A gripping herd-boy’s autobiography

Beaven Tapureta Bookshelf

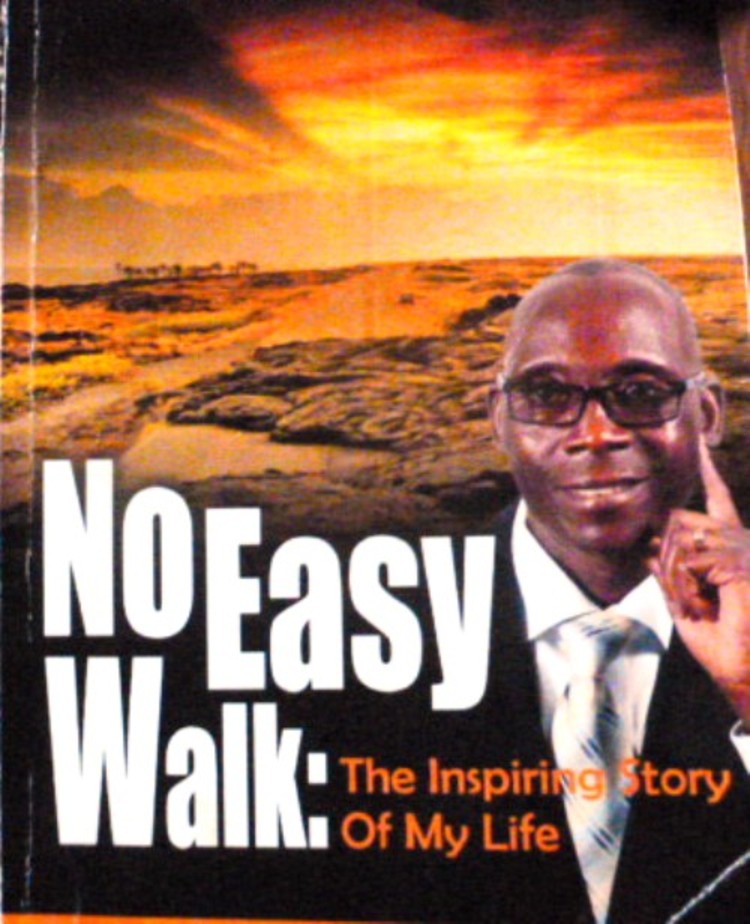

Dr Cainos Chingombe’s autobiography “No Easy Walk: The Inspiring Story of my Life” (2017, Canonbury Management Consultancy Services) will be an invaluable asset in the bookshelves of many Zimbabwean visionaries. If you are on the verge of giving up formal education because of old age or circumstances, then you must read “No Easy Walk”. The voice of Dr Chingombe narrating how he drew inspiration from challenges he faced in his life is quite engrossing.

It is a life story of a Buhera herd-boy who became a role model in the education sector, a gifted sportsman, a dedicated ambassador for God, humanitarian and a respected executive in the corporate world.

After reading the book, it stirred up thoughts why we do not have more of these gems of life stories from our elders in all fields.

Reading Zimbabwe, a continuously updating virtual archive (website) of Zimbabwean books (categorised in terms of genre) developed by writer and academic Tinashe Mushakavanhu, also confirms the scarcity of local autobiographies.

It is the future of Zimbabwe that we are denying the wisdom of yesteryear. Dr Chingombe has made an exemplary achievement.

His autobiography, stretching from his birth-day in 1956 to date, is a vivid chronological account of a cattle-herder who became a winner.

His story straddles culture, history, and the politics of Rhodesia. It gives a taste of the biased educational system of the colonial times.

Do some of our fortunate youths of today, who go to school or college well-shoed and well-uniformed, value education as highly as our elders did long time ago when they were young?

Do they know that during Dr Chingombe’s time, students would early in the morning first do house chores, work in the fields, later bath in the nearby river before hurrying barefoot to school?

The boys and girls in pre-independent Zimbabwe in their hearts they prized education.

This is the thematic power of the 220-paged “No Easy Walk”. Call it the individual “fight within” for self-discovery.

At some point the author, due to poverty, had to part with further primary education and took the hardest narrow road.

As a boy, he worked in neighbouring villages and farms. He met characters some generous and others cruel at heart. It was a wilderness. In one case he lived on wild fruits because his employer, a heartless woman, “fed” him with hunger for crimes unsaid.

He writes, “Two cruel months had come and gone without the promised salary. Hunger and lack had become my closest companions. Wild fruits had become my staple diet.”

A simple reader’s fragmentation of the book would put this phase as the “preparatory” stage in Dr Chingombe’s life.

As you flow with the tale, you travel memorable places, participate in happy and sad events and join the writer’s friends and relatives.

On the other hand, the language uses a storytelling style. The pulling in of other voices of friends and relatives into the autobiography also makes it a truthful account. But the dated colour photos that accompany the text are a bit blurred and should they have been clear, surely they too would have done magic to this life story.

Do you remember the popular Amato and Sons (Pvt) Ltd and its regular jingle on radio in the 70s and perhaps 80s? Before Independence, job seekers would gather near Amato, waiting for employers who came to pick the ones that qualified for their vacancies.

Dr Chingombe, a teenage straight from a cattle herding job in Mhondoro, says he lost a promising job after stammering in front of a white boss.

“I could not understand the English spoken. It annoyed him,” writes Dr Chingombe.

The humiliating incident would fire up his dream to be educated, a dream that also was one of the goals of the liberation struggle in which he took part young as he was.

Another historical place pictorially described is the Mbare Hostels, known in those days as Matererini.

The place exposed the intense racial discrimination in Rhodesia. It was “a place swamped with many poor black people”.

His brother, whom he had to stay with while in the city looking for employment, was the permitted occupant at this deplorable place.

To run away from inspectors, Dr. Chingombe says, “We would put up under Mukuvisi Bridge”.

There are moments of bliss, and of love, captured rivetingly but what’s extraordinary about this book is the passion for education Dr Chingombe displays and how he let others also feel the liberating power of formal education.

He says, near the end of the book, “From the shackles of poverty, I can, with full confidence, say that education was a potent tool that broke the yoke in my life.”

He is currently director of human capital at the Harare City Council where he also acts as Town Clerk on a revolving basis.

“No Easy Walk: The Inspirational Story of my Life” was edited by novelist and journalist Phillip Chidavaenzi and is set to be officially launched early next month in Harare.

Comments