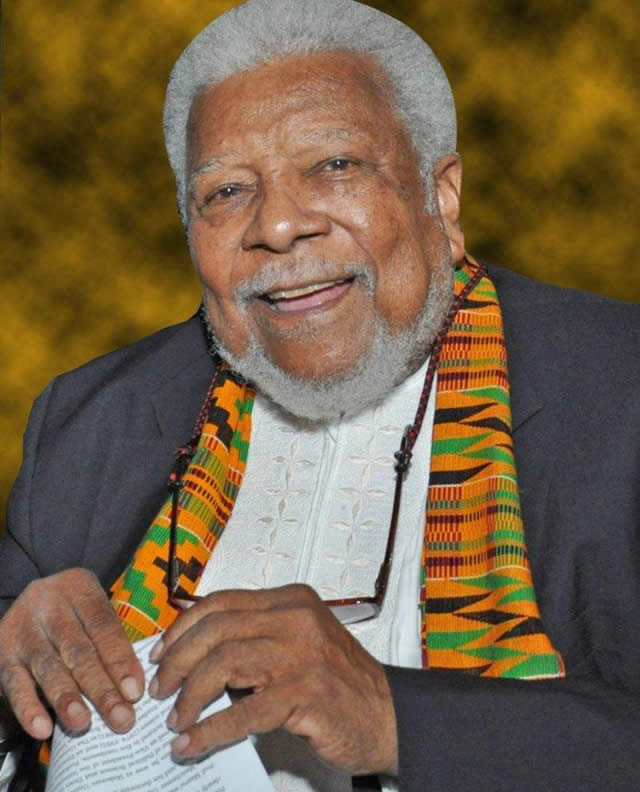

Ali Mazrui — Sunset for a giant

Bishop Matthew Kukah Correspondent

IN the passing of Professor Ali Mazrui, death’s cold hands have robbed Africa of one of its finest, razor- sharp intellectuals. Love him or hate him, nothing will take away his hugely visible footprints on the sands of time. It would not be an exaggeration to say the man was a genius of sorts. He had a way with words and he had a fascinating ability to weave a tapestry of prose around a complicated idea. He spoke in measured tones, possessed an enchanting ability to hold and almost taunt his audience into a trance. His eloquence was entertaining and educated. As the Irish would say, he had indeed kissed the blarney stone and been given the gift of the gab.

It would be silly to measure the man’s greatness by either those who agreed with him or the accolades he may have been denied. Had there been a Nobel Prize for Political Science, Professor Mazrui would have been the first African to earn it.

As the reader will soon see, I did not agree with all of Mazrui’s diagnoses, analyses or conclusions, but his gargantuan intellect was undeniable.

I cannot claim that I knew Mazrui well and I am not sure he would remember me, but we met on three or so occasions.

The first was almost an exercise in hero worship. I do not remember the year exactly, but I think it was at one of those moments when the University of Jos was enjoying some intellectual honeymoon as a centre for radical ideas.

I think Professor Elaigwu, perhaps Mazrui’s intellectual first son or cousin, may have had something to do with the visit. It coincided with the period in which the university’s political science department declared it would soon be able to boast General Gowon’s newly-minted PhD certificate as one of its claims to fame. But the general never took up the much advertised appointment.

When I read about the fact that one Professor Ali Mazrui was coming to deliver a lecture around 1985, I decided I would travel from Abuja to Jos to listen to him. My excitement was based on the way the topic was framed as I had never heard of Professor Mazrui himself. My friends in both Abuja and Jos seemed shocked that I would drive all the way just to attend a lecture. But I was not disappointed. I had never heard such eloquence in academia in Nigeria. The quality of his language and control of his subject was spellbinding.

In 1986, I resumed as a postgraduate student at the School of Oriental and African Studies in London. I had barely settled down when I learnt that Mazrui was coming to deliver a series of lectures over a four-week period at the Islamic Centre in Oxford. For the period of those four weeks, I travelled to Oxford to listen to him. As I did, I discovered that he was more or less restating the same arguments but in greater detail. I began to feel a sense of disquiet over the nature of his diagnosis. I was not sure whether it had anything to do with the idea that he was speaking on a Muslim platform and to a predominantly Muslim audience. I put pen to paper and wrote a critique of all the four lectures. They were all serialised in the now defunct African Guardian.

From that moment, I sensed something a bit troubling about the Mazrui narrative. I bought a copy of The African Condition, the book version of the prestigious Reith Lectures which he had delivered in 1979. With hindsight, it seemed that all of the ideas of his contained in the lectures were preparation for his highly controversial television series, The Africans: A Triple Heritage. Like probably every African in Europe, I sat by my television set to watch Mazrui’s excellent delivery. For me, the greatest part of the series was not so much its content, but the fact that an African had managed to place the continent before the world on the prestigious BBC and over a nine-week period!

Agreeing or disagreeing with Mazrui was a secondary concern.

Most of Mazrui’s critics have focused on this Triple Heritage series. And it would seem that it was indeed a turning point in his scholarship and life.

Many would argue that Mazrui’s bursts of Islamic fundamentalist hyperbole presented a distorted reading of Islam’s role and contributions in Africa. Professor Mazrui exhibited such a skewed reading of history that he seemed to have suffered bouts of extraordinary confusion in his reading of both Christian missionary activities and colonialism.

This confusion was manifested in his elision of missionary activities with colonialism and his dubious conclusion that the West was necessarily Christian, a fallacy that persists in the minds of many young Muslim scholars, even in northern Nigeria today. In my opinion, Professor Mazrui was unable to explain what harm missionary activities have done to Africans or the direct correlation between those endeavours and colonialism.

But even if for the sake of argument, such a nexus existed, in what way, shape or form did it hurt Africa? Is it an issue that missionary education displaced Arabic with English, that it left us a legacy of sound education (of which Professor Mazrui was himself a beneficiary) and a panoply of social services across the African continent? Mazrui’s pan-Arabic escapade meanwhile failed to exhume empirical evidence of what the legacy of the Arab exploitation of Africa was by contrast. Mazrui did hold up trade as a major contribution but seemed deliberately silent on the fate of African slaves and how they have vanished in the Arab world.

Slavery in the Middle East, which predated the transatlantic slave trade, has been understudied, and scholars have tended to live in denial of both its longevity and brutality. Right from the Abbasid period (750-1258), Arab rulers found slaves useful in the military and took advantage of their lack of roots as a means of ensuring absolute loyalty.

Later on, hundreds of thousands of young Africans served the Arab world as slaves and as descendants of slaves for over 300 years. As Africans, this is a theme that we must reflect upon as a reality and not borne out of bitterness of any sort. But we must ask the question, how and why is it that even after forceful or willing conversions to Islam in the Arab world, we have no trace of descendants of African slaves on the rungs of power in the Middle East?

In a lecture in Kano, Professor Mazrui made a claim that “Northern Nigeria was historically first in literacy among the peoples of Nigeria. Northern Nigeria was also the first in written literature”.

This statement had a ring of duplicity because how could Northern Nigeria, a large geographical area, become literate? Northern Nigeria is inhabited by hundreds of ethnic groups and is home to many cultures and so what kind of literacy was Mazrui talking about?

Was he speaking of Arabic as a language and, if so, is Arabic the native tongue of any of the peoples of northern Nigeria and if so, which? And how does Arabic literacy square with the civilisation that produced the Nok culture that spread between present day Plateau and Kaduna states or that produced the 8 000- year Dufuna canoe, discovered in present-day Yobe State?

However much we may have disagreed, it would be dishonest to take away from the man and the sheer volume of his contribution to knowledge. Mazrui’s ingenuity in forcing Africans to address the issues of their multi-layered identity in an intellectual manner must be considered a truly historic contribution to identity politics even beyond the shores of Africa. As I got to know his works more, I realised that somehow, Mazrui may have peaked in the early 80s and most of his works seemed to be a reiteration of the same theses. I was struck by the fact that after many years, when sharing a platform with Mazrui in the United States, his keynote address at a conference was a rehash of what I had heard in Jos, Oxford and read in subsequent writings several years before.

Professor Mazrui has been criticised for his reading of Nigeria’s history and his claims of expertise in the history and politics of the country. However, his inclination towards Islamic triumphalism would later so colour his narrative that most of his subsequent intellectual work found little appeal even among some of his earlier colleagues.

He gradually boxed himself into a corner and had to spend his time and energy seeking to clarify his now seemingly narrow view of the continent’s religious traditions in shaping African people.

Despite claiming to straddle other disciplines, the weaknesses in his scholarship lay in the fact that he was a political scientist and not a theologian or a historian. This was always an Achilles heel in his interpretations of religion.

The Triple Heritage series was a landmark in Mazrui’s scholarship but for the above reasons that I have mentioned, it exposed his prejudices and biases as he tried to rewrite aspects of Africa’s history.

The series laid the foundation for the embarrassing spat that emerged between the two titans of scholarship in Africa, Mazrui himself and Wole Soyinka. The rofo rofo and bare-knuckle fight between them showed a side of African scholars that it would be better for us to forget.

It would seem that for Mazrui, the Triple Heritage series was a notch higher than the Nobel Prize which Professor Soyinka has been awarded the same year. Soyinka argued that the series had undermined the major contributions of African traditional religions and cultures.

For all its worth, the open quarrel between two of the continent’s most powerful thinkers exposed a deep wound characterised by bile, prejudice and hate. The quarrel had no rhyme or rhythm. It defied the African values that the same scholars sought to extol. The gutter language that was spewed was as shocking as it was scurrilous. In one of the exchanges, Mazrui said to Soyinka: “You slapped me last evening. I am slapping you this afternoon.”

Professor Mazrui was a prophet denied honour in his own country of Kenya.

Perhaps he took an academic interest in Nigeria to compensate for this because despite his captivating intellect, the Kenyan authorities and even scholars seemed to despise or ignore him.

He was truly and naturally hurt. In despair, he stated that: “During the Kenyatta years, I could not be hired, but I was free to give lectures from time to time. But during most of the years of Moi, even the public lectures dried up. Can you imagine? My own country was seeing the documentary two decades after it had been shown by dozens of other countries and translated into several languages.”

It was also reported that when he turned 70 and was appointed to the honorific position of Chancellor of the University of Agriculture and Technology, no serious person turned up for the ceremony. The late Professor William Ochieng greeted the news with this cynical message: “For me, Mazrui is irrelevant to us. What puzzles me is that I cannot remember one single thing that Mazrui has written.”

At the height of their spat, Mazrui lamented that: “Professor Soyinka used to combine art with rudeness, but now, there is only rudeness.” But Mazrui would later call for peace in a manner that suggested that he could be a true gentleman.

In a letter he wrote to Soyinka, he stated: “I would like to return to the normality which once characterised our friendship. Younger Africans look up to us as intellectual elders. We have lately been disturbing their peace of mind with our quarrels. If you would stop abusing me in public, we could be friends and serve our people better.”

To paraphrase Mazrui, Africa needs to resurrect and reassert the intellectual warrior tradition. This is a tribute we can pay to Professor Mazrui. May God grant him a peaceful rest.

His grace Matthew Hassan Kukah is Bishop of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Sokoto, Northern Nigeria. This article is reproduced from New African.

Comments