Achebe, the civic mantle of the artist

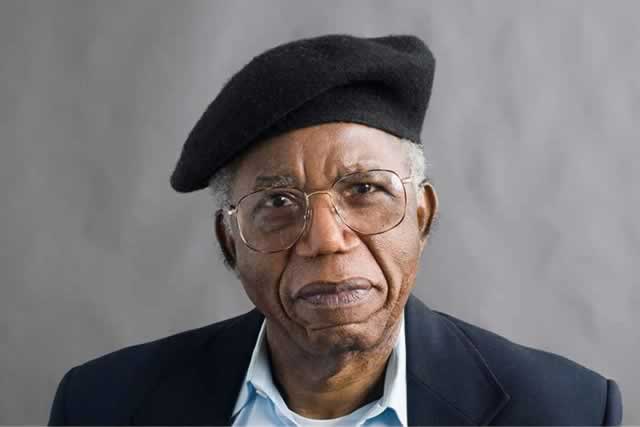

Chinua Achebe

Stanely Mushava Literature Today

Achebe argues that for him and Okigbo who died in service to the Biafran cause, art in Africa has not been distilled to an entity that can be separated from the strivings of its society.

Chinua Achebe’s last book, “There was a Country: A Personal History of Biafra,” provoked charges of political heresy.

The ethnic drift of the memoir polarised reception and reincarnated old hostilities, at least in the rhetorical domain.

Achebe was accused of reconstructing the history into a partisan frame, an inevitable charge given that he was relating events of the Nigerian Civil War from Biafran lenses.

Wole Soyinka said he wished his great contemporary had not written the book in the manner it came out.

Ironically, Achebe recounts how, as editor of a wartime publishing concern, he turned down a manuscript from a fellow Biafran insider because it buried history in a narcissistic blanket.

While his own book certainly rises above the charge of narcissism, it seems some critics may have equally turned it down for bundling together history with ethnocentric subjectivity.

Although the “personal” in the subtitle should furnish a disclaimer, critics are understandably taking issue with a “history” written by Achebe the Biafran envoy, rather than Achebe the Nigerian institution, decades after resolution of conflict.

Maybe, the merits of “There was a Country” in this respect are a story for another circle, one that can handle it with the benefit of compatriotic proximity.

But what verdict such a circle reaches, it will be amiss to push the book to the apocryphal section, outside the renowned Achebe canon.

There are issues worth of a more universal drift in Achebe’s memoir, chiefly his insight into the social function of the artist.

The autobiographical component of the book sheds light on the trailblasing role of Achebe and his contemporaries in selling the story of Africa to the world.

Some of the passages are reproduced from earlier works — the tribute chapter to Christopher Okgibo, for example, from “Hopes and Impediments.”

But they come together in an unprecedented autobiographical thread, from a childhood that oscillated between Igbo romances and a missionary upbringing to Goodluck Jonathan’s Nigeria.

We get to meet, not the grand personification of literary achievement we are accustomed to, but a young man coming to terms with his mission as a writer.

The humanising of the legend may be particularly important for young artistes who are yet to navigate the hinterland between obscurity and establishment.

Meeting a great writer as he scales the rungs from ambition to accomplishment may be of greater motivation than seeing him canonised, from a worm’s eye perspective.

In this regard, “There was a Country” is an important gift from a great writer, in the league of recent memoirs such as Ngugi waThiongo’s “In the House of the Interpreter.”

A common thread in the narratives is that talent flowers in any climate as a terrible beauty emerges from the hostile settings in which the artists found their mission.

In so far as it sheds insight into the civic setting of the writer, it is in the tradition of Soyinka’s “You Must Set Forth at Dawn.”

This stellar cast of pioneers has remained productive decades on, an example our own greats here will do well to build on.

“Most writers who are beginners, if they are honest with themselves, will admit that they are praying for a readership as they begin to write. But it should be the quality of the craft, not the audience, that should be the greatest motivating factor,” Achebe advises aspiring writers.

While Achebe is salutary of his generation, “early bards” like Amos Tutuola, Cyprian Ekwensi and the pre-colonial trove, he advocates dynamism rather than romantic hindsight.

Art, as an organic phenomenon rather than a distant abstract, must not be embalmed for veneration but regenerated for application.

Achebe cites the example of Igbo societies for whom he says art is dynamic rather than stationary.

He says the Igbo have no place for museums because each generation has to create its own version of life outside the template of its predecessors.

“So there’s no undue respect for what the last generation did, because if you do that too much it means that there is no need for me to do anything, because it’s already been done,” Achebe says.

But then defining art is a site of contest, template superimposing template, reality imitating rhetoric, fact imitating fiction, life imitating art.

Achebe’s template to end all templates resonates eloquently with Frantz Fanon’s revolutionary call: “Each generation must , out of relative obscurity, discover its mission, fulfil it, or betray it.”

In an age of post-nationalist abstract, Achebe argues that it is impossible to write anything in Africa, where mistakes of history already outline the setting, without a commitment, a message, or a protest.

He casts himself as a protest writer, right from start to finish, for even mild reconstruction of the African past, “Arrow of God” and “Things Fall Apart,” were protest against the misrepresentation that Africa was made in Berlin.

“Some of us decided to tackle the big subjects of the day — imperialism, slavery, independence, gender, racism, etc. And some did not. One could write about roses or the air or about love for all I cared; that was fine too. As for me, however, I chose the former,” Achebe recounts the formative years of modern African literature.

Writing back to the empire with its own instrument, the English language, required recasting with the rich lore of Africa traditions, to raise a new movement altogether.

The artist from the prejudiced end must take it upon himself to speak life into the literary tradition to convey his own story.

“I worry when somebody from one particular tradition stands up and says, ‘The novel is dead, the story is dead.’ I find this to be unfair, to put it mildly. You told your own story, and now you’re announcing the novel is dead. Well, I haven’t told mine yet,” Achebe says.

Achebe believes that only by being a participant observer in the civic strivings of their day can writers contribute meaningfully to the life of society and says those who remain spectators are only fit to write footnotes or a glossary when the event is over.

This does not sound entirely persuasive, especially when fitted into a sporting analogy. How does a player, single to one end, provide a comprehensive account of the action without narrowing down to subjectivity?

But that subjectivity seems to be the point, anyway: “The whole pattern of life demanded that one should protest, that you should put in a word for your history, your traditions, your religion, and so on,” Achebe says.

In his case, notable works such as “Beware, Soul Brother” and “Girls at War,” are set to the commitment ethic but then, also his allegedly partisan non-fiction.

Interestingly, an apparently innocent folktale, “How the Leopard Got its Claws,” is a nod to the Biafran war effort and an indictment on states perceived to be complicit in tyranny.

“In (Ali) Mazrui’s fiction (‘The Trial’) Christopher Okigbo finds himself charged with ‘the offence of putting society before art in his scale of values. . . No great artist has a right to carry patriotism to the extent of destroying his creative potential,” Achebe relates.

However, Achebe argues that for him and Okigbo who died in service to the Biafran cause, art in Africa has not been distilled to an entity that can be separated from the strivings of its society.

Ultimately, subjectivity is inevitable but must be informed by the climate of power. For Achebe, the artist’s moral obligation is not to ally oneself with power against the powerless.

Feedback: [email protected] <mailto:[email protected]>

Comments