America is a poor puppeteer

David F. Schmitz Correspondent

Nuri al-Maliki, US-installed president in Iraq, is out. In Afghanistan, Hamid Karzai, another US puppet is on his way out. And it’s long past time for the United States to get out — of the puppet business, that is. The lesson of the last 10 years in Iraq and Afghanistan— and of the previous half-century or so in other countries America has dabbled in — is that we’re just not very good at propping up the right people in power. And we never will be.

Following Maliki’s decision to finally step down as Iraqi prime minister under pressure this week, giving way to Haider al-Abadi,a move the US supported,we should face the fact that the failures of both the Iraqi and Afghan leaders to establish stable regimes, or to provide security and end the internal fighting that has torn apart both nations, are only the latest sad chapters in this long history.

It’s no secret that since World War II, from Vietnam to Iran to Nicaragua, the US has played a role, overtly or covertly, in establishing many governments headed by hand-picked rulers.

The rationale usually has been based on oversimplified bipolar world views, outdated theories of modernisation and a paternalistic racism.

American policymakers, seeing non-Western Europeans as politically immature and particularly vulnerable to radical political ideas, believed that the US needed to establish and support proper rulers who would help their countries establish Western economic institutions and practices that would allow for the development of more “mature” societies.

Non-democratic methods and leaders became seen as necessary antidotes to radical political movements, social disorder and economic nationalism — even as the US convinced itself that it was promoting the rise of liberal democracies. More often than not, these efforts have failed miserably.

There are a variety of reasons for this. While the US has the power to overthrow governments and prop up leaders, it cannot install political legitimacy along with power.

But that lesson is never learned in Washington, and previous failures are dismissed as stemming from their shortcomings or our lack of will.

Take Vietnam. In 1954, in the wake of the French defeat, the US blocked the implementation of the Geneva Accords and helped install Ngo Dinh Diem as the leader of a new nation of South Vietnam.

The logic was that the French failed because they were a declining power tainted by colonialism, while the US had the resources, the will and the means to create a new country from scratch.

By 1963, tired of Diem’s corruption and incompetence, the Kennedy administration supported a coup that brought the military to power. The problem was not American policy or goals, officials believed, but Diem’s inability to carry out the necessary policies and prosecute the war against the communist-led National Liberation Front. But the various generals who held power in Saigon had no greater success despite ever-increasing numbers of American resources, advisers and troops. Once the US military shield was withdrawn, the shortcomings and lack of legitimacy of South Vietnam’s government led to its quick collapse under attack from North Vietnam and its guerrilla allies.

America often finds itself in a Catch-22 situation.

Leaders that Washington backs because they promise stability, opposition to communism or terrorism and support of American foreign and economic policies are invariably seen as the creation of the US. This undercuts their credibility, power and ability to rule. For years, the US saw the shah of Iran, installed in power in a 1953 coup, as an enormous success, his White Revolution a model of modernisation, and his country, in the words of President Jimmy Carter, as “an island of stability” in an area of turmoil, only to watch him driven into exile two years later.

The same pattern has held everywhere from South Vietnam to Nicaragua, and then to Afghanistan and Iraq today: As these regimes begin to wobble, they rely more on the United States for military support, financial assistance and guidance.

But the more aid they get from Washington, the more they look like puppets of a foreign power and begin to wobble even more.

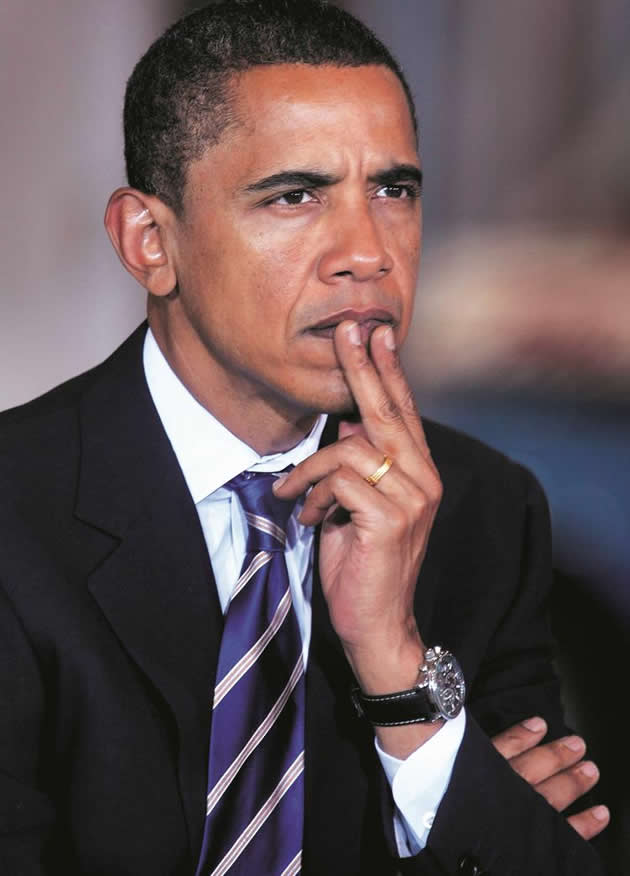

Now that Iraq has a new leader who is said to be an amiable technocrat without Maliki’s overriding partisan agenda, can the US escape its past as a poor puppeteer? Can Washington find a way to help Abadi rather than hinder him, empowering his government to take on the Islamic State without seeming to dictate its choices? The Obama administration says it supports Abadi because it wants to see the democratic process upheld, and there is nothing wrong with this position.

David F. Schmitz is a professor of History at Whitman College. – Politico

Comments