Art theory and implication

Knowledge Mushohwe Art Zone

Formalist criticism of art is based upon an aesthetic assessment of artworks that gives priority to such formal elements as line, shape, and colour at the expense of representational elements involved with narrative, iconography and iconology.

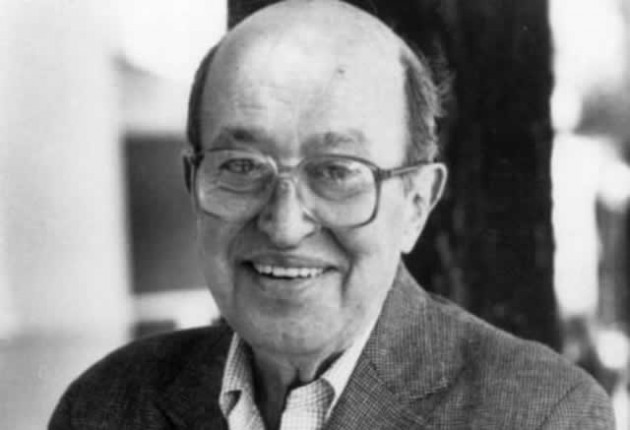

Theorist Clement Greenberg is most famous for writing an essay in 1939 named, “Avant-Garde and Kitsch”.

It was this essay and subsequent development of an art theory that gave Greenberg the reputation of being one of the foremost formalist critics of the mid-twentieth century with a strong belief that any analysis that searched for a deeper meaning of context or subject matter in abstract art went against the ethos of formal art theory.

After “Avant-Garde and Kitsch”, he began to develop his brand of formalist theory regarding innovative modern art and to advance the concept of art’s historical progress.

Clement Greenberg cannot and could not claim to be the godfather of this theory that came to be called formalist.

Eighteenth century German philosopher Immanuel Kant wrote his essay, “Critique of Judgement” way back in 1790 and Greenberg readily acknowledges that his ideas were inspired by the earlier work.

In fact, Greenberg wrote that because Kant “was the first to criticise the means itself of criticism, I conceive of Kant as the first real Modernist”.

Formalist criticism of art is based upon an aesthetic assessment of artworks that gives priority to such formal elements as line, shape, and colour at the expense of representational elements involved with narrative, iconography and iconology.

Greenberg says the artist that would typically pass the formalist test “tries in effect to imitate God by creating something valid solely on its own terms, in the way nature itself is valid, in the way a landscape — not its picture — is aesthetically valid; something given, increate, independent of meanings, similars or originals.”

In this way, Greenberg believed the artist would be able to show that the experience art provided could not be duplicated by kitsch, that it was unique and, therefore, a valuable experience in its own right akin to the experience of nature itself.

And while it is easy to say that Greenberg is no longer as relevant and that formalist theory and its doctrinaire condemnation of subjectivity, subject matter, relational composition, drawing, and spatiality are no longer regarded as dominant, it seems his formulations continue to be a powerful presence in one way or another.

Indeed, the formal qualities of an artwork are still and will forever remain relevant with respect to the art world.

But even from this first article in 1939, Greenberg’s formalism shows it grew out of his perception of the declining state of culture, particularly the emergence of impressionism and later art movements that in his view blurred the distinction between the art of mass culture, he called kitsch, and high art.

There were several critics and theorists during the era of Abstract Expressionism who adopted less formalist-based approaches to critiquing art.

These critics included Harold Rosenberg, Thomas Hess, and Leo Steinberg.

However, arguably no other critic challenged formalist art theory more than Robert Rosenblum.

A prolific critic, professor, and curator for most of his life, Rosenblum rose to prominence following the heyday of Abstract Expressionism and proceeded to redefine the history of modern art by stretching the historical boundaries of modernism to include eighteenth-century Baroque and Neo-Classicism.

By doing so, Rosenblum conveyed that all modern art forms were integrated into one large historical canon.

In fact, Greenberg’s rival with critic Rosenberg throughout the 1950s also continued to generate debate by maintaining that art appreciation was not only about formal qualities but other variables were equally important.

In the 1960s, however, Greenberg faced new attacks.

The art historian Leo Steinberg wrote an influential essay entitled “Other Criteria”, which questioned some of Greenberg’s judgements, and argued that there had to be other means of accounting for art other than by reference to the criteria of form.

And, “Kitsch” artists such as Jasper Johns and Andy Warhol, famed for creating abstracts and reproductions, made the formalism subject matter unavoidable in discussion of their art.

Greenberg’s formalism theory undoubtedly still has a role to play in today’s art because the elements of art such as line, form, colour, shape and texture used to evaluate creative compositions of the past continue to be used with just as much success today.

There is no doubt that these elements will continue to be used for centuries to come.

However, as the art world itself continues to evolve, so should the theories that may be applied to the fields of art.

When Claude Monet and his band of impressionists became prominent in the late 1800s with their artworks that defied the established principles of art, there was initial uproar led by other artists, art critics, curators and theorists.

But when the dust settled, “Impression Sunrise”, “Luncheon On the Grass” and other impressionist paintings of their time became iconic products that not only defined an era, but became pioneers of what was to be collectively known as Modernism and Post-Modernism.

Formalism is important in the understanding and critiquing of artworks, but it cannot work alone.

It is not just the formal qualities that foster a relationship between art and the viewers.

Rather, we “experience” art in its entirety and should not prioritise some variables over the others and call our verdict art criticism.

There is a lot more to art than formal qualities.

Comments