Discussions, debates on decolonising the African university

Christopher Farai Charamba : Correspondent

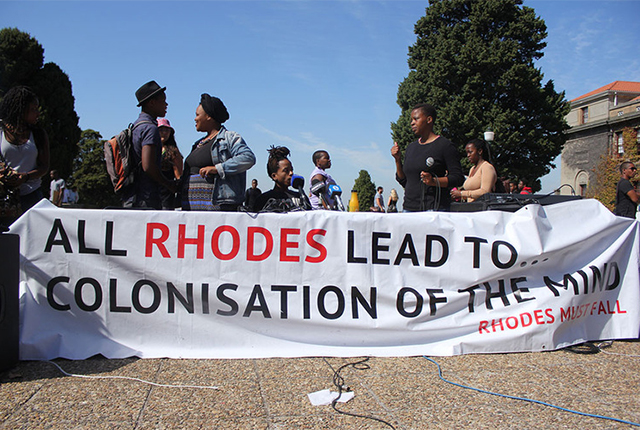

A couple of weeks ago the University of South Africa (UNISA) hosted a conference on Decolonising the University in Africa. The subject of decoloniality has come to the fore in recent times following the #RhodesMustFall movement at the University of Cape Town, #Luister at Stellenbosch and #FeesMustFall at other universities in South Africa.

Many of these traditionally white universities such as Rhodes, UCT, Wits and Stellenbosch have been accused of perpetuating white paternalism and institutional racism. The discussion on decolonising the university in Africa is taking place as a means to correct prejudice at institutions of higher learning.

Aside from decolonising the space of universities by the removal of statues and the renaming of buildings, there have also been questions about decolonising the curriculum and the education system as a whole.

The conference at UNISA covered a number of subjects of an interdisciplinary nature. Issues discussed included but were not limited to; decolonisation of space and architecture, decolonising gender/feminism, decolonisation of knowledge, shifting the geography of reason and indigenous knowledge systems.

Latin American decoloniality scholar, Professor Ramon Grosfoguel, opened the conference with a keynote address on “Decolonising the Curriculum: Some suggestions for the sciences.”

In his address he posited that in the Westernised university, which is the system most universities around the world follow, “epistemologies are racist and sexist.” Professor Grosfoguel made the point that universities privilege white men from five Western countries namely; France, Germany, Britain, USA and Italy.

“The names change across time and courses but the nationalities remain the same. When we talk about decoloniality we need to decolonise the foundations of these epistemologies,” he said.

Prof Grosfoguel argued that the problems that the university in Africa faces stem from the fact that what is considered knowledge and what is taught are based on the epistemologies of the men from the five Western countries.

He added that these men had managed to become the authorities on knowledge through genocide, epistemicide, which is the killing of knowledge and epistemic extractivism and appropriation over the long 16th Century.

“We have to raise the historical awareness as to how the Western university has managed to be captured by the knowledge of these white men from five countries. This took place in the 16th Century under four genocides/epistemicides.

“The first was the European colonial expansion, the conquest of Al-Andalus and the genocide against Muslims and Jews. The second was the conquest of the Americas, the third against Africans, beginning with Portuguese expansion and then finally the fourth being the burning alive of women in Europe who were accused of being witches,” he said.

Prof Grosfoguel stated that by the time Descartes said “I think, therefore I am”, the I he was referring to was a European white man. All other races and women had been excluded from the narrative on the production of knowledge as this had been colonised by the Western man.

He went on to argue that universities in Africa “need to move from a university, one that decides what is knowledge, what is truth and what is good, to a pluriversity. We are throwing away knowledge by going to five countries.

“We need for colonies of knowledge to understand the problems and produce a pluriverse of knowledge.”

In one of the sessions that dealt specifically with the #RhodesMustFall and Student Movements, Dineo Makgakge of Rhodes University presented a paper on “Decolonising the Curriculum within Higher South African Universities”.

“In terms of curriculum, the subject of decolonisation requires change in our teaching practices and in the course material we teach,” she said.

Makgakge argued that the #RhodesMustFall movement highlighted the challenges in South African academia as well as the divisions within the curricula.

“Scholars such as Mbembe conclude that we do not have African universities in Africa, but merely masquerades of Oxford and Cambridge . . .

“Colonialism and imperialism influences were evident in order to enforce the concession of education for the African child,” she said.

Advocating for indigenous knowledge systems to be included in the curriculum, Makgakge said, “The proxies of decolonising the curriculum should be shared across the practices and inclusivity of the African knowledge system, which has been in existence for many years.”

Mmaphuti Langa from the University of Limpopo contributed to the discussion on decolonising the university by focusing on “What role can students play in Decolonising South Africa?”

She argued that for a long time the youth have been drivers for decolonial change, be it during the liberation struggles, the Arab spring or more recently in the #RhodesMustFall movement.

“Decolonisation is long, lengthy and exhausting. The role of the students is to keep the conversation going and involve as many students as possible.

“Student movements are formed to bring about social, political or economic change. With regards to decolonisation, it can only happen when people move from a state of blindness. The #RhodesMustFall movement brought students out of a state of blindness,” she said.

Wits University scholar, William Mpofu spoke on the “Pitfalls to Decolonial Consciousness”. In his argument inspired by Frantz Fanon, he argued that “decoloniality needs to be protected from decolonial thinkers.”

According to Mpofu, there is the risk, as Fanon posited, that the decolonial process could suffer a similar fate to nationalism which originated as a unifying force but descended into a divisive force. This degeneration is blamed on intellectual laziness of the political and economic elite.

“Pitfalls mean tendencies within decolonial school to invent tables, ethnicities and circulate fictions which narrow rather than expand. In such an instance, coloniality takes over using the name of decoloniality,” he said.

Mpofu argued that transformation in the decolonial process should not be hostage to revenge but should lead to liberation.

“It is the responsibility of the oppressed to liberate themselves as well as the oppressor,” he said.

Following on from this, Mpofu posited that it was important for decolonial thinkers to be rigorous in their processes as the colonial processes are well established and particularly rigorous themselves.

One of the more controversial presentations was from Unisa professor, Everisto Benyera who argued, “Why University transformation was the wrong agenda.”

Professor Benyera began by stating that “we are colonised and apartheid is still with us.” He went on to question how many problems academics had solved and said this group of people tends to be reactive rather than proactive.

“We face a colonial system which constantly reinvents itself. Colonialism is now institutional,” he said. Professor Benyera argued that major world institutions in various fields such as health, banking or trade, the World Health Organisation, the World Bank and the World Trade Organisation are dominated by former colonial powers.

“Sometimes we think we are thinking decolonialism but we are thinking through a colonised mind. We are using a colonised mind to decolonise itself.

“This is evident for example by the fact that we were stealing Karl Marx’s solutions for his time and his situation and applying them to ours,” he said.

What was evident from the conference is that the subject of decolonisation is a complex one with many different facets and ideas.

The process is not a homogeneous one and needs multiple approaches to decolonise not only the African university but also knowledge as a whole.

Key for this to be achieved however, is the need for scholars to leave their ivory towers of academic conferences and work directly with policy makers to bring their theories and suggestions from the abstract to reality.

Feedback: [email protected]

Comments