First visit to the city feel of ‘civilisation’

Some places in Salisbury were only for Europeans and house servants. You would be arrested for loitering if you were seen in those places

Dr Sekai Nzenza On Wednesday

When the liberation war came, we were sent to live with my brother Charles in Salisbury. My sisters, Charity, Paida and I learnt how to wash our bodies in a bath tub for the first time, how to use a toilet that flushes and how to use a one plate electric stove.

For the first time in her whole life, Mbuya Chizanga was going to Harare, accompanying her sister, Mbuya Gambiza who was visiting the big city for the second time. Mbuya Chizanga is possibly 80 or more years old.

I brought Mbuya Gambiza to Harare for the first time four years ago, when my mother was still alive. My mother said it was time her best friend leaves the village and spends time with us in the city.

“Mbuya, is it true that you have never been to Harare?” I asked. Mbuya Gambiza laughed and said, “Ndichinoitei?” meaning, ‘To do what?’ “I was born muna Save (along the Save River) and grew up there, married off to VaMandiya before I had breasts. I went to Hwedza at Independence to get chitupa (Identification card) and since then, I have lived here.”

Mbuya Gambiza is possibly 86-years- old. Her Identification certificate says she is 65. We all laugh at what is written as her birth date because it was a just a guess. If Mbuya Gambiza lived in Svosve area, when the Land Apportionment Act was passed by the Southern Rhodesia government around 1933, how can she be 65 years old now? She was old enough to walk the journey to the area in the Save River valley called Zone 4 when all her people of the Soko totem were moved from Svosve near Marondera, to make way for European tobacco farmers. The lack of a real birth date is the story of most of our parents and grandparents who were born when there was no birth registry office and they did not vote.

When we were growing up in the village, we longed to go to the big city and see white people, eat ice cream, put our hand in a fridge and see if it comes out frozen, cross a big street without being run over by a car, get on a train, and see a toilet that flushes and experience “civilisation”. But the chance to visit Salisbury never came up until much later.

At one time, some kids from near our village had a competition to climb to the highest branch of a tree and perch themselves up there like a bird. One of them called Jaisoni fell and sustained a very bad fracture. He was taken in a scotch cart to the rural hospital in Hwedza. From Hwedza they said he needed a big operation in Salisbury because the fracture was an unusual one.

Jaisoni stayed at Harare Hospital for a long time. When he came back, he wore new clothes and had plenty of toys. We gathered around him as he told us about his experiences in the hospital. He said every day, white doctors, and maybe one black one among them came to surround his bed and talk about his fracture. The old white doctor pointed at X-rays, teaching young students about the fracture. All the European young student doctors smiled at him. One of them, a young lady, brought him a drawing book and taught him to speak a few English words.

For some time, Jaisoni was a hero in the village homestead and at school. A few weeks later, another kid from down the Save River valley, climbed the highest branch and deliberately fell from the tree, hoping to sustain a leg fracture so he could also go to Harare Hospital and get gifts. He got a broken hand and went to Hwedza Hospital for a plaster. Headmaster Muchando then gave a warning that we should not tempt the ancestors by falling deliberately off trees so we could visit a hospital in the big city. We could sustain a head injury and die.

Although there was always an excitement of the unknown when we thought about the big city, we also felt a sense of fear. There were many scary stories told about how people disappeared over there.

There was the story about Mai Kesipa, our muzukuru, the one renowned for her lisp. Her husband, Lancelot worked at David Whitehead, the cloth factory. Most of our relatives worked there. Lancelot did not come home for more than five years. Mai Kesipa travelled on the village bus to Mbare Musika to look for her husband. Samuriwo the bus conductor said he would find someone at Mbare who could show her where her Lancelot lived.

At Mbare Musika, Samuriwo failed to find anyone from our village. Since the bus could not stay in the rank for too long, Samuriwo left Mai Kesipa at the place where people from our village usually met. He said, if she stayed there long enough, someone was bound to arrive and take her to Lancelot’s lodge in Matapi. After all, Matapi flats were just across the road from the market.

Mai Kesipa sat on the pavement, breast fed her baby and ate a meat pie for the first time. She sat there for hours watching people from all over Zimbabwe move around the market, selling or simply rushing to catch a bus to their villages. But Mai Kesipa did not see anyone from our village.

When it was getting dark, she started crying. A man offered to take her home for the night, but Mai Kesipa said no. She recalled that back in the village, they talked about strange men who appeared to be very kind and they took women home and forced them to do what the women did not want to do.

A kind woman took her to the Municipal office guards. They said every day someone was bound to be lost at Mbare Market. They had a big loudspeaker for announcements of lost relatives.

The loudspeaker shouted that there was Kerisitina Magondo, wife of Lancelot from Matarutse village, under Chief Tambaoga, in Charter District who was looking for her husband Lancelot Magondo or her uncle, Cephas Mashiri Nzenza. If anyone knew these people, please come to Matapi loudspeaker near the police station.

One of our relatives called Gurura was enjoying a beer at Mapeticoat Bar when he heard the loudspeaker. He quickly found Babamunini Cephas who was in another bar and they went to pick up Mai Kesipa and delivered her to Lancelot.

Back in the village, people said, the ancestors were very kind and protective to Mai Kesipa. She could have been taken by migrant men from Mozambique, Malawi or Zambia. These men came to Rhodesia without wives and they did not mind falling in love with a woman they had only just met. Mai Kesipa also said she was lucky. For the next 20 years, she did not visit the city at all.

When the liberation war came, we were sent to live with my brother Charles in Salisbury. My sisters, Charity, Paida and I learnt how to wash our bodies in a bath tub for the first time, how to use a toilet that flushes and how to use a one plate electric stove.

We took pride in cooking meat, vegetables and sadza on the stove without burning the food. At first, cooking sadza was hard because one of us had to hold the handle, while the other stirred vigorously the same way we used to cook sadza on the village fireplace.

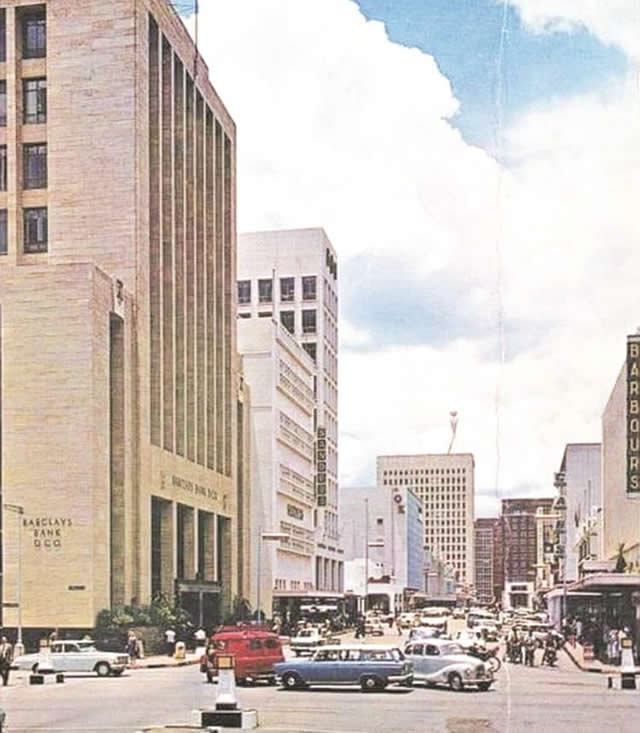

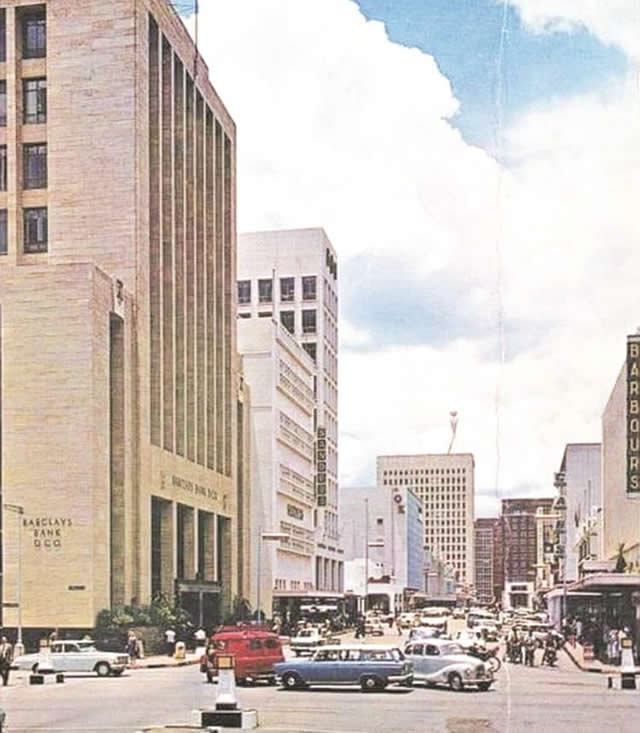

Our orientation to living in the city was a long one. We did not dare travel to the city centre on the bus, for fear of getting lost. Our knowledge of Salisbury was limited to Highfield, Glen Norah and Mufakose. Relatives working as gardeners and maids told us that there were big suburbs like Borrowdale, Mt Pleasant, Highlands and others. But those places were only for Europeans and house servants. You would be arrested for loitering if you were seen in those places.

Mbuya Gambiza and Mbuya Chizanga arrived in Harare to stay with me last week. As we drove along Julius Nyerere way, the two vanaMbuya, spoke to each other with excitement. “The little cars, have no respect for big ones. They rush past them!” said Mbuya Gambiza. “And when they see the big light go red, they obey and all stop. When the light goes green they race each other again!”

I recalled my own life when I first came to Harare, then Salisbury, and laughed at myself, reminiscing on how much has changed since the days we lived in the village and knew nothing about the world of electricity, tap water and television. And now we take all that as a natural way of life. But some of our village relatives still dream of visiting the city and seeing the lights of our so-called civilisation.

Dr Sekai Nzenza is a writer and cultural critic.

Comments