‘HIV is manageable in Zim’

Samantha Nyamayedenga

When I came to the UK in September 2015 to study at the University of Sussex, I was told that the HIV medication I was on, was not available, which was frustrating.

It was frustrating because instead of taking a single pill containing different antiretroviral drugs, as I had been doing at home in Zimbabwe, I now had to take three different pills a day.

I’m in the UK studying for a Masters in Development Studies and recently we had a class discussing on what role health plays in the interaction with citizenship. The main subject was HIV, and it was interesting to see the different assumptions people make because of the difference in prevalence in HIV between countries such as the UK and Zimbabwe.

Access to antiretroviral medication

In the UK in 2014, the adult rate of HIV prevalence was 0,19 percent (AVERT) compared to 16,7 percent in Zimbabwe (UNAIDS). Furthermore, in the UK 91 percent of HIV positive adults are on treatment compared to 63,4 percent in Zimbabwe (UNAIDS).

It is well known that poverty is a driver of HIV, and of course the UK and Zimbabwe have very different economic situations which can help explain the difference in HIV statistics. Everyone in the UK, should they need it, has access to antiretrovirals which is very unlike the situation in some parts of Zimbabwe.

In the UK in 2014, only 29 children were newly diagnosed with HIV and only three children were known to have acquired HIV from their mothers (AVERT). In Zimbabwe 6,6 percent of new HIV cases were from mother-to-child transmission (UNAIDS). However, it is fair to point out the rate of babies born with HIV in 2009 was 29 percent, so progress is being made.

Failings to deal with HIV

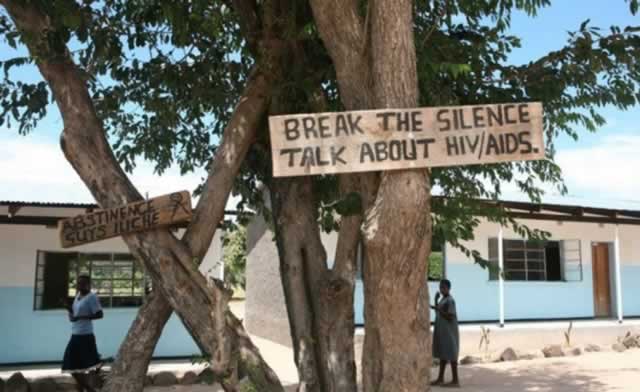

Despite the difference in access to medication between the two countries, I have observed that both Zimbabwe and the UK share the same failures in dealing with HIV. For example, there are barriers to HIV prevention in both countries due to stigma and discrimination and lack of HIV knowledge.

HIV is still associated with certain groups of people in the UK, who consider it “the disease of the gay”. In Zimbabwe, it is considered by some as “the disease caused by promiscuity”. Therefore many people living with HIV in Zimbabwe are not keen on disclosing their status for fear of being judged.

Even though HIV seems to be under control in both countries there is still a number of people who are not aware of their HIV diagnosis. In the UK 17 percent of people living with HIV are undiagnosed and in Zimbabwe only 30 percent of young people are aware of their status. The major drivers of these situations are the lack of knowledge and stigma.

Managing HIV

In our class discussion, many people said that HIV was only manageable in the UK and nowhere else, especially Africa. Even the person who led the lecture agreed with the rest of the students. I wanted to raise my hand and tell them that I disagreed.

I wanted to tell them that I am a person living with HIV from Zimbabwe who is doing well because actually HIV is manageable in Zimbabwe. I wanted to say that my immune system is very strong thanks to the structures in place there. I did not speak up because I was afraid of generalising Zimbabwe’s situation regarding HIV. The only proof that I could provide in arguing against my fellow students was my own personal experience which I was unprepared to share.

Had I been prepared enough in sharing my story it would have gone like this: My main concern is that taking antiretroviral drugs for the rest of your life can sometimes result in treatment fatigue. What happens if the quantity of drugs you need to take increases? Is this not demoralising? I have no problem with the combination of antiretrovirals that I am currently receiving in the UK. However, when I was told I needed to take combination therapy in three drugs instead of just a single I felt disheartened. From this personal experience I learnt that we should exercise caution and try to avoid generalising HIV as only manageable in the UK. —

- Samantha Nyamayedenga is a member of Key Correspondents, a citizen journalism network reporting for action on HIV (visit at www.KeyCorrespondents.org). The network is supported by the International HIV/AIDS Alliance.

Comments