Cut us, we want babies

Roselyne Sachiti Features Editor—

. . . genital mutilation for desperate infertile women

Tuesday September 27, 2016 marked eight years since Muyeye Munkuli (33) of Sinamusanga area, Binga in Zimbabwe’s Matabeleland North Province, married her husband Luke under customary law.They have been together through life’s ups that include traditional weddings, huge harvests and downs that include droughts and food insecurity, loss of family members to death. Yet, the couple’s biggest challenge to date has been failure to conceive. No medical examinations to determine who between husband and wife is infertile have been carried out. Instead, the burden to try to conceive has been on Muyeye.

Society also expects her to give birth to as many children as possible to preserve family lineage.

Under intense family pressure, she sought the services of a local traditional healer in January last year. After a “thorough” examination that included pressing her pelvic area to feel her uterus and also inserting her fingers in her private parts, the healer told her she had some foreign flesh in her private parts which blocked her husband’s semen from moving up to her ovaries to allow fertilisation.

Commonly known as “sare”, the issue is not openly spoken about in many Zimbabwean cultures. Sare comes in forms that include male known as ‘gono’ or the female known as ‘hadzi.’

“I was more scared of how my mother in law would react upon hearing this news. If anything, my husband’s family was already blaming me for failing to bear them grandchildren. I cried all the time until I heard of elderly women who have helped many other women in this area. I visited one who said she would help me conceive but I had to go through a procedure. She said I had the gono sare and gave me herbs to take before the procedure to avoid complications,” said Muyeye.

She was told to return two days after taking the medicine and she complied. She was also told to bring a new razor blade.

“I went back and was told that the woman would cut off the sare. She said it would cause some serious discomfort but I would heal quickly. I was desperate for a baby and would do anything to have one,” she said.

The pain was excruciating. She bled. More blood gushed out. And yet, the woman kept cutting off the “excess” flesh which did not belong in her private parts. Her mother-in-law, desperate for grandchildren, held Muyeye down, comforting her to be strong.

“I stopped crying when the process ended after 10 minutes. The blood that came out could have filled a one litre container. I felt weak afterwards and struggled to get home. I did not know what to tell my husband so I pretended that my period had started. At least this helped me explain the blood and also nurse my wound. It’s a secret I kept with my mother-in-law,” she added.

Conjugal rights

In days that followed, another problem emerged. Her husband wanted to enjoy his conjugal rights and demanding sex.

“It was impossible to have sex after the bleeding stopped. The wounds would not heal. My husband suspected something was wrong. I tried to make him use a condom and he refused. He said I should confess if I had a sexually transmitted disease. He asked me why a married woman should ask to use a condom,” she said.

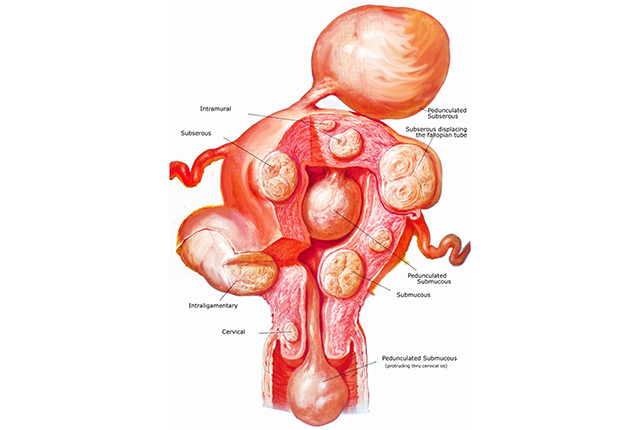

She went to their local clinic where nurses said the wound had become septic. They also referred her to their main hospital where a scan of her uterus was taken and doctors found that she had multiple uterine fibroids, some measuring eight centimetres with the smallest three.

“They said I should undergo an operation and I did so after three months. I fell pregnant in September that year,” she said.

Nduleto’s hell

Her experience was better. For women like Nduleto Nyathi (26) of Kariangwe, 80 kilometres from Binga Centre, it was like a chapter from a hellish movie. She was also referred to a healer who would help her conceive.

“I tried to conceive for three years and failed. My husband had two other children from a previous marriage so the blame was automatically placed on me. This took a toll on my mental health as I tried to understand why things could not just happen. I heard of a woman who helped barren couples conceive so I visited her,” she said.

At the shrine, she was told to bring a small bucket, cotton wool, coarse salt, soap and razor blade. She was also given “holy” water to bath in and also drink before the procedure would take place.

“I followed the instructions and went back. She inserted her fingers in my privates pulling out what she said was the male sare, which caused me to be infertile. She said the flesh blocked my cervix and this was a sign of evil. She cut off some of the flesh and I bled. She removed three more bits of flesh and by that time I was bleeding more and becoming weaker. I passed out and regained consciousness moments later,” she said.

Panicking, the faith healer used her donkey drawn cart which took her to the hospital. The journey was long as it had rained the previous night and roads were difficult to navigate.

“We eventually got to the hospital and I was immediately attended to. It was a horrific experience, I almost died. My husband has stopped pushing for a baby ever since the experience. We will wait for God’s time,” she added.

Some like Selina Muzamba have not been so lucky. She haemorrhaged and died at home on September 8 last year, three days after the “operation” to remove her sare was conducted by her grandmother.

Faith

But there are some like Chimuka Muleya (33) of Siakobvu area who have faith in this method. They say though painful, it has worked for them.

“It was painful but I went through it because of determination. I did not lose a lot of blood as my sare were smaller. I would wash my wounds with salt water and some herbs. I fell pregnant three months later,” she said.

Health condition evil?

This procedure is also being practiced in other parts of Zimbabwe. In Harare’s, Epworth area, Madzimai Brenda from the Johanne Masowe apostolic faith has been also carrying out this procedure to help women conceive. She says sare is a sign of evil and should not be part of a woman’s vaginal anatomy.

“It blocks the fertilisation path. It should be removed through prayer. We first give a woman holy water to drink and also use when washing her private parts. If the sare does not disappear, we then ask the woman to bring a razor blade, soap, cotton wool and a bucket. We cut off the excess flesh and usually women we have helped heal in a few days,” she said.

She added that she has helped clients both affluent and poor adding that only the strong ones have made it through.

“This procedure is not for the weak. Some women cry and tell you to stop when you make the first incision,” she said.

She said she got her training from her mother and other “midwives” in their church.

“I was only 10 when I started seeing my mother help many women through this procedure. I would watch her do it and when I turned 18 she taught me. I would assist her with the procedure and now I can say I am good, even better than her,” she added.

In Mbare, Harare, another woman, Madzimai Stella, also performs the procedure especially on women who have failed to conceive over a long period of time. She says in a month, she helps up to five women and none of her clients have died.

“I help women who fail to conceive. Sare makes women infertile. In some cases where women manage to fall pregnant, they usually miscarry. If they carry the pregnancy through, the baby dies usually a few hours after being born or before they reach three months especially if the sare comes in contact with the baby’s fontanel. That is why it is important to remove the sare from all women who have it,” she added.

Removal of sare is a form of genital mutilation many women go through. While in some customs women go through various forms of forced genital mutilation, those seeking fertility find themselves volunteering their bodies for the procedure to protect their marriages. With long waiting periods for procedures like myomectomy in public hospitals many poor women end up opting for backyard removal of fibroids. Myomectomy is the surgical removal of fibroids from the uterus. It allows the uterus to be left in place and, for some women, makes pregnancy more likely than before.

A myomectomy costs about $400 in a government hospital where waiting periods for the procedure are longer. Fees charged by private gynaecologists are also out of the reach of many poor women with the condition. A private gynaecologist will charge about $1 500 for the same procedure.

The biggest problem?

Zimbabwe National Practitioners’ Association President Sekuru Friday Chisanyo said the biggest challenge today is that most people cutting sare are inexperienced and take shortcuts.

He said traditionally the matriarchs that include aunts and grannies would check teenage girls’ vaginal anatomy to see if there was anything foreign.

“They just did not carry out virginity tests as some people may think, they did many other good things. If they found out that teenage girls had sare, they would start giving them herbs to shrink them. This was a good intervention as the girls would be cured before getting married,” he said.

He said there seems to be an increase in women having sare because the prevention measures of yesteryear are no longer being implemented.

“Most women find out they have them when they fail to conceive, have miscarriages, still births or when their husbands complain that they feel something foreign in their private parts. Sare is being identified at a later stage and this has also caused a lot of conflict in many families as people trade witchcraft accusations,” he added.

How it was done yesteryear

He said long back, experts would know what treatment to give patients after they removed the sare. They also knew how to properly cut, he said.

“The procedure included either cutting the tip of the sare and apply traditional medicine or cutting it from the root. But now, because of a lack of expertise some just cut off indiscriminately whether 4 centimetres or longer. Long back they would be taught how to do it on different types of sare that include hadzi (female) and gono (male). Despite causing infertility, those with gono are also viewed as cheeky and hot heads,” he explained.

He said society should not blame women who go to discreetly have the sare cut.

“It is difficult for women to tell their husbands that they are going to have their sare cut. Men should be educated that women do not choose to have this. This is why they end up going alone in the absence of relatives yet going together helps keep families intact. Being part of the procedure reduces risk,” he added.

He said long back, it was done so openly and proper channels were followed.

“Long back, the wife’s and husband’s aunts would be told of the problem by the affected woman. The two aunts would then tell the husband that his wife would not be sexually active for two weeks because of some treatment. The husbands would understand. Hygiene was better for the woman as she had nothing to hide. Today’s women lie that they are menstruating,” he added.

He said today, communication lines and responsibilities of the extended family have been cut off and wrong methods and technologies are being used.

“You may find out that some churches also cut sare. The challenge is they are using the wrong methods because they failed to adopt what was done long back. Migration and inter marriages also eroded cultural values of many societies. Different people use their indigenous knowledge systems to treat diseases,” he said.

He said it is important for cultural health systems to be taken up by society and even in the constitution.

“The health sector can never fully treat diseases depending on stage. Some can be cured in a hospital but not traditionally. Others can be treated by traditional healers and not in a hospital. We support the referral system. If someone comes and we see the sare is too big and if I do not have medicine to stop haemorrhaging we urge our members to refer such people to health institutions,” he said.

He added that economic challenges have been the biggest pushback in the health delivery system.

“Sometimes you want to refer someone to a hospital but they do not have money. Some may go to a local clinic but are put on a waiting list sometimes three months. Because of desperation and family pressure, some women end up doing anything. Some will negotiate payments with a traditional healer and even pay a goat or chickens if they do not have money. Most women say they cannot do this in a health facility where payments are on a cash basis and also expensive,” he added.

He said there is need for more interactions between traditional and modern doctors so that they have one common position which promotes the referral systems.

Article 5 of the Maputo Protocol prohibits female genital mutilation and all forms of harmful cultural and social practices against women. The full text reads as follows:

“States Parties shall prohibit and condemn all forms of harmful practices which negatively affect the human rights of women and which are contrary to recognised international standards.

States Parties shall take all necessary legislative and other measures to eliminate such practices, including:

Creation of public awareness in all sectors of society regarding harmful practices through information, formal and informal education and outreach programmes;

Prohibition, through legislative measures backed by sanctions, of all forms of female genital mutilation, scarification, medicalisation and paramedicalisation of female genital mutilation and all other practices in order to eradicate them;

Provision of necessary support to victims of harmful practices through basic services such as health services, legal and judicial support, emotional and psychological counselling as well as vocational training to make them self-supporting;

Protection of women who are at risk of being subjected to harmful practices or all other forms of violence, abuse and intolerance.”

With high medical costs to have fibroids surgically removed in hospitals, many women might still take the cheeky traditional route of removing sare.

Feedback — Twitter: @RoselyneSachiti

Comments