achebe’s Afro-centric beat.

Rather, it demonstrates that Africa is not a cultural island. Zimbabwe should not strive to be one.

Stanely Mushava blogs at medleycity.wordpress.com

Comments