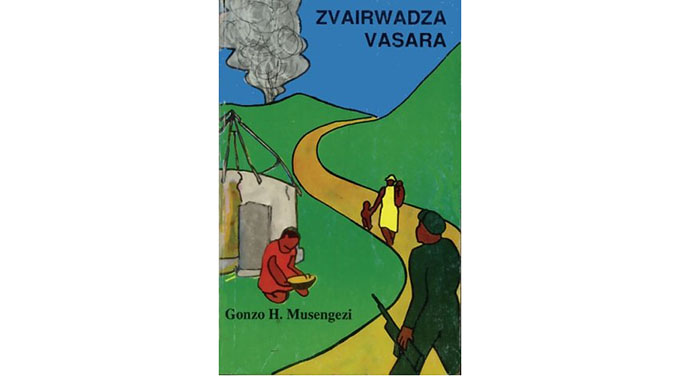

Bracing for the ‘Coming of the Dry Season’

Elliot Ziwira @The Book Store

Home is where the heart yearns for, where it grows fonder upon one’s realisation of its fulfilment of purpose; its charm, serenity and permanence. It is that special place where one wants to always be, devoid of worrisome feelings of betrayal, crestfallenness or disillusionment.

Such is the essence of home embraced by Zimunya and Hove in their poetry, which Charles Mungoshi sceptically questions and Dambudzo Marechera and Stanley Nyamfukudza masochistically frown at.

Charles Mungoshi in “Coming of the Dry Season” (1972) explores the nature of ideological and cultural conflict which somehow exposes the individual as he/she tries to locate himself/herself in the national discourse.

As in “Waiting for the Rain” (1975) Mungoshi uses his mastery of understatement, metaphor and irony to portray the stasis, malaise and paralysis of the family, community and nation. He effectively uses the metaphors of drought, waiting, rain, the setting sun, and the rolling world to purvey conflict at the personal, familial, communal and national platforms.

There is so much at stake as the new order threatens to subdue the old order, albeit blindly. The setting sun, which is symbolic of the old order, whose fortunes are on the decline, is juxtaposed with the new world which is on a roller-coaster, as symbolised by the metaphor of the rolling world. However, as these two conflicting worlds try to merge they encounter a void, which is metaphorically apt in the dry season of their toils. This is especially so because of ideological differences.

The cultural and ideological differences are not only a result of the generational gap that exists between parents and their children, but are also a culmination of colonial deprivation through Western education. Colonial education creates individuals who, because of lack of belonging, are alienated from their families and communities.

In their struggle for identity, these individuals fail to appreciate the traditional norms and values of their people and at the same time cannot be consumed into the alien culture of the imperialists, as they know little about it. They are desperate for change, yet they are not willing to be swept by the same tide which they envision.

In the story “The Mountain”, Chemai , who like the Old Man and Moab’s mother in “The Setting Sun and the Rolling World’’ and “Coming of the Dry Season” respectively, epitomises the old world with its roots firmly stuck in African traditional norms and values, finds himself at pains to defend his culture.

His friend Nharo, as his name may suggest, belongs, like Mari and Moab, to the new whirlwind sweeping across the African landscape. The daredevil and ebullient nature of his portrayal does not only point to youth, but is a culmination of Western education thrown down his throat wholesome. It is this that puts him at loggerheads with Chemai who epitomises untainted traditional norms.

Chemai’s steadfast take on the existence of the supernatural in determining destiny and a people’s way of life is scoffed at by the cantankerous and all knowing Nharo who clings to scantily discernible scientific explanations of phenomena; and the role of the individual in steering destiny.

However, although he is not convinced that white miners indeed abandoned their operations on the sacred mountain because of angered ancestral spirits who caused their mines to fill up with water, Nharo is scared of the goat that follows them. Because he falls short in his scientific explanations of its existence, he finds solace in the traditional herbs administered by his grandmother to cleanse him of evil spirits. This deceitful tendency of having one leg in and another one precariously hanging out is the bane of the African youths today which has a bearing on the socio-political environment that plays havoc on regeneration and progress.

The story aptly titled “The Setting Sun and the Rolling World” pits a father, Old Musoni, against his son Nhamo, who feels that there is nothing left for him in the land of his birth. Spurred by the desire to improve his condition, he tells his father that he wants to try his luck in the city. His father, on the other hand, is adamant that the only vent out of the quagmire is that offered by the land, which has always been the pride of his people.

Anchored by his traditional beliefs, the old man fails to realise that the sun is inevitably setting on his order which is fraught with inadequacies; and that myopia is a condition that reduces the individual to what is as determined by what had been against what should be. Yes, home is only home if it remains homely and offers humane conditions.

Yes, the land is where the roots are; and everything that one embarks on should be seen to have spiritual connectedness, it is true. However, although the land has a spiritual flair about it, it is no longer productive “as it has been overworked and gives nothing more, and the family is almost broken up”, and Nhamo observes. As a proponent of the rolling world Nhamo is conscious of the cultural and ideological dynamics at play but he is in a quandary as on what exactly he should do, even if he were to go to the city of his dreams.

Like Nharo, Moab and Mari, he believes that a static culture leads to paralysis, malaise and stasis at all platforms; familial, communal and national. However, the tragedy of it all is that these enlightened youths who are supposed to steer the nation to utopia lack ideological clarity to reach Nirvana.

Like Lucifer in “Waiting for the Rain”, Nhamo is alive to the fact that the land is overworked and has thus become barren, but his decision to leave for the bright lights of the city in a treasure hunt is as deceitful as it is ambitious.

The reason why the African clings to his barren existence has its roots in colonialism. Colonial subjugation is the culprit and not the land, yet Nhamo, like his fellow Western educated youths, besieges the city, not to question the status quo, but to protect it through labour. They find it easier to exile themselves for fodder, instead of working out a permanent solution for their people.

As a consequence, the colonial creations of the city which still exist, like the city woman and the bar that prey on them frustrate their efforts. When their people whose dreams keep on tottering to the horizon remind them of their lacks, they bemoan the claustrophobic inclinations of home and the family unit, forgetting that their enemy did not disappear with their disappearance to the city. The oppressive machinations at the centre of their suffering will stalk them no matter how much they run because they lack the capacity to discern friend from foe.

The African needs to know his enemies and create interfaces for compromise where ideological differences exist. Through interior monologue, Mungoshi depicts Old Musoni and Nhamo’s feelings as they question their existence in an oppressive world.

As a father and an African, the old man knows that nothing more is left to sustain the family as the land has become barren, yet at the same time he is aware that the city has no capacity to sustain his son either. As a humongous fish of prey the city will sap his energy, pound him in the stomach and eventually destroy him.

On the other hand, Nhamo reasons that coming back home is no different from returning to ruins but is lost on the fact that building starts with the laying of the first brick; and the city of his refugee broaches no such bricks.

Notwithstanding the fact that the sun is inevitably setting on the old world, it does not seem to shine on the new one either, as it sails radarlessly across tumultuous seas; gathering no moss.

Comments