Heroism, leadership failure

Reason Wafawarova on Thursday

The tradition that created Mandela, and to a lesser extent Desmond Tutu, defines the culture the West is too keen to have Africans adopt. The tradition is good for Western businesses, and excellent for trade. Needless to say, this tradition is unhelpful to the African cause.

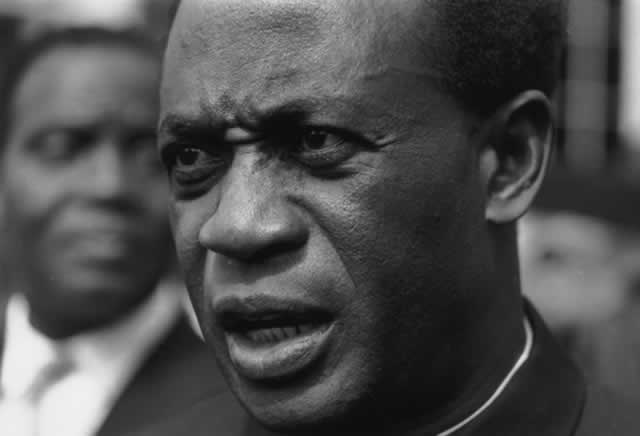

Often post-independence imperialist meddling has been blamed for the downfall or demise of our post-colonial liberation heroes, like Patrice Lumumba, Samora Machel and Kwame Nkrumah.

Now that we in Zimbabwe have as usual celebrated Heroes Day this month, it is important for us to introspectively look at how much justice we have done in return for the sacrifices of those who paid the supreme price for our freedom.

Much as Kwame Nkrumah was pushed out with the help of the obvious hand of imperialistic powers, particularly Britain and the United States, it can neither be dismissed nor disputed that at the material time Ghanaians were bewildered, if not disappointed by the outcome of self-rule, perhaps the same way Zimbabweans that identify with Western-funded political parties are today.

At the height of the fall of colonial empires, our people were hyped into the euphoric hope that with liberation would come the opportunity for the African to prove his worth, and for us in Zimbabwe, the incessant shedding of blood towards the goal of independence only meant the expectation was even higher.

The question that needs a speedy answer is why the post-independence African has found little around him to instill the confidence that we as Africans can manage the affairs of our own countries.

Instead of forging effective advancement policies designed to make the continent a global economic competitor, our leadership has largely instilled in our people the importance of African dependency, that is when our leaders are not fluently explaining away leadership failure by highlighting the evils of the colonial legacy, or in Zimbabwe’s case blaming the illegal sanctions regime imposed by the West back in 2001.

I am an international relations scholar and practitioner, and I will be the first one to point out the ruinous effect of external factors on Africa today, including the indisputable role of such factors to the woes of our people today.

But it makes up pathetic apologetics for anyone to overlook the internal factors that have stalled or derailed development in post-colonial Africa, and in intellectualism apologists are criminals.

Our nobility of purpose is what shapes the legacy of our departed and living liberation heroes, and there is no doubt that the vision of just about every independence founding father across Africa was grandiose.

The challenge we have had is that our collective nobility of purpose has not always translated into exemplary leadership.

Perhaps it is encouraging for us that an emerging leadership is fostering a new culture of transparent commitment to duty, like we have seen the Kenyatta administration doing in Kenya at the moment.

The kind of stuff posted by Zimbabwean politicians on social media does not speak well of our politics when juxtaposed with what Uhuru Kenyatta or Alfred Mutua post from Kenya.

It is a tale of bickering politics versus developmental politics, and that is absolutely unnerving.

The catastrophe of bad leadership has created the impression that the African is incapable of finding African solutions to the problems affecting the continent, and this is not exactly a product of racialism or the supremacist attitude of the former colonisers.

We are perennial back-seaters in international affairs because of the indecisiveness and inaction of our leadership.

We believe the world has its leadership somewhere out there in the West, and our leaders compete against each other to impress global powers, even to the point of undermining each other.

Our problem in Africa has not exactly been lack of change in leadership, and many Zimbabweans, Cameroonians and Angolans, would disagree for obvious reasons.

We had the military toppling post-colonial leadership in West Africa in the seventies, and we have had “pro-democracy movements” toppling liberation movements out of power in a number of countries on the continent lately.

However, the military rulers and the pro-democracy movement rulers after them have often disappointed, ending up doing the same things they preach against, even adopting the chart left by the ousted governments.

What clearly came out of the experiments of coalition governments in Kenya and Zimbabwe between 2008 and 2013 was the unequivocal conspiracy for self-aggrandisement across the political divides — crudely expressed by the unanimous resolve for better packages for politicians. The perpetual opposition cries for government austerity suddenly disappeared.

Our erstwhile vocal opposition suddenly turned itself into a conformist lot — fast maturing into the pragmatism of corruption politics.

Even today, our former Prime Ministers is struggling to free himself from the trappings of power — stuck in some state property somewhere where our rich people live, and committedly refusing to yield to the unwarranted pressures of transparency zealots.

Jerry Rawlings is rated well below Kwame Nkrumah in Ghanaian history, not just because he, unlike Nkrumah is not the founding father of Ghanaian independence; but also because the poverty-stricken rural farmers who backed his political rise became absolutely poorer under him than they ever were under Nkrumah. Rawlings just did not deliver on his promises.

Raila Odinga and Morgan Tsvangirai face political oblivion today not exactly because they are just hated politicians.

The two blew their own mythical leadership qualities when they voluntarily chose to be part of government structures in their respective countries, albeit as junior partners to the politicians they had sought to oust from power.

They inadvertently trashed the arbiter of public opinion, drastically squandering huge chunks of their political capital.

Although Rawlings carried out his promise to deal with people he suspected to be involved in corruption, his own post-power indictment did not exclude corruption.

When a country as well endowed agriculturally as Zimbabwe becomes a recipient of food aid, or has its name missing on the global mineral traders list, despite the rich mineral content under its surface, the indictment on the country’s leadership cannot be handsome.

We had Lasch Investments scamming our struggling farmers out of their hard earned little cash in January this year, and it does not look like anything the matter happened to the culprits in terms of the law taking its course.

Lately we have heard of politically connected land barons conning the poorest of the urban poor into paying for illegitimate housing, and again, very little has happened by way of restituting the fleeced masses.

Our land reform and indigenisation programmes could easily be our revolutionary monument as a nation, and perhaps the lasting legacy for President Robert Mugabe, if managed and developed properly.

Some in our leadership is smitten by the demon of individualism, itself the poison that kills every beautiful dream and hope. We have a short-term mentality that has effectively stalled development across the continent.

South Africa’s Black Economic Empowerment (BEE) was meant to get South Africans to acquire nation-building skills, but in all reality the program has only developed a hustler mentality among the few that have benefited from it.

People in South Africa have set up IT firms with no programmers, construction companies with no engineers.

The pre-occupation has been tender acquisition — the use of the black skin to get the gig, only to pass it on to the white supplier, of course after heavily inflating the cost for the job.

Of course South Africa is the land of the legendary Nelson Mandela; that highly honoured man whose indisputable proof of dedication seems to be the time he spent in an apartheid prison, now a national monument.

We have to judge Mandela’s post-prison legacy, not solely by when he relinquished power, but also by what he did with his time at the helm of South Africa’s leadership, especially for the poor majority of South Africans.

On the eve of South Africa’s independence there was need for a type of hero that essentially did not exist, but was desperately needed as part of the terms of handover to the ANC.

The branding policy in the West was to force a rainbow that did not exist, that does not exist even today, and in the political monstrosity of apartheid, a hero was needed — a name and a brand the world could associate with cheek-turning reconciliation, coming hand in glove with Western-style libertarianism and democracy.

Nelson Mandela and Desmond Tutu were instantly elevated to make the grade, and they did not disappoint.

The tradition that created Mandela, and to a lesser extent Desmond Tutu, defines the culture the West is too keen to have Africans adopt.

The tradition is good for Western businesses, and excellent for trade. Needless to say, this tradition is unhelpful to the African cause.

The notion that without Mandela’s rainbow reconciliation South Africa would have had a bloodbath is simply a myth deliberately designed to manufacture fear to justify an agenda, which serves no one else but white elites still controlling and enjoying the privileges that came with the apartheid legacy.

We as Africans must make sure that the name Mandela does not continue to be branded and exploited for the benefit of white imperialism, especially the supremacist residue remnant in South Africa, some of whom in fact own just about all Mandela merchandising, that being the greatest irony ever to happen to the concept of African heroism.

We want to build infrastructure and recover Zimbabwe’s ailing economy, and we must to that effect identify the skill required to achieve this enormous objective.

We have had enough of political dramas to prove the uselessness of our opposition politicians, and most of us are now fully convinced on the uselessness of most of the current opposition parties in Zimbabwe.

But we do not eat political convictions for dinner, and now it is time our leadership delivers on bread and butter issues.

Africa we are one and together we will overcome. It is homeland or death!

- REASON WAFAWAROVA is a political writer based in SYDNEY, Australia.

Comments