Handshakes that define moments in history

President Fidel Castro shakes hands with then US vice-president Richard Nixon in Washington on April 21 1959, during a visit to the US soon after the Cuban revolution. – Getty Images

The Arena With Hildergade

“The handshake is one of the highest forms of symbolic currency with the power to unite, divide, seal deals, and broker peace. It is a simple gesture that can be more informative to people than a whole host of grand speeches. And they dig into our cultural consciousness, staying glued in our memory even if the peace or reconciliation they were supposed to bring about never materialises”

ONE of the most closely watched and analysed personality traits about President Mugabe are his handshakes, be it at the airport, Politburo meetings or his Munhumutapa offices.

Some people seem to have mastered the meaning behind the President’s handshakes and the accompanying body language. The various handshakes that have been published have been defining moments for Zimbabwe’s political landscape.

Such is the nature of important figures’ handshakes and the body language.

The writer looks at two major handshakes between Cuban and the United States of America’s leaders.

These are not ordinary handshakes as they have defined relations between the unfriendly nations – their past, present and future – and how, through those handshakes, they seem to be salvaging the lost five decades of working together mutually and respectfully.

While the first handshake sounded a death knell to the relations, the second resurrected what seemed dead, notwithstanding that it was performed at a funeral service.

After successfully overthrowing the Batista regime, Fidel Castro was sworn in as Prime Minister of Cuba on February 16 1959. Four months later, he visited the US and among the top government officials he met was then vice president Richard Nixon.

According to one report, Fidel instantly “disliked” Nixon.

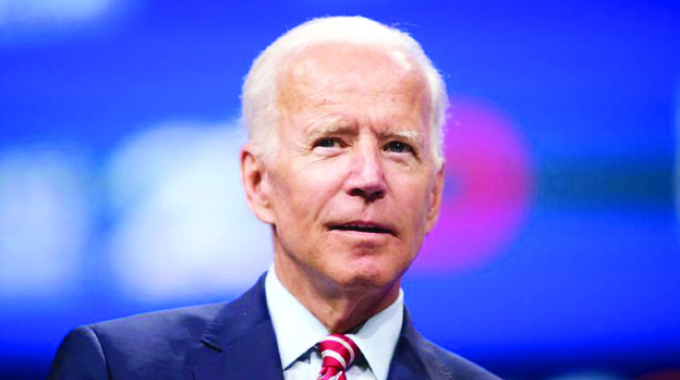

US President Barack Obama shakes hands with Cuban President Raul Castro at a memorial service for Nelson Mandela in South Africa on December 10, 2013. — NBC

The black and white file picture speaks volumes about the nature of relations which would define the two nations, and it is up to the reader to judge who called the shots in the photograph, for Cuba never collapsed since 1959.

According to a press report the writer got courtesy of the Cuban Ambassador Elio Savón Oliva, titled “I did not come to ask for money”, on April 15 1959 Fidel went to the US at the invitation of the Association of Newspaper Publishers and he made it very clear that “Cuba would not beg the US for economic assistance.”

Some of the sentiments he expressed were: “You are used to seeing representatives of other governments come here to ask for money.

“I did not come to do that. I came only to try to reach a better understanding with the American people. We need better relations between Cuba and the US.”

Before departing for Cuba, Fidel met with Nixon.

According to the website history.com, “Nixon hoped that his talk would push Castro ‘in the right direction,’ and away from any radical policies, but he came away from his discussion full of doubt about the possibility of reorienting Castro’s thinking.

Nixon concluded that Castro was ‘either incredibly naive about communism or under communist discipline – my guess is the former.’”

All these sentiments are summarised in the handshake at the press briefing between the 1.91 metres tall former Cuban leader and Nixon (1,80 metres).

This was a defining handshake as it changed the course of history between the neighbouring countries, until President Nelson Mandela’s memorial service on December 10 2013 at FNB Stadium in Johannesburg.

The world witnessed another landmark handshake when Cuban President Raul Castro, who is Fidel’s brother, shook hands with US President Barack Obama.

Speculation was rife whether this signalled the warming up of Cuban/US relations.

Writing in his column Reflections, Fidel congratulated his brother for his “steadfastness and dignity”, when, with a friendly but firm gesture, he greeted the head of the US government and told him in English, “Mr President, I’m Castro.” (The Guardian, UK)

The December 10 handshake paved the way for more handshakes between Presidents Obama and Raul Castro, after the thawing of relations between the US and Cuba.

Re-engagement between the former adversaries has now become a buzzword, confirming Fidel’s 1959 sentiments: “The United States and Cuba have always maintained the closest relations.

There is no reason why these relationships should not be better every day. Our people see the American people with a broad sense of friendship.

At the same time, our people carried the hope for greater understanding by the people of the US for the effort we are making to solve our problems.”

We follow the impact of the 1959, 2013 and 2015 handshakes with interest because they have symbolic meaning, and this is also what it should be in a civilised world.

Joshua Rapp of National Post explains in a 2012 article: “The handshake is one of the highest forms of symbolic currency with the power to unite, divide, seal deals, and broker peace.

It is a simple gesture that can be more informative to people than a whole host of grand speeches.

And they dig into our cultural consciousness, staying glued in our memory even if the peace or reconciliation they were supposed to bring about never materialises, say analysts.”

In the same article, political analyst Chaldeans Mensah says, “Generally speaking, handshakes are routine but they capture a deeper meaning when they occur between adversaries.”

Page Fortna, another analyst, believes that “the handshake is an important part of a process where each party in a conflict ‘slowly becomes, step-by-step, someone acceptable to deal with.’”

Thus handshakes are a unique form of language, a building block for long lasting relationships, including the handshaking that people do at informal occasions.

Comments