Echoes of transformation as ‘painbrush’ pokes fun

Hildegarde The Arena

TODAY the people of South Africa commemorate the 23rd anniversary of their Freedom Day, for it was on April 27, 1994 that universal suffrage was enjoyed by all South Africans regardless of race, colour, creed, religion, gender and social standing.

It ushered in a democratic dispensation in one of Africa’s largest, but stratified and racialised economies.

The commemorations are taking place during the centenary celebrations of Oliver Tambo, the African National Congress’ longest serving president, and there is a clarion call upon ANC cadres and all South Africans to “deepen unity of purpose during this period and beyond”, for Tambo was the visionary of a future that others believe is a mirage.

The day is also described by some as fractious – a watershed moment in the youthful democracy, as there are street protests galore.

If media reports are anything to go by, including direct pronouncements from the ruling ANC government, thus today South Africans remember this important day as a very polarised society, a society that cannot come to terms with itself, a society that believes that the elasticity of freedom of expression and association should mean they squander precious time protesting, or getting in and out of courts.

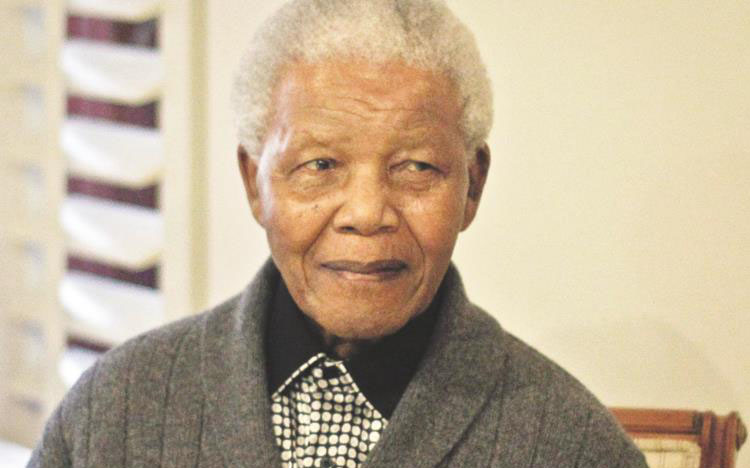

They have failed to decipher Mandela’s long walk to freedom in order for them to face the realities of making their own history and how that history gives birth to a future, and so on, and so forth. We give them time to find each other unless, of course, they want to reverse the gains of 1994.

Meanwhile, President Jacob Zuma is under attack from various quarters, but his government and the ANC have resolved that there is no going back on the radical economic transformation they mooted at the Mangaung Conference in 2012.

The president and his lieutenants are resolute that they will right the wrongs of the past, especially equitable distribution of the economy, in its widest forms and interpretations. They argue that this is not rhetoric or sloganeering, but there will be deliverables.

To buttress this is a paper published by SAnews.gov.za which states: “One of the key features of the 2017 State of the Nation Address (SONA) has no doubt been the government’s intended stance to ‘radically’ transform the economy and ensure equitable share of the country’s wealth.”

The reason being that “more than 22 years after South Africa attained its democracy, it has become clear that economic exclusion remains a stubborn reality despite two decades of political change. Changing the face of the South African economy, which has benefited a few for decades if not centuries, was not going to be easy to achieve in a space of 22 years,” the statement reads.

It adds: “Evidently . . . , the South African government is growing impatient with the slow pace of economic transformation, a tragic phenomenon that has left the majority of black people trapped in a mud of poverty and economically disempowered,” while President Zuma says “political freedom alone is incomplete without economic emancipation”.

Deputy President Cyril Ramaphosa also weighed in, telling cynics they better wake up and smell the coffee because “transformation will only be achieved when all South Africans are able to share in the country’s wealth as per the Freedom Charter”.

He recently heightened his pitch when he presented a paper at the Black Business Council titled: “Radical economic transformation should be about building a more equal society.”

Although not exhaustive, he made the following notable points:

1. “We must be honest enough to admit the depth of the political, economic and social challenges our country faces. And we must be courageous enough to recognise the domestic and global conditions that give rise to these challenges.”

2. “They (the black people) desire training opportunities and want to work. They want access to land and the means to productively farm it. They want to own factories and start enterprises to employ others. To fail them would be a betrayal of their confidence and a dereliction of our responsibility towards the constitution.”

3. “This is a time to prioritise the cries of the marginalised and the poor through policies and actions that promote sustainable and inclusive economic growth, effective redistributive measures and ethical management of public resources.” (Source: Daily Maverick/Internet)

In a recent radio interview, Zweli Mkhize, the ANC treasurer-general, showed how serious the ANC government was when he said “land and the delay in land redistribution in the context of ‘radical economic transformation’” will be up for discussion at elective conference to be held at the end of the year.

As South Africa prepares to chart its way into unknown territories, what is evident is that it will face stiff resistance from the small minority white group that controls a large chunk of the economy.

For example, columnist Max du Preez, expressing views held by his kith and kin and black sympathisers, argues that the route being taken by South Africa is a “historic mistake”. Wrote Du Preez on April 25: “Proponents of the mantra of ‘radical economic empowerment’ have found a new argument to the question whether it would destroy the South African economy as has happened in Venezuela and Zimbabwe: black South Africans might suffer for a while, but they will then rise as fully empowered and in charge of the economy. It is a seductive but false and dangerous argument.”

The white capital monopoly narrative would be incomplete without some cynics making Zimbabwe their case analysis.

Du Preez and his ilk know that the land issue is a ticking time bomb. The Black 1st Land 1st movement, whose membership is from the millennial generation, wrote on its Twitter handle two days ago: “For a colonised people the most essential value, because it’s the most concrete, is first and foremost the land – the land which will brings them bread, and above all, dignity. The resolution of the land question is central to the realisation of the black liberation project.” Charira-a!

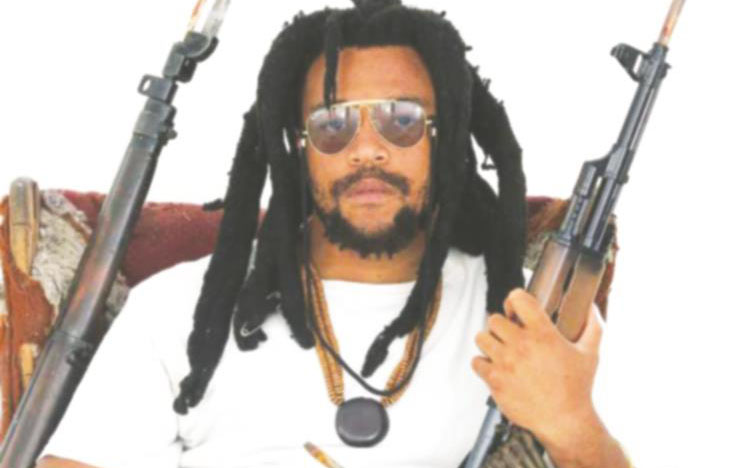

But, it is the artistic perspective in this matrix that gives the feeling that the “painbrush” (paintbrush) is being used to fire the real salvos, especially when it is used by artists with whose fixation centres on hate and denigration of black men’s manhood.

No doubt, art is an important vehicle of communication whose meaning is embedded in historical, social, cultural, religious, scientific, economic and sexuality registers (homosexuality included), but is there in art something that resembles integrity and moral values?

Do artists use their paintbrushes (“painbrushes”), ink and canvas as symbols of power, influence and manipulation, in which case they are no different from the people they ridicule?

Controversial artists Jonathan “Zapiro” Shapiro and Ayanda Mabulu’s latest paintings parodying Presidents Zuma and Mandela have been roundly rubbished as grotesque, unpalatable and way overboard even within the confines of freedom of expression as prescribed by the South African Constitution.

The ANC voiced its concerns saying, “Ayanda Mabulu’s new artwork is ‘grotesque, inflammatory and of bad taste’. No matter what message he may want to send to President Jacob Zuma and the African National Congress, we view his work as crossing the bounds of rationality to degradation, exploiting the craft of creative art for nefarious ends”, the ANC’s Khusela Sangoni said.

Surprisingly, writer Ralph Mathekga, just like the artists, presented an even more radical opinion on the issue arguing that the Zuma/Mandela piece by Mabulu was finally “re-politicising” Mandela and “piercing the veil of sainthood that Madiba has been clothed with since his retirement from politics as the president”.

In his News24 piece, Mathekga writes: “South Africans would go to great lengths in depoliticising Madiba, and Mabulu is having none of that. For him, South African politics is vulgar and Madiba has to be brought into this new normalcy of vulgarity of political intolerance and open corruption.

“Mabulu’s depiction is very explicit and outright offensive. But so are corruption and the current degeneration in our society . . . We need to bring Madiba back into our politics, and we should do it not in a superficial sainthood manner, but in a more practical way, as Mabulu has. As for the idea that Mabulu is a porn artist; our politics is just as vulgar and hardcore.”

Mabulu and Zapiro remain defiant about their artworks with the former arguing: “There are no boundaries. Nelson Mandela himself is not God. He is not the Messiah and he understood that himself. We‚ the people‚ are the Messiah.”

In some form of double-speak on the rapist metaphor, he added: “All the people who died before 1994 died in vain. They must be turning in their graves today when they see the oppressor‚ the rapist doing what he does. He is constantly molesting this country.”

Zapiro says for him, the violent rape symbol is the most poignant: “I know that it’s shocking. People have said why use the rape. I am using it because it is shocking, but I think that you can see‚ any viewer can see the empathy that would be generated by this cartoon for the person who is being raped.” (Source: Times Live)

Some analysts argue that all this is done for personal aggrandisement, fame and fortune.

Whatever the case, the growing chasm among South Africans needs to be acknowledged and dealt with as soon as possible. Failure to do so would result in throwing the baby out with the bath water.

Comments