Factionalism a reality that cannot be ignored

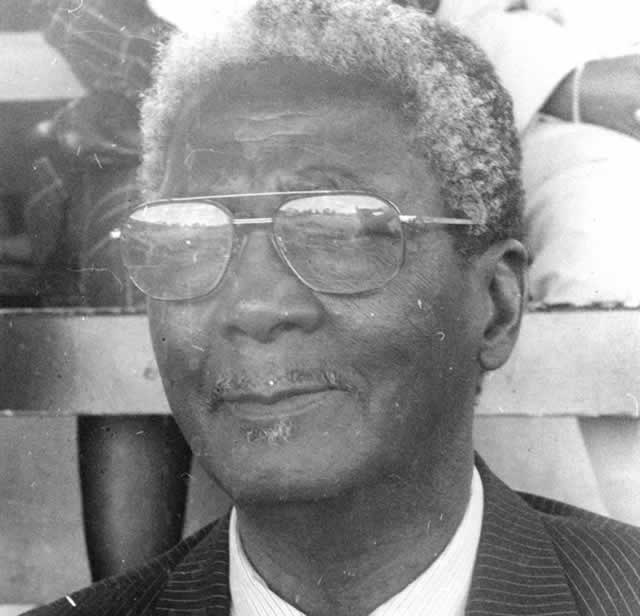

Reason Wafawarova on Thursday

Reason Wafawarova on Thursday

There is no doubt that factionalism has a bearing on the stability of political parties, on the parties’ general institutionalisation processes, on their efficiency, as well as on their legitimacy in the eyes of the voters or any other observers.

IN a 2005 journal titled “Factionalism and Political Parties,” German scholars Patrick Kollner and Matthias Basedau gave an incisive outline of the reality of intra-party groups within political parties, otherwise commonly referred to as factions.

There is no doubt that factionalism has a bearing on the stability of political parties, on the parties’ general institutionalisation processes, on their efficiency, as well as on their legitimacy in the eyes of the voters or any other observers.

We cannot overemphasise the fact that political parties are by their very nature central to the concept of democratic institutions, and also a key factor in attaining democracy itself. While political parties mirror any other formal organisation in that they have formal organisational structures, norms and operational structures, it must be noted that they also have informal relational systems, sometimes strong enough to determine the course of policy direction within the parties.

In Africa it is hard to assume that formal structures and rules within political parties form the binding framework for all concerned, or that intra-party processes will take place within the constitutional confines of the declared party framework.

Managed by power-loving politicians, political parties are not homogeneous organisations that are certain in terms of the goals they pursue, and neither are they necessarily bound by some sort of unitary will.

Essentially political parties are products of coalitions of selfish political actors with individual ambitions, interests and goals. In Zimbabwe we had the MDC formed in 1999 as a coalition of workers, disgruntled and dispossessed Rhodesians, frustrated students, donor motivated civic groups, intellectuals, and support-seeking minority leftist groups like the International Socialist Organisation (ISO).

Even Zanu-PF at its formation had rightwing liberalists, socialists, hardcore communists, intellectuals, nationalists and trigger-motivated adventurous youths coming together to push the independence war effort into fruition.

In general politics can be seen as a process based on the conflictive and consensus-oriented relations among interdependent individuals, and likewise intra-party politics are characterised by conflict and consensus between interdependent groups within political parties (Moshe Maor 1997).

As we see with the intricate decision making process within Zimbabwe’s political parties, factions can influence the internal decision making process of any party, and Robert Hamel and Alexander Tan make a good argument of this in the journal “Party Actors and Party Change: Does Factional Dominance Matter?”

While we have gotten used to incessant denials of factionalism by leaders of political parties that are evidently afflicted by this scourge, it must be noted that it is quite dangerous to regard factionalism as ephemeral, short-lived and unimportant, and certainly the phenomenon is not ignorable.

We just need to see what has happened with the yesteryear rumour of the Biti-Chamisa-Tsvangirai factions within the MDC-T, itself a factional offshoot of the original MDC formed in 1999. We have witnessed a prodigious disintegration of what used to be a formidable opposition political party.

The cohesion and competition within a political party can entirely depend on what factions within the party do, and the ZANU-PF chaotic 2013 internal elections for provincial executives stand as a good example of how factions can override merit and fairness in the pursuit of the interests of factional leaders. Now we are in the run up to the party’s elective Congress at the end of the year, and more and more factional shenanigans are hitting newspaper headlines.

We saw the impact of factionalism on electoral systems in 2008, when one notorious ZANU-PF faction played spoiler to the party’s winning prospects, just falling short of giving the MDC formations an outright victory enough to dismiss the revolutionary party from power, with Morgan Tsvangirai missing the mark by a mere 2 percentage points. The same faction reportedly joined the MDC formations in resisting the occurrence of the July 31 2013 election, albeit unsuccessfully. Factionalism can affect a political party’s state and societal functions, and ZANU-PF’s Zim-Asset economic blueprint has been no exception.

Factions are dissensions within a group, or a group or combination of people acting together within and usually against another group within a larger body, in our particular case a political party. Even churches and corporations do have factions as well.

The positives of factions include the fact that they can progressively break ranks with retrogressive traditional patterns of political behaviour, like the culture of impunity protecting errant veteran leaders from accountability. Factions arise essentially because some people within political parties will be struggling for power, and as such factions normally advance the ambitions of particular persons, and sometimes they do advance specific policies or ideology. Normally factions represent party divisions based on personal interests of factional players, not on principles.

Factions comprise both politicians and voters, and if unchecked they can grow to overshadow the parent party that host them. It is easy to trace a common identity, common purpose and collective action in the conduct and behaviour of factional players. We read some time ago ZANU-PF’s Temba Mliswa bragging about his factional membership before a legion of journalists, and he made his point very clear on what he believed factional politics were doing with the public media.

Factional members generally band together under the label of a defined tendency, and we have heard many times of two factions within ZANU-PF, one of reported hard-liners and the other of so-called moderates. Last Saturday we read in this paper an article lambasting the behaviour of some of the purported moderates, one for sanitising with undeserved dignity the ungrounded claims that last year’s elections were “stolen,” and the other for playing the moralistic apologist to a section of our white community.

Factions can develop a strong organisational backbone, and this is particularly worrisome when it happens within the context of personalised factions. These are factions based on clientelism, itself the central mechanism for mobilisation.

In personalised factions the chain of command is vertical, all leading to one person – the factional leader. Any horizontal links within such factions are treated as treacherous, and to make sure that the hierarchy is not ignored, the faction is usually named after the leader, like MDC-Tsvangirai. This is vital to the identity of the group. Even the current ZANU-PF factions are named after two senior politicians within the party; at least by our media.

In 2011 this writer had occasion to watch ZANU-PF’s organising man in action, two mobile phones incessantly ringing one every two minutes or so, and the man was barking orders on how to phase out contesting members of one faction from the provincial party structures across the country. My visit had been necessitated by some personal need for assistance, and I hardly got any attention as the man switched from one mobile to the other dishing out unkind instructions to some dirty-sounding foot soldiers on the ground. “Make sure none of their people finds a way into the new structures,” went one of the instructions.

Our political parties have been smitten by elite factionalism, open factionalism and other factional alliances, and there is no denial on the impact this has had on our political landscape.

Positively factionalism kills apathy and creates interest in the politics of our country, and this can be good. Sometimes factionalism can even further a good principle, and of course factions do provide a sense of belonging to their members. It can also be argued that factions can promote generational change, and Zimbabwe is one nation where an entire generation has struggled so badly to make a meaningful contribution to the politics of the country.

Let us look at some of the negative consequences of factionalism. Factionalism can make party management an insurmountable challenge, and one can look at the bickering among our politicians across the political divide to see this.

As earlier mentioned factions can undermine cohesion and effectiveness of political parties, and we have heard President Mugabe publicly lamenting the effects of factionalism in relation to succession aspirants within Zanu-PF. In the worst case scenario factionalism can lead to splits and disintegration, and we have seen the MDC splintering into at least five rival groups since 2005.

One major negative consequence of factionalism is mediocrity caused by factional affiliation overriding merit in the election of office holders. Factional leaders are more worried about loyalty than they are about merit in choosing their allies. It must also be noted that faction based dissent can reduce or destroy a party’s ability to mobilise and recruit new members, and one can look at the by election vote results across the country and how the MDC formations have been faring so badly since the ugly split earlier in the year. As earlier said, factional squabbles can destroy the ability to organise and campaign for the vote, and we saw that with Zanu-PF in 2008. The predicament led to a forced coalition with the MDC – itself another negative consequence of factionalism.

Factionalism can lead to blurry and contradictory policy positions within a party, and we have seen senior Zanu-PF politicians contradicting each other over the indigenisation policy, and lately over ongoing inquiries on media polarity.

Factionalism can also impede intra-party discussions, and issue-oriented debate can easily degenerate into the whirlpool of inter-factional power struggles. At its worst factionalism can be responsible for unaccountability, impunity and corruption, and at one time we had reports that one faction was against the anti-corruption drive, and that in the name of protecting and preserving the party Zanu-PF.

Generally, factionalism can easily weaken the moral standing, authority and integrity of a political party, and we can look at the waning fortunes of the MDC to see this. What we have seen in this case is near total destabilisation of a party system, and this can lead to voter cynicism, as results of by elections so far held clearly show.

Of course there are positive consequences of factionalism. Kollner and Basedau assert that factionalism can be a transition belt for bargaining processes, conflict resolution, and even consensus building within political parties.

They also argue that factionalism can help to increase political participation and activism, can also help to increase mobilisation and recruitment of new members, and can help strengthen the inclusionary character of a party.

In a way factionalism can actually result in stability a party’s leadership, promote a sense of unity if the basic ideology of the party is not brought into question.

Perhaps ZANU-PF’s landslide victory in election 2013 could be attributed to this unity around the basic ideology of the party – generally centred on mass emancipation policies.

Factionalism increases debate and competition between people within a party, and that is healthy and positive. It can also be argued that factionalism can have a moderating effect on the party, and we have already talked about moderates and hardliners as reported on the part of Zanu-PF.

As a political phenomenon factionalism can be ambivalent, yielding very destructive and constructive consequences at the same time. While factionalism can help mobilise voterss and even win elections, it can immensely diminish the winning party’s ability to govern effectively.

Competing factions within the ruling party are hardly complementing each other on matters of national governance, and that is a tragedy for the country.

As Tendai Biti and his colleagues would argue, factionalism can be conducive for renewal, but the larger picture is that factionalism within the MDC-T has resulted in a dysfunctional political structure, and one can easily trace down the sclerosis in the opposition party to the evils of factionalism.

The nefarious denials of factionalism by our politicians are neither a sound political strategy nor an honourable thing. Factionalism is a reality we cannot wish away, and the sooner we deal with it like a reality the better it is for the unclear future of the country.

Zimbabwe we are one and together we will overcome. It is homeland or death!!

REASON WAFAWAROVA is a political writer based in SYDNEY, Australia

Comments