History in democracy promotion

on the Twentieth Century.”

To many human rights activists the greatest threat to democracy is authoritarianism and totalitarianism — that unwanted rule of tyranny and dictatorships. In explaining the titanic clash between tyranny and democracy there is always excessive use of memory and history, as the much-publicised notoriety of Adolf Hitler and his Nazis is often used to illustrate how terrible the clash between democracy and totalitarianism can be.

Memory and history are of course relative and can be manipulated and applied differently for various goals and intents. The memory of defeated Rhodesian colonialists is not necessarily the same as that of the freedom fighters that brought Rhodesian colonial rule to a crashing end. To the typical conservative Rhodesian the end of colonial rule in Zimbabwe is a memory of lost opportunities, a reminder of black barbarism messing up with progressive white civilisation, a racial myth to all others, and an axiom to the proponents.

Of course the liberator’s memory is that of bringing about a joyous end to an era of humiliating domination of the African by the colonial supremacist European — a heroic feat of crumbling the egregious colonial empires.

Humanity has learned a lot from its errors in history, moderating supremacy with tolerance, conquest with internationalism, slavery with humanity, and hopefully war with peace, barring the excesses of imperialism. Humanity must come to a point where defending one’s interests does not equal neglecting or thwarting the interests of others — the way perpetrators of imperialism carry out their ruinous ideology, especially through the sabre-rattling and war-mongering foreign policy of Western powers.

For the revolutionary African prominent humanists are those founding fathers of independence for the African continent, the likes of the legendary Kwame Nkrumah, the prolific nationalist Amilcar Cabral, the revolutionary Abdel Nasser, the passionate Samora Moises Machel, the heroic Thomas Sankara, the highly principled Robert Mugabe, the fatherly Julius Nyerere, the charismatic Patrice Lumumba and the respected Nelson Mandela, among many other icons.

For the Americans the mass-killing George Washington is a high-level humanist who is unreservedly honoured for founding “freedom and happiness” for the United

States, just like Captain James Cook is held in high esteem for his role in leading a murderous gang of convicted criminals in annihilating the Aboriginal people of Australia. The Caucasian Australians commemorate 26 January as the “Australia Day,” the day Cook first set foot in Australia. The Aboriginal people hold parallel commemorations on the same day known in their circles as the “Invasion Day,” clearly a more appropriate way of remembering this fateful day.

This year the two groups had a clash after opposition leader Tony Abbott reportedly implied that the Aboriginal Tent Embassy next to the Australian Federal Parliament be pulled down, and that it was about time the Aboriginal people “moved on.” Infuriated Aboriginal protestors could take none of Abbott’s alleged utterances and Prime Minister Julia Gillard lost a shoe as she escaped from the advancing protestors, alongside a fleeing Abbott.

For Todorov a humanist is a philosopher and practitioner of democracy, and as such a pragmatist. Humanism is neither hedonistic nor fanatical, but rather an attitude premised on the principle that all people have the same rights, and the same claim to respect, regardless of the fact they may not live exactly the same way as each other.

True humanists do not fool themselves in the belief that democracy in and of itself will yield final answers to humanity’s problems or bring heaven on earth. By giving people the inalienable right to choose, democracy inevitably makes the evil in man and in the world a thing of substance within human life, directly arising from that very freedom to choose; indeed with many opting to choose not only the good but also the evil.

In this context it is impossible for democracy in and of itself to bring paradise on earth, to be all good and glorious, precisely because the choice of evil sometimes prevails as much as that of good.

Democracy often assumes that human sociability and incompleteness can be modified to lead people to cherish each other, to respect each other, and even to love one another. This of course is a baseless denial of the reality that humanity often allows people to treat one another merely as a means to selfish ends.

Capitalism by its very nature presents a perpetuating risk that people will always prey on each other, the way the West preys on Arab nations in order to plunder their oil, or the way the same Westerners prey on African people in order to plunder their mineral-rich continent, like Nato recently preyed on Libyans to allow France, the US and Britain unfettered access to Libyan oil.

Humanism offers to the world the possibility that people will see and “treat others as individuals, not as objects or mere label-bearers of one kind or another; and in that belief lies the best hope for mankind,” so writes author AC Grayling.

A pragmatic and down-to-earth democracy does not vacuously sing liberties and freedoms without qualification or limitations. Rather it recognises its failings and its capacity for evil, much as it acknowledges the humanistic impulses towards the flourishing of humanity.

Memory and history have a pivotal role in shaping the course of humanism or democracy, and history makers often mislead us into thinking that our choices are between remembering and forgetting the horrors of humanity, or the glories of it. Indeed there is always a choice to remember events in our lives. But there is no such thing as a choice to forget; and this is simply because forgetting is not something one can do by an act of will.

We can never forget slavery or colonialism, much as we may want to remember the virtues of democracy and modern-day internationalism, or even to do the in-thing called moving on, something historical wrong-doers are very quick to urge their victims to do, like Abbott wants the Aboriginals to do in relation to the atrocities visited upon them by the white man.

When we remember our past the sense of remembering is quite relative, and we have choices to remember things in different ways. For some people the only way to face the future is to trivialise the past. This is why ex-colonisers are quite keen to urge the formerly colonised “not to live in the past,” and to forget about the terrible era of slavery and colonial brutalities. Writing the historical evil of Westerners is usually derided as lack of appreciation for progressive thinking, and this writer is often reminded about the backwardness of highlighting humanity’s errors of the past, especially by those who claim today to be captains of civilisation.

For the vanguard of the liberation of Africa the past is often remembered in sacred and heroic ways — always highlighting the victories of pre-independence nationalism, as well as overplaying victimhood by the colonial brutes, and those who are viewed as failing to place appropriate reverence for the heroics of those who took part in the struggle for independence are vilified as traitors.

These various ways of remembering the past do have an impact on humanism and democracy. The West wants to promote in former colonies a democracy that will uphold Western global leadership on the one hand, and deride independent nationalism by former colonies on the other. This is precisely why Zimbabwe’s compulsory reclamation of colonially white-held agrarian land does not fit in the Western lexicon of democracy.

By virtue of the unanimity of Zimbabweans over the principle of compulsory reclamation of this land, the land reform programme must be a democratic development by every definition. However, this kind of democracy does not make it easy for ex-colonisers to face the future, and as such it is derided as grossly undemocratic, if not outright barbaric. Robert Mugabe has been rated the Devil in Chief for propounding uncivilised governance ever since his Government decided to give back Zimbabwean land to its rightful indigenous owners.

As outlined by Todorov, democracy today faces three main dangers. Firstly, there is too much identity politics and this has created a narrow-minded approach to secularism where democracy has been reduced to the replicating of Western societies across the world — a phenomenon that has immensely contributed to global instability.

Secondly, the adherence to moral correctness sometimes gets too slavish; resulting in the subjugation of certain groups of people by others wielding the power and might to define the way for all others.

Lastly Todorov talks of “over-instrumentalisation,” where the concern is on over-reliance upon the means to achieve democratic ends than about the end itself. This has resulted in prescriptive democracy defined by specific Western formulae almost to the point of telling all other lesser people how to breathe and live their lives.

While individual liberty is a fundamental basis for democracy, it must be noted that equally fundamental to democracy is a sense of belonging to a moral community. Mankind is not going to know happiness simply on the basis that every single human being has absolute individual liberty. In fact that could easily cause anarchy.

Individual liberties without due consideration of community values will hide from us the deadly cost of individual freedom. From a Christian point of view, such limitless individual liberty will separate the individual first from God, second from his fellow man, and third from himself or herself.

As individual liberties increase, man becomes more and more materialistic, resulting in God becoming irrelevant as the belief in the supremacy of man overshadows the relevance of any superior being. This is precisely why the campaign for gay marriages and legalisation of homosexuality does not usually accommodate moral arguments, only emphasising on individual liberties, reducing matters of morality to prejudice and egregious bias.

Individual liberties when in excess will always trivialise fellowship as other people around become increasingly irrelevant, with each individual’s circle of concern shrinking from community to family, and from family to the selfish self.

Unfortunately and sadly the self will always vanish too. An individual separated from the support of the community and family becomes nothing but a collection of incoherent impulses, an alienated and inauthentic being that is vulnerable to mental disorders and social pressures as seen most in Western democracies. These ills manifest through disorders like schizophrenia, depression, suicides, serial killing, sex-changing and many other signs of social sickness and alienation of the self.

The argument here is that democracy must not purchase the freedom of the individual at the cost of forfeiting common societal values or social relations, nor by sacrificing the integrity of moral uprightness. Individual liberty acquired at the expense of society’s common values is dangerously deceptive and will lead to the individual losing their own self.

This is precisely why those arguing for the legalisation of homosexuality in Zimbabwe on the premise of individual liberties must realise that the Zimbabwean society is not about to pay for individual liberties the cost of forfeiting its core common values, or to purchase the favour for international aid by sacrificing commonly held community values. Malawians under Lady Banda have become a donor-fearing country more than they are a God-fearing people, choosing to pay for aid by casting away the fear for God. May the thought forever perish in regard to Zimbabwe!

A democracy that attacks the coherence of a community to create an assortment of freelancing individuals is a betrayal to the true essence of the principle of rule of the people, by the people and for the people — that Aristotelian concept of democracy.

Africa we are one and together we will overcome. It is homeland or death!

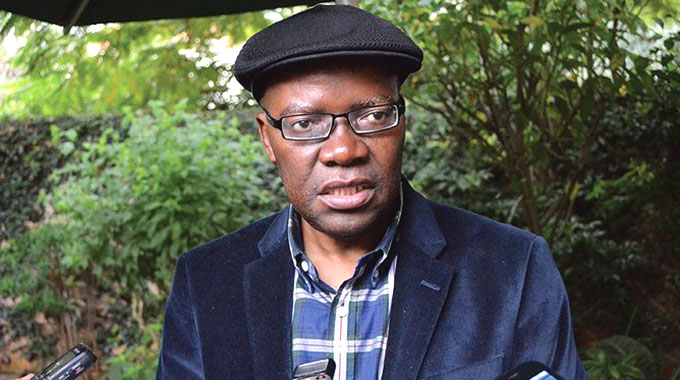

Reason Wafawarova is a political writer based in Sydney, Australia.

Comments